|

The ChurchinHistory Information Centre www.churchinhistory.org

JAMES II AND THE 'GLORIOUS REVOLUTION' OF

1688

CHAPTER X Whig literature was not merely clever in its misuse of words to discredit James. It also misused words to paint a bright picture of the alleged benefits of overthrowing a Catholic Monarch in 1688. They used such terms and phrases as The GLORIOUS Revolution - a FREE Parliament - a WILLIAMITE

army - A REVOLUTION - the INVITATION to William - William's RIGHT to intervene - SAVED the Anglican Church - The

TOLERATION ACT of 1689 - THE BILL OF RIGHTS - A FREE press - A STEP TOWARDS DEMOCRACY - Led to BETTER JUDICIAL

PRACTICE. a). 'GLORIOUS' (i.e. possessing honourable fame). At times a country finds itself suffering under a tyranny involving harsh suppression of all

opposition. There is vicious discrimination against dissidents, mass imprisonment without trial, torture, the killing

of agitators, and the hopelessness of achieving justice by peacefully . A revolution with the support of the populace

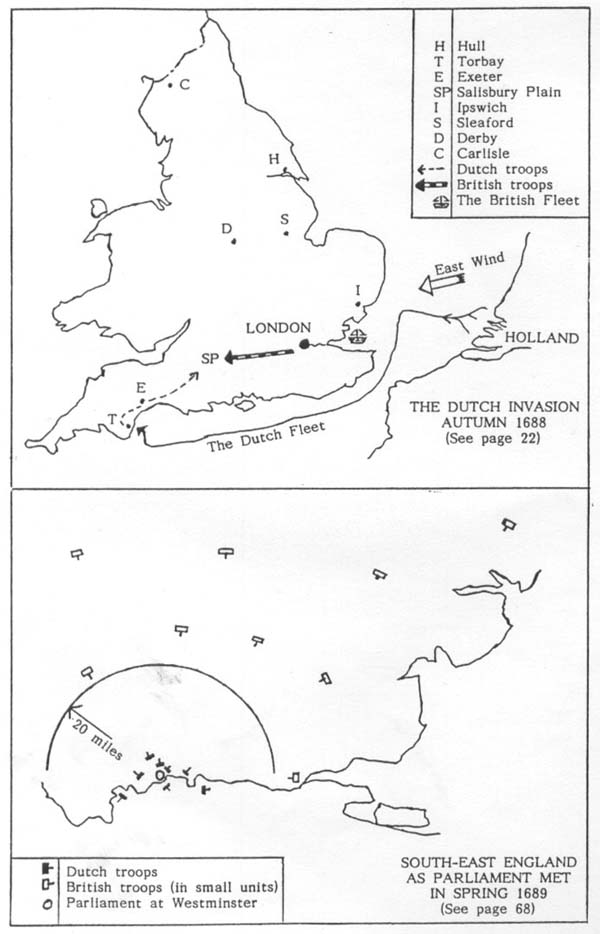

may in such circumstances be described as GLORIOUS. 1. Forcing an Oxford College to admit non-Anglican Dons and students. 4. Of using his royal powers excessively in order to fight discrimination in government institutions and the military forces, and to obtain a friendly Parliament. There was nothing GLORIOUS in overthrowing such a ruler. The action of a small group of army officers in disabling a section of the British army, as a foreign army invaded, would be more correctly described as 'traitorous'. In 1988 the Queen attended a joint meeting of the Houses of Parliament to commemorate: 'The Glorious Revolution'. The royal script-writers appear to have faced a dilemma in the face of modern historical research. The Queen said the events were: 'Glorious' because hardly anyone was killed. This definition avoided the traditional meaning of the word as used in official history for three hundred years. b). A FREE Parliament A major assertion of official history is that William enabled the English people, led by their lords, clergy and army, to hold a 'free parliament' in the spring of 1689. History books have maintained this illusion by omitting the circumstances in which the parliament, that deposed James and voted for the crowning of William, was held. ' ... a thick wall of silence has descended over the Dutch occupation of London in 1688-90. The whole business came to be seen as so improbable to later generations that by common consent, scholarly and popular, it was simply erased from record.' ((JII 128)). In December 1688 the Dutch assumed control of the national finances and administration. Dutch officers also directed the War office and ordered the English army to be sent away from London and dispersed into small units. ((JII 126)). The units were forbidden to come within 20 miles of the capital. Dutch troops were deployed to the north and west of London at Woolwich, Kensington, Chelsea,

Paddington and Richmond ((JII 128 and 146)). Others took control of St. James' Palace, Whitehall and Somerset

House ((JII 128)). British regiments in the Dutch army were quartered in the Tower and at Lambeth ((JII 145)),

making it difficult for them to communicate with the English army units to the north. Their commander was Hugh

Mackay who had lived in Holland since 1674, had a Dutch wife and was very loyal to Holland ((JII 145)). It is therefore false to claim that a free parliament met in 1689 in a free atmosphere to express the free wishes of the nation. c). A WILLIAMITE ARMY From Whig histories one would gain the impression that the national army supported William. But there was widespread dissatisfaction throughout the country. William feared a national uprising led by English army units. Of 40,000 in the British army, 10,000 were dismissed and 10,000 sent to man towns in Ireland. