|

The ChurchinHistory Information Centre www.churchinhistory.org

CROATIA 1941 - 1946 by

Part 1

INTRODUCTION From April 1941 until May 1945, a Croatian state existed as part of Hitler's Europe. It was the 'Nezavisna` Drzava Hrvatska' (The Independent State of Croatia), and referred to as the NDH. The Catholic Bishops and priests of Croatia have been accused of welcoming the establishment of this state, and the coming to power of Ante Pavelic's Ustasha Movement. It is alleged that this was led by dedicated Catholics aiming to make Croatia completely Catholic, and that as its population Included two million Orthodox Christians, they planned to kill or expel those who refused to convert. It is further alleged that the State and Church both issued edicts and laws to promote this aim. It is asserted that Ustasha detachments, led by Catholic priests, slaughtered hundreds of thousands of Orthodox men, women and children. It is said that the complicity of the Church is confirmed by the absence of any condemnations by the Catholic hierachy. Also, although aware of what was happening, the Pope welcomed Pavelic to Rome and considered him a "much maligned man". Most people reject such allegations as the ravings of bigots. But others, faced with documented evidence of atrocities, of instructions issued by bishops and statements made by priests, can come to accept them as partly true. Some may be even tempted to wonder whether the bishops were so pleased to be gaining converts that they closed their eyes to what was occurring. It is no possible to build-up a simple picture of wartime Yugoslavia. There were a multiplicity of ethnic, religious and political groupings, sub-divided into many factions led by local leaders and 'war lords'. Complex situations were continuously changing. In the southern and central areas, hundreds of villages and small towns were isolated from one another by mountains and gorges. Each community experienced its own distinctive history. We must not presume that events in one village, about which we have details, indicate the general pattern for the whole area. Due to poor communications, reports of incidents easily became distorted by rumours, lies and propaganda. In many instances these allegations and falsehoods can not be challenged because evidence has been destroyed. Villages often changed hands with periods of Serbian, Moslem, Croat, Partisan, German and Italian control. Each group carried out revenge killings, so obliterating clues of what had happened previously. The village of Berane in Montenegro changed hands forty-one times ((VI 228)). An extreme case, but one which illustrates the problem faced by historians.

CHAPTER I 1). A long history

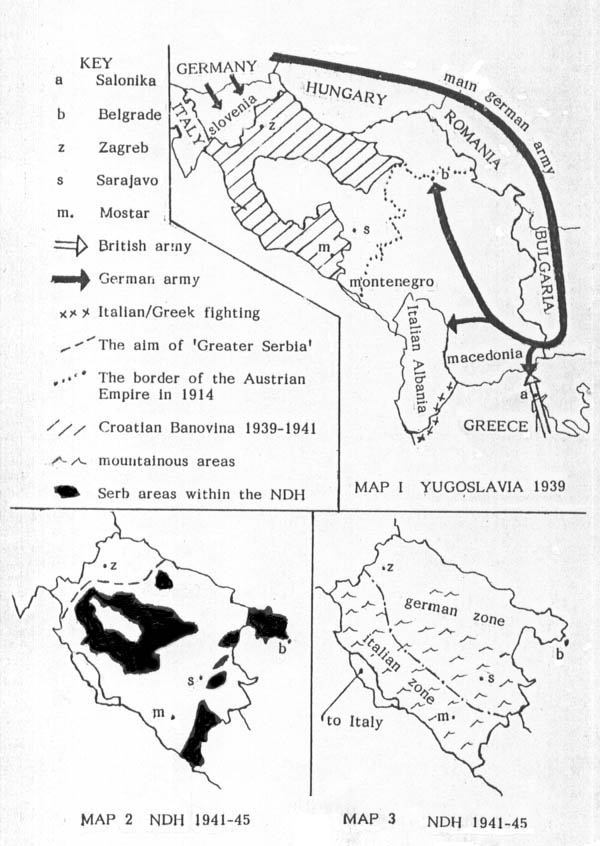

For over a thousand years, Slovenes, Serbs, Croats, Montenegrins and Macedonians have lived in the area which became Yugoslavia. But they have not been united by a common history. The Slovenes and Croats were converted to Catholic Christianity by missionaries from the West.. By the 9th century they had been incorporated into the culture of Western Europe and eventually became part of the Austrian Hapsburg Empire. The other peoples in the region (Serbs, Montenegrins and Macedonians) were Christianised from Constantinople and entered the culture of the Byzantium world. When the Patriarch of Constantinople (Byzantium) rejected. papal authority in 1054 and formed the Orthodox Church, these peoples followed his lead. After the fall of Constantinople in 1453 this mainly Orthodox region came under Turkish Moslem rule. Hundreds of years passed before these Orthodox populations were able, with Russian aid, to free themselves from a weakening Turkish Empire. Montenegro gained its independence in 1799, northern Serbia in 1830, the south in 1878 and by 1913 Macedonia was under Serbian rule. Also in 1913 the Austrians and Italians forced the Turks to withdraw from Albania ((EC 375)). Austria freed Bosnia in 1878 and the Congress of Berlin, convened by Russia, Germany and Austria, recognized Austria's right to its annexation ((NM 137)). This was carried out in 1908 ((NM 150)). The movement of refugees, following the many wars over the centuries, lead to the Serbian, Croatian and Moslem peoples becoming intermingled, especially In Bosnia. There was fredom of religion in the Empire, but Catholics were not permited to practice their religion in Serbia ((MTA 101)). In 1910 the Austrian Empire was 23% Austrian, 20% Hungarian, 13% Czech, 10% Polish, 8% Ruthenian, 6% Croat, 6% Romanian, 4% Slovak, 3% Slovene and 7% others including some Serbs. Hungarian demands for greater Independence had led to a Dualist Constitution, by which Austria and Hungary were self-governing equal states under the Emperor, who was responsible for foreign affairs. The administration of the smaller ethnic gimps was divided between these two states, with Croatia coming under Hungary and Bosnia under the Crown. (MAP 1). The Hungarians forced their language and culture onto the Croats. Although the Austrians and the Emperor deplored the harshness of this policy, they would not intervene for fear of causing a break-up of the Empire. In reaction to the Hungarian policy, some Croats demanded complete independence, but most hoped for local autonomy or statehood under the Monarchy. A small number wished Croatia to leave the Empire and unite with Serbia. Serbian nationalists demanded that those areas within the Empire with Serbian populations be incorporated within a 'Greater Serbia' (Map 2). But these communities were intermixed with non-Serbians who opposed this demand. By 1914 the Austrian Emperor was ageing and his son, Archduke Ferdinand, was preparing to succeed him. Ferdinand, alarmed at the growing strength of Hungary within the Empire, was thought to favour Croatian autonomy. Many Serbs feared that if autonomy was granted it would bring stability to Croatia and thereby end their hope of achieving a 'Greater Serbia'. On 28th June, 1914 Archduke Ferdinand and his wife were assassinated during a visit to Sarajevo in Bosnia. Evidence clearly pointed to Bosnian Serb terrorists as being guilty and also implicated Serbian military officers and government officials ((JT 9-10, NM 156)). In 1903 Serbian army officers had murdered the Serbian Royal family and the new king had rewarded the regicides with senior government positions. Britain and Holland severed diplomatic relations in protest ((EC 377)). In 1907 sixty of these regicides were still serving in the army, including the Commander in Chief. Another had become the Minister of War ((SSJ 55:75)). Colonel Apis had personally taken part in the killings, which included mutilating the bodies and throwing the king half alive from a window ((CM 199-207)). He now led the largest terrorist organisation in Bosnia and was also Chief of Intelligence on the Serbian government's General Staff ((EC 379)). The Serbian government assured the Austrians that it would control the terrorists who were using Serbia as a base. But most Austrians considered these assurances to be worthless. If assassins could kill the heir to the throne, and be protected from justice in Serbia, nobody in Bosnia could feel secure. When Serbia refused permission for Austrian detectives to visit Belgrade ((EC 399)), the Austrians invaded to depose the Serbian government. Russia went to Serbia's aid, and Germany to that of Austria. Europe was thereby plunged into 'The First World War'. Opponents of Austria asserted that Serbian sovereignty would be undermined if she agreed to Austria's demand and that Austria was using the assassinations as a pretext to expand her empire. 2). The end of the 1914-18 war As the conflict came to an end, the Austrian Empire was collapsing. Serbia wanted Bosnia and southern Croatia so as to form 'Greater Serbia'. Italy wanted Dalmatia, parts of Slovenia and western Croatia. If the Serbian and Italian claims were granted, the remaining area of Croatia, being non-viable, would have had to remain part of Hungary. In such a three-way division, the Croatian nation would have lost its identity. For many years Croatian intellectuals had been advocating a South Slav state. Slovenes, Serbs, Croats, Macedonians, Bulgarians and other peoples would express their cultural identities within a united federated Slavonic state. This idea gained the favour of the Great Powers (Britain, France and Italy). A revolutionary Croatian parliament declared independence and sent a delegation to Serbia. The delegation agreed to Croatia uniting with Serbia, Slovenia, Montenegro and Macedonia. Some Croats disputed the authority of the delegation to commit the Croats, without first referring back to their parliament. ((MTA 120)). The Croatian intellectuals were enthusiastic for the new state, but amongst the peasants there was a fear of Serbian domination. For most, the new state was at least preferable to Croatia being divided into three parts ((FT 32)). It has been asserted that the Catholic Church opposed the break-up of the Empire and the formation of Yugoslavia. It is true that some of the clergy admired the ethnic diversity of the Empire and its influence for peace. But Archbishop Strossmayer (1815-1905) of Djakovo had promoted the concept of a South Slav state ((SAB 20)), and had received Papal support ((CE 13:742)). Archbishop Bauer of Zagreb wrote articles supporting Strossmayer's ideals ((SAB 20)). After it was agreed to form a new state the newspaper 'Katolicki List', reflecting Bauer's views, wrote in November 1918:

Bauer recieved the Serbian Regent to Zagreb in 1919 ((RJW 34)) and the Conference of Bishops welcomed the new state ((SAB 60)). Ivan Saric, who became Archbishop of Sarajevo at this time, was a Croatian nationalist so did not share this enthusiasm ((RJW 34)). Carlo Galli, Italian Minister in Belgrade, reported to his superior, ". . . the Vatican is using its enormous moral and religious influence to bolster up a state, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, which is engaged in an underhanded campaign against us and our Interests. . . . the Croatian higher clergy have come out openly in favour of the Belgrade Government, and against Croatian nationalism." ((JFP 99)). 3). The Serbian Orthodox Church For centuries the Serbians were submerged in a Moslem world. As Islam makes little distinction between political and religious authority, and its life-style is so all embracing, its adherents tend to become a separate ethnic community. Under the Millet system, the Serbs were treated as an ethnic-religious community. The Serbian bishops were invested with semi-autonomous political authority and became the political and cultural leaders of the Serbs. So the Orthodox Church came to symbolize Serbian identity. For hundreds of years the Moslems and Serbs lived side by side. Although sharing the same valleys and towns, they were separated by religion, political administration, culture, dress, language, legal system, taxation, alphabets and script. The bishops preserved all these aspects of life so that Serbian national identity might survive. This fusion of race, culture and religion is not easy for a western European to fully comprehend. It is a phenomenon found along the periphery of the Islamic world. When the Catholic Spaniards emerged from Islamic rule in the 13th century, a similar fusion was present. Every Spaniard considered himself a Catholic and would die for 'his' Church even though he might be an atheist. It was the belief that Moslems would never be loyal to a Catholic royal family led to their expulsion from Spain in 1492. Similar situations may be seen in Armenia/Azerbaijan and Turkish/Greek Cyprus. Divisions within Nigeria, Chad and the Sudan are developing in a similar direction. The Sikh racial-religion was formed as an armed Hindu force resisting Islamic conquest. This fusion of race and religion was illustrated by Metropolitan Josif in his 1942 Easter Message:

In 1389 Milos Obilic had stabbed a Turkish army commander to death ((SSJ 45:47)). Prince Marko Kraljevitch was killed in a battle soon afterwards ((HWVT 98)). They both became legendary figures in Serbian history. In 1946 a new Serbian Patriarch pronounced:

Knowledge of this racial-religious fusion is fundamental in understanding the conflicts. Serbian nationalists, however irreligious, saw the Serbian Orthodox Church as the symbol and essence of Serbian life. For them conversion to, or apostasy from, the Serbian Church was not a purely religious event, but the most distinctive symbol of attempts to 'serbianise' or 'deserbianise'. Following the expulsion of the Turks in the 19th century, this Serbian racial-religious nationalism came face to face with a growing Croatian political nationalism. For many Serbs, Catholicism was identified with the Croatian ethnic and cultural community. Croats were seen as 'lost Serbs' who, when converted to Orthodoxy, would become Serbian. In this manner the Serbian Church came to be viewed by Croats as the greatest threat to Croatian life, freedom and nationhood. 4). Eastern Rite Catholics As the early Church spread from Palestine, two cities became centres for missionary endeavour Rome in the West, and Constantinople in the East. Although the two centres were united in the one Faith, the manner in which the Mass and sacraments were celebrated, the languages used, the laws enacted and the forms of spirituality practised, differed greatly. These differences came to be known as the Western (Latin rite) and the Eastern (Greek or Slavonic rites). These differencies are not important but, when in 1054 the Patriarch of Constantinople rejected the authority of the Holy See, the Eastern rite churches adheared to Constantinople. From time to time some Eastern rite dioceses have returned to Rome's authority, while retaining their rite (liturgical language, customs, laws and spirituality). They are known as 'Catholics of the Eastern (Greek or Slavonic) rite', but are frequently referred to by the Orthodox Churches as 'Uniates'. On visiting a Catholic Eastern rite church one may easily think it is an Orthodox one, as culturally they are not easily distinguishable from the Orthodox. It is sometimes asserted that Eastern rite churches are a halfway house to Catholicism. This is false. Eastern rite Catholics are as Catholic as the Pope himself, even though their liturgy and customs differ from those used in Western Europe. Over a period of 200 years, Ukrainian Eastern rite Catholics had fled from persecution by the Russian Tzars and the Communists. In 1941 there were about 22,000 living in the area which became the NDH ((BK 139-141)). The Eastern rite bishop of the eparchy (diocese) of Krizevic, located within the NDH, was responsible for all parishes of this rite in Yugoslavia ((CMA 450)). There has always been a danger that the small Eastern rite Catholics communities living in the West could become absorbed by the more numerous Latin rite. So the Church has made laws to discourage this occurring. Converts from Orthodoxy to Catholicism are required, as far as possible, to maintain their traditions by worshipping in an Eastern rite parish. 5). The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes It would be difficult to find a more variegated small state in the history of Europe. The new state formed in 1918 had a population of 12 million. It was 42% Serb, 25% Croat, 9% Slovene, 5% Macedonian, 4% German, 4% Hungarian, 4% Albanian and 2% Montenegrin. Fourteen languages were spoken and both the Cyrillic and Latin alphabets used. By religion, 47% were Orthodox, 40% Catholic, 11% Moslem, 1.5% Protestant, and 0.5% Jewish. Most Croats and Slovenes were Catholics, as were some of the Hungarians and Germans. With such diversity, sensitivity was required to ensure equality and cultural freedom, while developing a central, administration able to govern with adequate authority. The Serbs had long desired to bring all Serbs into a 'Greater Serbia', (Map 2) which would have been united in culture and religion. In such a kingdom small Croat, Moslem and other minorities would have had little effect on the Serbian ethos. But this new state, with its large numbers of Croats, Slovenes, Moslems and others, made it multi-ethnic. It was not the homogenous 'Greater Serbia' to which most Serbs aspired. Nikola Pasic, the Serbian leader, having lost the support of the Tzar in the 1917 Russian revolution, reluctantly agreed to the new larger state because of French and British pressure ((FT 32-33)). Moderate Serbs accepted the situation and were willing to live under some form of federalism. But the nationalist ones came to dominate and they imposed a centralist constitution. Also, instead of acting impartially, the Serbian king promoted serbianisation. The Serbian national day, which honoured the founder of the Serbian church, was instituted as the national day for everyone. The Serbian capital became the new capital, Croatian cultural societies were restricted and Serbian teachers appointed to Croatian schools. Although Catholics formed 40% of the population in 1921, she recieved only 7% of the government's subsidy for Churches ((SH 47)). In 1924 the government encouraged lapsed Catholics to make a final break with their church by morally and financially helping the 'Old Catholic Church' ((TB 29)). Privileges were offered to young Croats who joined the pro-Serbian Sokal youth association ((TB 11)). Of 670 senior officials in government departments 80% were Orthodox Serbs ((TB 14)). Of 117 Army generals, 115 were Orthodox and one a Catholic ((CF 268)). Croatian children were forced to write with Cyrillic charactors ((TB 11)). The aim was to make everyone Serbian. The ethnic struggle became one between centralism and federalism, with the Croatian Peasant Party acting as the mouthpiece of the Croats. On 19th June 1928 a Serbian member of Parliament, Punisa Racic, with suspected government support, shot five Croatian members from the rostrum of Parliament ((TB 9)). The Croatian leader, Stjepan Radic, and three others died. The remaining Croats withdrew from Parliament. Many Serbs hailed the assassin as a hero ((TB 9-10)). He received a light sentance in an open prison ((CC 14)) and allegedly given financial aid ((MB 120)). In 1929 king Alexander established a personal dictatorship, with General Zivkovic, veteran of the 1903 regicide, as Prime Minister ((FCL 111)). The name 'Yugoslavia' was adopted in October 1929 ((CC 13)). Political and cultural groups were banned and, following killings, the Serbian police came to be hated in the Croat areas. ((SH 120-122)). As the Orthodox Church was seen as a sign of Serbdom, the pressures on Catholics to convert were intensified. a. On 4th December 1929 Catholic and other independent youth groups were dissolved. Only the state controlled non-Catholic 'Sokols' were permitted ((SCB 179 and SSJ 53:29)). b. New Catholic schools were not allowed and efforts were made to close those already existing ((CF 268)). c. Falsifications and insults regarding the Catholic Church were incorporated into school textbooks ((CF 268)). d. Ukrainian refugees of the Catholic Eastern rite, from the Soviet Union, had their churches, at Prnjavor, Lisnja and Hrvacani, taken and Serbian Orthodox priests appointed ((CF 267)). e. Orthodox army officers were stationed in Croatian towns so as to encourage mixed marriages. These officers were bound by a confidential circular to marry in an Orthodox church and bring up all children as Serbian Orthodox ((CF 268)). Young Catholic women teachers were posted to Serbian villages with a similar aim ((CF 267, AHO 10)). f. Catholic settlers In Macedonia and Dalmatia were favoured by the state if they became Serbian Orthodox ((CF 267)). Areas were systematically colonised. As a result of one agrarian reform In a Catholic area, land was allocated to 6,394 Orthodox families and 286 Catholic ones ((CF 268)). h. Large imposing Byzantine style Orthodox churches were constructed in areas entirely Catholic so as to stress that the Serbian Church was the leading religion of the state ((CF 267)). i. Catholics, including children, were expected to honour St. Sava as the symbol of national unity ((RJW 37)). The Serbians claimed he had founded their Serbian church in the 13th century ((RJW 32)). Some authors have said that the expansion of the Catholic Church between the wars is a sign that She was free. It is true that churches were not closed, and that despite the discrimination new ones were opened. Also that there were flourishing Catholic organisations. But this was due to an expanding population leading to emigration from the countryside to the towns. Zagreb's population trebled between the wars, so eight new parishes had to be formed between 1935 and 1939 ((AHO 9)). Catholics were also becoming firmer in their Faith and therefore more willing to join church organisations. Orthodoxy is normally organised on a national basis and takes the name of the country into its title. Yet in June 1920 when the Orthodox peoples within Yugoslavia (Serbs, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Bulgarians and Romanians) were brought under one authority, the new church did not call itself the 'Yugoslav Orthodox Church'. It became the: 'Serbian Orthodox Church'. ((CF 273)). It was this central role of the Serbian Church in the campaign to serbianise all citizens of the new state, which made religion a major visible focus of conflict between the ethnic groups. 6. The Ustasha Following the 1928 assassination of Stjepan Radic, there were calls for complete Croatian Independence. But Vladko Macek, the new Croatian Peasant Party leader, continued to advocate autonomy and peaceful resistance to serbianisation ((VM 16)). Antun Starcevic founded the 'Party of Right' in 1861 and led it until his death in 1896 ((SH 31 and 106)). Josip Frank then became its leader and members became known as 'Frankovi' (Frankists). One of its few members of Parliament, Ante Pavelic, fled abroad to reconstitute the 'Party of Right' on 9th January 1929 ((FLC 4)). This was the day following the abolition of the Constitution and the establishment royal dictatorship ((SH 55)). He also formed a military organisation called the 'Ustasha' with himself as its Poglavnik (Leader). Mussolini, the dictator of Italy, aimed to annex Dalmatia, so welcomed an opportunity to destabilse Yugoslavia. He provided the Ustasha with money and a training camp near Bologna ((EP 22)) for 500-600 recruits ((SCA 3)). Unlike the Serbs, the Croats lacked a tradition of terrorism. So Pavelic visited Bulgaria and made common cause with the 'Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation' (IMRO), which agreed to provide the Ustasha with instructors in insurgency techniques ((SCA 3)). On the basis of this, and a speech made in Bulgaria, a Yugoslav Court sentenced Pavelic to death 'in absentia' ((SH 67)). The government depicted the Ustasha as fanatical terrorists who took bloodcurdling oaths. They saw themselves as 'freedom fighters', with their oath as the swearing of obedience to higher officers and of adherence to Ustasha principles. These principles, issued on 1st January 1933, asserted that Croats alone had the right to decide the future of their homeland, and their right to wage war for it. Many Ustasha were motivated by a patriotic love of Croatian history and culture, but for others it was one of hatred of the Serbs. Eugen Kvaternik, son of the man who would proclaim Croatian independence in 1941, gave voice to this when he said, "Anti-Serbian feeling was the essence of Ustasha doctrine, its 'raison d'etre' [reason for existence] and 'ceterum censeo' [central belief] ((MO 29)). The Movement didn't have a philosophical, political or economic programme beyond attaining Croatian independence. Religion was not mentioned. It was not fascist ((FCL 9)), but welcomed democrats, fascists, socialists, liberals, Catholics, Orthodox, Jews, Protestants and atheists as members or supporters. Some were of Serbian parentage and Orthodox by religion, but considered themselves Croatian by nationality ((MO 35-37)). Much support was received from the large Croatian emigrant populations in North and South America, who were aroused by reports of Serb oppression and terrorism in their homeland ((SH 55-105)). In Southwest Bosnia and the Serbian districts of Croatia, local Serb officials and police drove many Croats to emigrate. Ustasha members and supporters came mainly from these areas ((CBA 43)). The Ustasha were not without sympathy from democrats in the West. In its issue of 10th January 1931, following the Ustasha bombing of Serbian targets in Yugoslavia, the British liberal, 'Manchester Guardian' wrote:

In 1931 professor Albert Einstein and Dr. Heinrich Mann condemned the murder, with police connivance, of a world famous Croatian scientist by government terrorists. The 'International University Federation' called scholars to protest at the suppression of freedom in Yugoslavia ((SH 71-76)). On the 9th October 1934 Vlado Tchernozemski, a Macedonian desiring the independence of Macedonia, and working with the Ustasha, assassinated king Alexander during a state visit to France ((SCA 4)). Many Macedonians, Albanians and Croats saw Tchernozemski as a hero fighting tyranny((SG 224)). A French court sentenced the assassin to prison and Pavelic to death in his absence. But Italy refused to extradite Pavelic to Yugoslavia or France ((KK 4)). Eventually, due to international pressure and his growing friendship with Yugoslavia ((KK 4)), Mussolini detained Pavelic and closed the training camps. But groups continued to train in other parts of Europe and in South America ((MTA 126)). 7). The Concordat When king Alexander was assassinated in 1934, Archbishop Bauer was ill, so bishop Stepinac represented Catholics at the funeral ((SAB 28)). Masses were offered for the late king in all Catholic churches ((RJW 48)). As King Alexander's son Peter was a child, his uncle Prince Paul became Regent. Realising that Yugoslavia was tearing itself apart, he dismissed the Zivkovac government ((FCL 111)), appointed a moderate Serbian Prime Minister and released Vladco Mecek the Croatian leader from prison. A 1929 law had confirmed the position of the Serbian Orthodox church in Yugoslav life. Moslem rights were recognised in 1936 ((SAB 29)) and there was an agreement with the Jews ((RJW 36)). By 1937 Prince Paul's administration had negotiated a Concordat with the Holy See based on the Serbian one of 1914. Most of its articles were similar to those in Concordats agreed with other states, but one had a special relevance to Yugoslavia. Catholics would be permitted by Rome to use Glagolitic (Old Slavonic) in place of Latin in the liturgy ((CE 14:1089)). Catholic bishops including Archbishop Bauer had originally proposed this. ((RJW 34)). They hoped to bring Catholic and Orthodox worship closer and so promote Slavic and church unity. The Concordat was ratified in Rome and, during July 1937, passed by 168 votes to 128 in the Yugoslav parliament ((SAB 35)). But extremist Serbian nationalists saw it as an opportunity to inflame public opinion and overthrow the Regent's moderate ministers. The Holy Synod of the Orthodox Church proclaimed:

There were illegal demonstrations and in August the Synod excommunicated the nine ministers, including the Premier, who had promoted the Concordat ((KCA 2694)). The ministers considered the matter to be one of politics, not of faith or morals. They said the Synod had no power to condemn them unheard. Also to be valid the authorization of the Patriarch was required. He had just died and the office was vacant. The chief agitator was liable to excommunication himself because he was a priest who had contracted a civil marriage ((CMA 448)). The Concordat recognized the right of the Catholic Church to exercise her spiritual mission freely and publicly. The opposition claimed this would give her the right to convert Orthodox people to Catholicism. But the Orthodox were free to make converts amongst Catholics, so this was not a special privilege for the Catholic Church ((COMA 450)). Diocesan boundaries would be revised to accord with the state division of the country ((CE 14:1089)). The bishops would swear loyalty to the king and endeavour to maintain the loyalty of their priests ((SAB 32)). The Holy See would provide the name of proposed bishops to the government and, failing a reply within thirty days, would proceed with their appointment. The opposition said this gave the Holy See too much freedom of action ((CMA 450)). Articles guaranteed the freedom of Catholic bishops, priests and laity to communicate with the Holy See. Priests would be protected when exercising their functions; the confessional seal would be respected; it would be illegal for a lay person to dress as a priest, and a priest would not be arrested on a criminal charge without a previous report to his ecclesiastical superiors. Opponents claimed that intercourse by the Orthodox clergy with churches abroad was confined to the Supreme Head of the Orthodox Church and none of the other privileges were available to the Orthodox. But the reason was that they had never been requested. To meet these objections, the government said it was willing to grant similar rights to the Orthodox ((SAA 5, CMA 451-2)). Critics claimed the article regarding promises made before a mixed marriage interfered in home life. But the background needs explaining. The Patriarch had prohibited, except in very rare cases, mixed marriages in the Orthodox Church. The Catholic partner and any future children had to become Orthodox. The Catholic Church perform mixed marriages, with the non-Catholic left free to retain his or her own religion, providing a promise was made to have any children brought up as Catholics. Some Orthodox men had failed to honour this promise. This article strengthened the wife's position in law ((COMA 451-2)). Regarding education, teachers would be appointed in proportion to the religious affiliation at each school. Catholic children would not be forced to participate in Orthodox services, and Catholic schools would receive their fair proportion of government funding. It was also specified that school textbooks should not contain anything offensive to the religious sentiments of the scholars. History and other books had often shown grievous bias against the Catholic Church ((CMA 451)). Another article said that matters not included previously should be solved in accordance with Canon Law. Opponents claimed this constituted a relinquishment of the country's sovereign rights. But the final paragraph of' this article stated that if any difficulties arose, the Holy See and the government would meet in a friendly spirit to reach a satisfactory solution ((CMA 452)). The opposition also protested against compensation being paid for Catholic church lands taken for agrarian reform. Yet the government was already paying compensation for Orthodox church lands ((SAA 171)). The diocese of Zagreb had excluded priests from party politics for many years ((SAB 29)). The Holy See now agreed to the government's request to extend this ban to the whole country ((CMA 451)). The government said it would keep Orthodox priests out of party politics. This caused frantic opposition as such a law would affect personally many of those involved in the agitation. None of the thirty-eight articles encroached on the rights of the Orthodox Church or on those of any other religion ((CMA 452)). But on the 12th December the government bowed to the opposition and agreed not to ratify the Concordat ((CF 269)). The excommunications were lifted in February 1938 ((SCB 195)). Prince Paul exclaimed:

Some authors have asserted that the Pope then made a threat against Yugoslavia. But his words to a group of Cardinals on the 15th December were a lament not a threat:

Others have asserted that the Holy See made the signing of the Concordat a condition for the recognition of Yugoslavia. Yet recognition had been given and diplomatic relations established in 1919 ((SAA 5)). Most Croatian politicians were relieved when the Concordat was defeated. The Croatian Peasant Party was not based on Catholic social principles, but on nationalist and economic ones. In its early days most Catholic priests had opposed it and in 1911 the bishop of Zagreb had to ban pulpit attacks on it ((VM 51)). Its founder and its leader from 1905-1928, Stjepan Radic, claimed to support family life and often used the slogan: 'Faith in God and unity of the peasants' ((VM 47, 112-116)). Although, when dying, Stjepan Radic accepted the last rites of the Church, he had not been religious. In 1923 he had opposed the idea of a Concordat ((EP 31-32)), and the following year he allied the party with the Communist 'Peasants International'. While in Moscow he proclaimed, "We will march with Russia" ((SCA 20)). Vladko Macek, who succeeded him as party leader, was also not a practising Catholic having left his wife to marry another ((SAB 54-55)). These political leaders knew that if religious discrimination came to an end, demands for Croatian autonomy would receive less support. Also, the use of Glagolitic in the liturgy and the envisaged co-operation with the state in the selection of bishops, would strengthen the trend to a unitary Yugoslavia. Moderate Serbs, Croats and Slovenes would have a basis upon which to build a multi-ethnic and multi-religious united state. Croatian and Serbian nationalists could find themselves left on the sidelines of politics. Many of the Catholic bishops had also been worried ((RJW 49-50)). Archbishop Saric showed his opposition openly. He and others did not trust the Serbian leadership and feared the Concordat would lead to the Church supporting a Serb dominated state ((SAB 36)). 8). Croatian autonomy and the coup Hitler wanted a neutral and stable Yugoslavia on his southern border, when he invaded the Soviet Union ((JCS 8)). In 1939 half of Yugoslavia's trade was with Germany ((FCL 59)), so it was important for Hitler that these supplies were secure. So he opposed Ustasha activity aimed to destabilize Yugoslavia ((JCS 8-9)). Although protecting the Ustasha camps In Italy, Mussolini came to a secret understanding with Stojadinovic, the Yugoslav Prime Minister. They agreed that in the case of an armed conflict, Yugoslavia would allow Italy to occupy the Croatian areas of Dalmatia and Gorski Kotor, while Italy would assist in the creation of a 'Greater Serbia', which would include the Greek port of Salonika and part of Albania. When in 1940 this plan came to the knowledge of Prince Paul he dismissed Stojadinovic ((JCS 9-10)). In May 1940, Italy invaded Greece from her colony of Albania but, with British aid, the Greeks stopped their advance. Hitler saw the danger of British troops moving through Greece and Yugoslavia to attack him while the bulk of his army was in Russia. Also many of his factories were within bombing range of Yugoslavia. The need for unity, so as to avoid being drawn into a European war, made a Serb-Croat agreement urgent. In February 1939 Dragisa Cvetkovic became Prime Minister and Medek his deputy. The Serbs agreed to a Croatian autonomous Banovina. Although smaller than that claimed, the Croats accepted this compromise providing that the remainder of Bosnia was not absorbed into a Serbian Banovina ((FCL 91)). This 'Sporsiam' (understanding) was implemented on 25th August 1939. (Map 1). So Prince Paul, Cvetkovic and Mecek had laid the basis for national harmony. The Frankists (including the Ustasha), the Serbian extremists and the Communists opposed the Sporsiam ((VIM 196)). In 1941 the government signed a pact with Germany, promising to continue supplying her with raw materials and to prohibit British troops entering the country. In return, Hitler guaranteed Yugoslav neutrality. In the early spring of that year, Romania and Bulgaria had become Germany's allies, so Hitler would be able to send troops to fight the British in Greece without having to pass through Yugoslavia. The achievement of Croatian autonomy, and the German guarantee of the boundaries of Yugoslavia, appeared to doom the Ustasha cause. The treaty with Germany was signed on March 25th with the terms published the following day ((VM 213-6)). But on the 27th, Serbian extremists encouraged by Britain, carried out a coup. They proclaimed the seventeen year old prince as king. The motives are disputed, also how far British agents and money were involved ((JCS 13-15)). It appears the coup leaders feared there may have been secret clauses in the treaty and were opposed to the Croats gaining autonomy. Yet on April 4th the coup leaders promised to honour the treaty with Germany and respect the Croatian Banovina. If they were to be believed there seemed to be no reason for the coup, so few trusted the new rulers. Macek, fearing Hitler was beeing provoked into invading, agreed to become Vice President in the new government on condition everything would be done to avoid war. ((RP 31)). The slogan of the coup leaders had been "Better war than the pact" ((VM 230)) and the British radio celebrated the coup as an anti-German victory. Winston Churchill exclaimed in a broadcast: "Yugoslavia has found her soul". ((FCL 123)). In these circumstances Hitler felt the need to destroy the Yugoslav army in order to secure his supplies of raw materials, and protect his southern flank ((KK 13-15)), when he invaded the Soviet Union. 9). The Invasion and the NDH On 6th April 1941 the Germans invaded. The king and the coup leaders fled to Jerusalem ((RP 31)) then to London ((VM 230)). Cincar-Markovic, the former foreign minister and a victim of the coup, negotiated with the invaders. He signed the army surrender on the 17th ((FS 175)). In conquering twelve million people, the Germans lost 151 killed and 407 wounded or missing ((JT 74)). They took 200,000 prisoners ((FCL 130)). As soon as the Ministers reached London, they blamed the collapse on the Croats, accusing them of treachery and mutiny. At the same time, the Ustasha boasted that they had played a major part in driving the Serbs from Croatia. These politically motivated claims supported each other, but were not in accord with the military facts. On the 1st of March, Bulgaria had permitted a large German army to pass through and mass along the Greek frontier ((CB 25)). When Hitler decided to destroy Yugoslavia, this army turned to face west (MAP 1) and on April 6th twenty two divisions drove across southern Yugoslavia to link up with the Italians in Albania on the 11th ((SKP 107)). The Yugoslavs had not prepared this frontier for defence ((CB 31-32)) and the mainly Serbian troops, not wishing to fight ((JT 81)), offered little resistance ((JCS 16)). British troops landed at Salonika in Greece on the 7th ((CB 20)) but were too late to assist Yugoslavia. The Germans raced northwards to Belgrade which, after minimum resistance, fell on the 13th. ((CB 39, SKP 107)). Croatian troops were not involved in this collapse. Meanwhile, a smaller force of ten divisions had advanced across the northern border from Austria. As 161 generals out of 165 were Serbs ((FCL 71)), the Croats viewed the army as being Serbian. Although some Croatian units did delay the German advance ((VM 228)), most of the conscripted Croats were not willing to die for Yugoslavia. A regiment at Bjelovar refused to leave barracks ((JT 79)) and another disarmed its Serbian officers ((VM 228)). A Croat colonel moved troops out of Zagreb to enable Slavko Kvaternik, on behalf of Pavelic, to proclaim Croatian independence over the radio. This occurred on April 10th, a few hours before the unopposed arrival of German troops. ((JT 70)). The proclamation produced a Croatian uprising, with most of those spontaneously taking part not being Ustasha members or sympathizers. Although German broadcasts had urged the minorities not to fight for their Serbian masters, they had not promised independence for Croatia ((JCS l8-19)). Hitler proposed that Croatia be administered by Hungary. But Hungary refused and gave speedy recognition to the new Croatian state. Italy also gave recognition ((JCS 27-30)). Seeing the attitude of his allies and the Croatian enthusiasm for independence, Hitler recognised Croatia on April 12th, but was not concerned as to whether Kvaternik or Pavelic became head of the state ((JCS 21-25)). During the night of 14/15th, Ante Pavelic with a few hundred Ustasha supporters arrived in Zagreb from Italy and, with Hitler's permission, took over control from Kvaternik. So two aspects of these events are clear: A. Ustasha actions had minimal effect on the military collapse of Yugoslavia, but did lead to Hitler recognising Croatia as a separate state. B. The Croats had gained a form of independence but had not chosen their government. Hitler left details of the extent of the new state to be decided by Mussolini. This was set out on May 18th ((SH 174)) and came into effect two days later. It was to be known as `Nezavisna Drzava Hrvataka`, or as abrieviated: NDH. It was formed from Croatia and Bosnia. Italy took small areas along the Dalmation coast although inhabited by Croats. In Bosnia the Serbs were 44%. to 31% Moslems and 22% Croats ((BK 174)). The Moslem attitude was therefore crucial. During the 1914-18 war the Moslems had supported the Empire against the Serbs ((NM 159)) and afterwards co-operated with the Croats to fight Serbian pressures for centralisation ((NM 164)). In 1924 all but one of the 24 Moslem members of parliament identified themselves as Croat of the Moslem religion, although their leader considered himself to be a Yugoslav ((NM 165-6)). Svetozar Pribicevic, a Serbian leader, accepted that the Bosnian Moslems identified themselves with the Croats ((FT 114)). But this identification was political and national rather than ethnic. The new Ustasha government didn't consider the NDH to be a Catholic state. From the earliest days it was seen as a nation of two religions: Catholic and Moslem, with the recognition of Protestantism. Pavelic declared the NDH to be a country of Catholics and Moslems. The Moslems had seats in the Sabor (Parliament), when established in 1942. In general they accepted the NDH ((SKP 111)) and aligned themselves with the Croats in the wartime fighting. Moslems were not represented in the exiled Yugoslav government in London ((NM 187)). As a whole, the NDH had about 3,360,000 Catholic Croats (51%), 870,000 Moslems (13%), 1,970,000 Orthodox Serbs (30%), 120,000 Germans (2%) and 290,000 others who were mainly Catholic ((BK 173-4)). Books frequently give the Moslem population as 750,000 but this appears to be too low. When the Germans invaded, Macek urged the Croats to resist ((VM 227)), but soon realised that Croatia's future would depend on world events. If Germany became the master of Europe, the NDH could be the means of preserving some degree of Croatian Independence. If Germany was defeated and Yugoslavia restored, the Croats would have to insist on the re-establishment of the Croatian Banovina. In pursuit of this view he appealed over the radio for the people to accept the new state ((VM 229)). At the same time he expected the Yugoslav government in London to guarantee the future autonomy of Croatia ((RP 31)). As Macek considered the real master of the NDH to be the German ambassador Von Kasche ((VM 240)), he withdrew from politics ((SCA 5)).

10). Descent into chaos Shortly after the Germans invaded, and before their troops had reached southwestern Bosnia, Croatian refugees were arriving in Mostar. On 13th, 14th and 15th of April, Serbians had attacked the villages surrounding Capljina. Eightyfive houses in the villages of Illici and Cim, two kilometres from Mostar, had been burnt down and many of their inhabitants killed ((TB 34-35)). In the north, the lightly armed Civil Guard of the Peasent Party, which was permitted by the Banovina agreement ((JT 25)), toured Serbian areas without incident ((VM 231)). But soon afterwards, Croatian refugees were arriving in Zagreb reporting Serbian attacks in the Glina area. Some of these refugees eager to defend their homes, or to wreak revenge, joined the Ustasha militia units being formed ((VM 231)). As the Germans would not permit a Croatian army, order had to be maintained by these hastily recruited, untrained, indisciplined Ustasha units. They included terrorists recently returned from abroad and young recruits lusting for revenge. On 1st May Communist symbols appeared throughout Glina to the south of Zagreb. On 11th May a group of Ustasha arrived and killed 373 Serbian men. On 29th August they returned and, by using the ruse that the Serbs were to be converted to Catholicism, persuaded 700 Serbian men from nearby villages to enter Glina's Orthodox church. The Serbs were made to shout: "Long live the Leader". [Pavelic] before all were slaughtered ((SSJ 63: 78-80)). Second Lieutenant Rolf, commander of these Ustasha, also arrested the women of Glina most of whom had outwardly become Catholics. When Fr. Zuzek, the Catholic village priest, realised Rolf intended to kill them he phoned Archbishop Stepinac. He used the phone of the moderate Ustasha officer in charge of the district and spoke in Latin so Rolf's man in the Post Office would not be able to understand him. Three hours later Rolf, under orders from Pavelic and in an angry mood, said Fr. Zuzek could release the Catholic women. A pupil of Zuzek released the Orthodox women and the priest hid them until he could send them from the village ((RP 404-7)). During these spring months, Colonel Draza Mihailovic of the Yugoslav army began to build small mobile units with which to prevent the Germans and Croats controlling the mountainous areas. They became known as 'Chetniks', the traditional name for Serbian armed bands of nationalists. Throughout Bosnia and parts of Croatia, Moslems, Croats and Serbs established units to protect their villages. In many places these groups proclaimed themselves as Croatian 'Ustasha' or Serbian 'Chetniks'. Not being satisfied with a defensive role, some launched attacks on neighbouring villages. The more responsible Ustasha and Chetniks called the violent ones: 'Natasha' Wild Ustasha, or 'Divlji Celnici' Wild Chetniks ((HT April 1992:7-8)). In many areas responsible Ustasha and Chetnik leaders had little or no control. So many fanatical and criminal gangs, calling themselves 'Ustasha' or 'Chetnik', were not under the authority of Pavelic or Mihajlovic. At Hrvatski Blagaj two Ustasha tribunals decided not to execute some local Serbs, but fanatics still killed 400 in one night ((SSJ 51: 99)). Criminal elements took advantage of the breakdown in law and order and often used the Ustasha and Chetnik labels to cover their crimes ((HT April 1992:7-8)). The situation also provided the mentally disturbed with opportunities to act without restraint. Reports tell of people being killed with knives and thrown over cliffs. Exaggerated rumours spread by the Serbs, and harangues by high-ranking Ustasha leaders in May and June, made things worse ((MO 30)). On May 20th, the Italian army handed administration of the western areas of Bosnia to the Croats. This was in accord with the agreement of 18th May fixing the borders of the NDH. When local Serbian officials refused to serve under the NDH authorities, Moslems were frequently appointed as village administrators ((JT 132-133)). This led to further incidents and these escalated in intensity. On 3rd June there was a widespread but unorganised Serbian uprising. This was quelled in most areas by the middle of July ((JT 133)). In Krajina and Lika the Serbs took up arms, 'as a people' ((MD 206)), and were suppressed as a people. The systematic killing of Serbs was reported from this area of Croatia and from northwestern Bosnia ((VM 234)). In the south, at Surmasci, close to the Croat villages destroyed in April, 559 Serbian women and children were thrown into a pit on 6th August ((EP 103)). In the village of Krnjeusa the Serbs massacred 800 Croats ((SAA 29-30)). Milovan Dijas, a Communist leader, travelling from Belgrade to Montenegro in the middle of July, later wrote that there were no Croatian border guards when his train entered the NDH from Serbia and none when it left to enter Montenegro. Even in the main Bosnian town of Sarajevo, he saw two young Ustasha only ((MD 10)). This report confirms that the whole region was out of the control of the national leaders. Serbs boarding the train at Mostar told Dijas of the Turks [i.e. Moslems] driving men, women, young and old to a ravine and striking them down with clubs ((MD 9-11)). They also said many Ustasha had been killed in a nearby village. Serbs tended to call all Croats and Moslems 'Ustasha', so the killed could have been unarmed women and children. Similarly, the 'Chetniks' claimed to have been killed by the Croats and Moslems, could have been Serb women and children. We read of Catholic Fr. John Kranjac's barbecued body being delivered to his village of Nunich ((MR 75)), and of an Orthodox bishop and priest being blinded and having their noses and ears cut off before a fire was lit on their chests ((EP 73)). We hear of Catholic Fr. Barisisch having his ears, arms and legs amputated before being thrown into his burning church at Krnjeusa ((MR 75)). We hear of Serbs at Stikade being buried alive ((AM 84)). It is said that Catholic curate Mladina was crucified and left to hang for three days at Gospodnetic impaled on a picket while still alive and roasted by fire ((SH 185)). We read, "The last group of Serbs were burned together with the church and its priest, Bogdan Opacic". ((EP 105)). The Italians recruited Chetnik bands to fight the Ustasha who had been attacking the Italians. When at Prozor a band of these Chetniks killed over 1,000 Croat women, children and old men, the Italians discharged those who were guilty ((TB 36, JT 233)). Pages could be written of these true or alleged atrocities committed by both sides. It is difficult for a person in the West to judge which stories are true, false or exaggerated. Chaos was not confined to NDH territory. In Montenegro there was fierce fighting between Albanians and the Montenegrin Serbs as well as between Moslems and Serbs ((MD 22, 40-41)). In Kosavo the Albanians attacked the Serbs in revenge for pre-war brutality ((HT April 1992: 7-8)). There were spontaneous expressions of hatred throughout much of former Yugoslavia, which escalated into acts of savagery and revenge on all sides by roving bands of thugs. The great majority of Serbs, Croats and Moslems were not responsible for the acts of these mainly young killers. Nor should religious motivations be ascribed to such hate filled bestialities. In the absence of local administrators, village priests came to be seen as leaders and symbols of their ethnic communities and so suffered the full hatred of these blood-crazed gangs. 11). Ustasha rule The popularity of Croatia gaining its independence led most Croats to continue their civic duties and others to offer their services. Many had been Peasant Party members, others non-political. Those Peasant Party leaders who opposed the new government were arrested ((VM 233)). The Ustasha, as the armed expression of the Party of Right, was a military organisation rather than a political party ((MD 199)). It had about 40,000 supporters, almost exclusively from the South Western area of Bosnia known as Herzegovina ((CBA 43)). Being a poorly educated area, few had administrative abilities. The Germans were not pleased with the chaos during the summer of 1941, as they had hoped to secure a peaceful flow of raw materials to Germany. But spontaneous fighting between the communities was not the only cause of chaos. The NDH government was determined to extinguish all Serbian power and influence within the new state. Cyrillic lettering was forbidden and Serbian schools closed ((SAA 22)). Two thirds of the Serbian clergy were deported to Serbia. On 4th June the NDH and Germans agreed to establish the 'Panovu' organisation to deport the anti-NDH Serbs. This was formed on the 24th of June and deportations commenced in July ((SAB 70-71)). The fear, engendered by the speeches of Ustasha leaders, the terror gangs and the lack of condemnations by the government, caused a great exodus. Those staying had to show their loyalty to Croatia by leaving the Serbian Church. This would ensure that their children would not be brought up with Serbian loyalties. Serbs could transfer to Catholicism (Eastern or Western rite), Protestantism or Islam ((EP 121)). Serbia became so flooded with refugees that the Germans in late September ordered the deportations to cease. By then 120,000 had arrived in Serbia ((JT 106)). It was in these first months, when the government was without an army, that the 'Wild Ustasha' bands operated. In July the Germans permitted a conscripted army known as the Domobran (GAO 39)), but as many were employed guarding German supply lines, the government still had few troops with which to maintain law and order. But before the summer was over most of the wild `Natasha` bands (The wild ones or 'Upstarts'), had been disbanded ((JT 107)). On 30th August 1941 Pavelic ordered the execution of Croats guilty of atrocities ((HMO 58)). Croatian resentment at the Italian aquisition of parts of the Dalmatian coast continued to provoke clashes. By August 1941 the Italians were planning the Chetnik attacks on the Croats and Communists ((JT 213)). The Italians encouraged the Chetniks in the ethnic cleansing of Croats from areas near the new Italian possessions ((FM 177)). In return they provided safe shelter for the Chetniks when the Croats fought back ((SH 177-8)). In September the Italians reoccupied large areas of Bosnia, claiming they were protecting the Serbs from Croat attacks ((SKP 112)). Pavelic came under great pressure to establish law, order and justice. This came from the Germans ((MTA 157)), the Italians, Stepinac in many letters, and Croat public opinion. Condemnations came from the Franciscans in June 1941 ((OFM Doc.1)), the Moslems on 13th November ((CF 287-8)), the conference of Catholic bishops in mid-November ((SSJ 5:38-47)) and the Protestants on 19th November ((CF 286)). In September the Germans asked Malek to replace Pavelic. Although he refused, Pavelic saw the danger and, imprisoned Malek in Jasenovac camp ((VM 240)). Pavelic's need to gain wider Croat support and to conciliate the Serbs, enabled the liberal and Catholic elements within the Ustasha to gain greater influence. In October 1941, Milan Budek, a vocal extremist, lost his government position when appointed as minister to Berlin ((FO 48919)). In February 1942 a Sabor (parliament) was opened, composed of non-Ustasha elected prior to the war as well as of Ustasha appointees. The formation of a Croatian Orthodox Church was announced and attempts to expel or 'convert' Serbs came to an end. It was some time, however, before all Ustasha bands conformed to the new policy. By 1942, the Partisans and Chetniks were fighting one another. Both expected Germany to lose the war, and knew that whichever was then superior would either impose Communism or re-establish the monarchy. By April many Chetnik units had made truces with the Germans and the NDH ((FM 177)). Later that year they started to co-operate with NDH troops to fight the Communists ((JT 216)). The Communists wished to concentrate on destroying the Chetniks so, in late 1942 and early 1943, they also asked the Germans for a truce, but Hitler refused ((JT 244-5)). As Germany's main interest in the NDH was as a source of raw materials, they pressed for peace ((MTA 160)). In October 1942 two Ustasha hard-liners, opponents of reconciliation with the Serbs and the formation of the Croatian Orthodox Church, were dismissed from the government. General Slavko Kvaternik, Commander of the armed forces went abroad. Eugen, his son, was dismissed as head of the Security Services, which were then placed under the Ministry of the Interior ((IO 21-22)). By 1943 some Chetniks had recognised the NDH and were being supplied with weapons and their pay sent to their relatives ((JT 227)). On 3rd January 1943, German, Italian, Chetnik and Ustasha officers met in Rome ((MD 215)) and seventeen days later they co-operated in a big offensive to destroy the Communists ((MD 227, FM 203)). These Chetniks were still loyal to the Yugoslav London government, so this illustrates how complicated events could become. Regardless of agreements and truces, violence between the communities and political factions continued throughout the war because each valley and village had its own war-lord and local history. The move towards NDH moderation had commenced with Budek's dismissal in October 1941, and had continued with the dismissal of the two Kvaterniks in October 1942 ((IO 21-22)). In September 1943 Nikola Mandic, not an Ustasha, became Prime Minister, and he brought other non-Ustasha into his cabinet ((IO 23-24)). In the early part of the war, Hitler had permitted a degree of independence to Vichy France, Denmark, Slovakia and Serbia. But as the war progressed Neo-Nazi politicians gained greater power that led to more extreme and brutal policies. In Croatia, extremism was exhibited at the beginning with the resulting chaos leading to more moderate policies. 12). The Serbian Bishops Gavrilo Dozitch, Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church, was arrested on 23rd April 1941. It is sometimes implied that this was an act of Croatian Catholic religious persecution. But the facts tell a different story. The pact with Germany to assure Yugoslav neutrality was signed on 25th March 1941. The Patriarch, in letters to Prince Paul and government ministers, had vigorously warned them with all the authority of the Church not to sign. On the 25th he broadcast an impassioned radio appeal on behalf of the Serbian Church. He called on all Serbs to remain true to the ideals and traditions of their church and nation ((SAA 7)). Within two days army officers had overthrown the government in what was seen as an anti-German coup. So when the German army found the Patriarch in the Montenegrin monastry of Ostrog, they arrested him as a political enemy. Following rough handling he was kept in monasteries till near the end of the war, when he was taken to Germany, being freed there in 1945 ((SAA 10-18)). Neither the Croats, the NDH government, the Ustasha nor the Catholic Church had anything to do with these German actions. Montenegro was not even part of the NDH. In May 1941 the eight Serbian bishops (one diocese was vacant) and their priests were ordered to leave as part of the government's policy of ending all Serbian influence in the NDH. In Croatian eyes these clergy had led the twenty- year war on Croatian culture and identity and had urged the coup that had brought to power men opposed to Croatian autonomy. These bishops could now be expected to lead resistance to the new Croatian state. While the government didn't order maltreatment, the 'Wild Ustasha' took brutish action. Four bishops fled to Serbia, three were murdered and one died of natural causes in June ((SAA 10-15)). The Catholic Church was not involved in any way with the issuing of the expulsion order or in the violent actions of the Ustasha thugs. It is sometimes asserted that the bishops of Banja Luka and Zagreb were especially badly treated because they had opposed the 1937 Concordat. There is not the slightest evidence for this. The assertion is made so as to portray the thugs as acting from a religious motive. All the Serbian bishops had opposed the Concordat, as had the Ustasha. The Italians arrested the Serbian bishops in their zone, and in Albania, because they were considered to be political enemies ((SAA 24)). 13). The Croatian Eastern Orthodox Church On arriving in Serbia, following his expulsion from Macedonia, Metropolitan Josif of Skopje was elected by the Serbian Church Synod to deputise for Patriarch Gavril. He made contact with Gavril and was instructed by him to normalize Orthodox matters in the new Croatian state ((MO 40)). A NDH Ministerial decree of 18th July 1941 ruled that the title 'Serbian Orthodox Church', was at discord with the new state. It was to be replaced by the 'Greek-Eastern Faith' as it had been prior to 1918 ((MO 20)). This appears to have been the first time the government officially drew a distinction between the Orthodox religion and the Serbian Orthodox Church. In a decree of the 4th December the 'Greek-Eastern Faith' and the Catholic Eastern Rite, were ordered to change from using the Julian to the Gregorian calender ((MO 20)). On 23rd February 1942 Marko Puk, Minister for Justice and Religion, spoke to the Sabor. He said that Ante Starcevic, founder of 'The Party of Right', had enshrined in clause 136 of its constitution, that religion must be free and not imposed by force. The Minister then announced:

Five days later Pavelic, in an address to the Sabor, again drew a distinction between the Orthodox religion and the Serbian Church. He explained that the Orthodox used to be known as the: 'Greek-Eastern Church', because its bishops were anointed by the Greek Patriarch. He continued:

The circular mentioned was apparently that of 30th August ((MO 58)), the one referred to by Stepinac in November 1941 (See Chapter III, D, final words of Cardinal Stepinac`s letter). Pavelic continued:

Afterwards, some Orthodox contacted A.R.Glavas, Secretary of the Department of Religion in the ministry of Justice and Religion ((MO 40)). He was a Franciscan who had deserted his parish. On March 23rd 1942 a legal notice was issued to establish the Croatian Orthodox Church ((MO 42)) becaming law on April 3rd ((RL 617)). Milos Obrknezevic, an Orthodox layman born in Belgrade but now living in Croatia, conducted negotiations ((MO 41)). Having spent his life employed in the legal department of the Serbian Orthodox Church, he was in an ideal position to undertake talks with Glavas. A constitution, based on the Serbian Church's one of 1931, was prepared. Obrknezevic had three meetings with Pavelic, who was mainly interested in linguistic and symbolic things to do with the Croatian language, and in the candidate for the highest position. Pavalic did not intervene in religious and canonical matters ((MO 41)). The Church's teachings were exactly the same as those in other Orthodox churches, but the church had to use the Croatian alphabet, language and the red, white and blue Croatian colours in her flag ((RL 255)). The legal title was: 'The Croatian Eastern Orthodox Church' ((RL 617)), but the word 'Eastern' tended to be dropped in normal conversation. The government would have the final decision regarding the appointment of bishops ((RL 255)). The former Metropolitan Germogen of Kief ((TB 28)), an elderly Russian monk who had been living in Yugoslavia since 1922, agreed to lead the new church. The Patriarch of Constantinople gave his approval for it to be led by a Patriarch ((MO 43)). According to Obrknezevic, the interned Serbian Patriarch Gavrilo Donzic and his deputy, Metropolitan Josif Cvljovic, were both unofficially informed of the negotiations and the proposal to elect Germogen as Patriarch. According to this source, Donzil agreed with the plans for the new Church, except that Germogen should be a metropolitan not a patriarch, with the status of his successor to be decided at a later date. So a metropolitan was appointed ((MO 43)), with legal provision made for a future patriarch ((RL 618)). The constitution of the church came into force on the 5th of June 1942. Two days later Germogen was enthroned in the Orthodox church of The Holy Transfiguration in Zagreb. The President of the Croatian Sabor, Marko Dosen, together with several ministers was present to pay respects ((MO 44)). Joso Dumandzic, a government minister, read the decree appointing Germogen. He said that the Croatian Orthodox Church was based on the national proverb: 'The brother is dear whatever his faith' ((MO 45)). Priests were released from internment to return to their flocks, and churches were reopened. Young student priests and clerics, still studying in the seminaries, were sent to administer parishes lacking pastors ((MO 46)). Others were sent to Bulgaria to complete their training. Eparchies were established at Brod, Sarajevo and Bosanski Petrovav ((MO 46)). The Romanian and Bulgarian Orthodox Churches approved of the new church ((TB 28)), but the Serbian Church in Belgrade condemned it ((SAA 25)). Metropolitan Germogen had a meeting with Archbishop Stepinac and Moslem leaders so as to establish friendly relations ((MO 46)). New prayer books were published with the only change being the use of the Latin alphabet in place of the Cyrillic ((MO 47)). The new church was given state financial assistance ((RL 618-9)), as were the Catholic, Moslem and Protestant religions ((TB 28)). The number of priests involved is disputed, but it appears there were seventy clergy by the end of 1942 ((MTA 158)). Obrknezevic names thirty senior priests decorated at Christmas 1942 and added that there were many younger clergy ((MO 47-8)). This church was strongest in peaceful and flat countryside of north-eastern Bosnia, ((MTA 158)) and carried out its spiritual work until the NDH was overrun by the Communist Partisans in 1945. Many Serbs saw its priests as traitors ((MTA 158)). Tiso executed eighty-five year old Metropolitan Germogen, another bishop ((SAA 179)) and many senior priests ((MO 49, SAB 122, SAA 26)). Obrknezevic was arrested but, as several prominent Communists owed their lives to the formation of this church, he was permitted to emigrate ((MO 49)). The Macedonians had also wished for independence or to be part of Bulgaria. Many teachers and priests had been deported or intimidated because they resisted serbianisation ((SG 302)). In April 1941 Macedonia was placed under Bulgarian administration. Metropolitan Josif of Skopje, a fellow Serbian bishop, 200-300 Serbian clergy, Macedonian priests married to Serbian wives and Serbian colonists were expelled ((SAA 11-13)). They were considered to be, 'the foremost carriers of Serbdom and Serbian Orthodoxy in Macedonia' ((JT 177, SAA 11)). The Macedonians and Bulgarians were Orthodox by religion but not Serbian Orthodox. After the war the Serbs reimposed their authority, but in 1967 the Macedonian Orthodox Church broke away from Serbian control ((SAA 286)). In 1993 Macedonia achieved political independence ((CBA 221)). The events in Macedonia with its Orthodox population, is a further indication that the motivation for the expulsion of Serbian clergy and their supporters by the non-Serb minorities was not religious but cultural, political and national. It is debatable whether the recognition of the Croatian Orthodox Church was an implementation of Ustasha principles or a reluctant move made under the pressure of events. Starcevic (1823-1896), founder of the Party of Right, had an Orthodox mother ((MO 37)) and the Ustasha considered themselves to be the continuation of his Party. While the whole tradition was of anti-Serbdom, which included the Serbian Church, this antagonism was not shown towards Orthodoxy as such. Eugen Kvaternik (1825-1871), granduncle of Slavko who had proclaimed Croatian Independence, had urged during the early days of the party that there should be an Orthodox Patriarch in Croatia ((MO 37)). The Ustasha had good relation with the Romanian and Bulgarian Orthodox Churches. It was Macedonian Orthodox nationalists, based in Bulgaria, who had trained the Ustasha prior to the war ((SCA 1)). An Orthodox Macedonian militant had assassinated King Alexander on behalf of the Ustasha in 1934. It was the Serbian Orthodox Church, not Orthodoxy as such, which the Ustasha opposed. From the beginning of the NDH, Orthodox personalities were welcomed in Ustasha circles provided they favoured Croatian Independence. Orthodox Ustasha officers included Lt. Markovic ((MO 59)). Generals Fedor Dragojlov and Duro Grujic, chiefs of staff in the Croatian army fighting the Chetniks and the Partisans, were Orthodox. General Lavoslav Milic, chief of military supplies, Colonel Jova Stajic and Major Vladimir Graovac were Orthodox. Graovac commanded a volunteer force ((SH 156)) of Croatian air force bombers in Russia ((MO 36-37)). Savo Besarovic and Uros Doder had seats in the 1942 Croatian Sabor, with Besarovic becoming a Minister in October 1943 ((MO 37, 10 18)). Many Orthodox financiers, scientists and lawyers had been loyal Croats and members of the Party of Right ((MO 36-38)). Josip Runjanin Composed the Croatian national anthem ((MO 36)). When in July 1941 the government replaced the, 'Serbian Orthodox' title by the 'Greek-Eastern Faith' ((SKP 112)), It was implicitly acknowledging an Orthodox religion free of Serbian control. The recognition of a Croatian Orthodox Church was a natural development of this and consistent with Ustasha principles, traditions and practice. On the other hand, the inflammatory remarks of Ustasha leaders like Milo Budek, the hard-line taken by General Slavko Kvaternik and the introduction of regulations regarding 'conversions', point to Ustasha policy during the sping and summer of 1941, as having been dominated by its violent wing. It was not until the autumn of 1941 and early 1942 that the more responsible and wiser elements in the Ustasha gained control. Copyright ©; ChurchinHistory 2004 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||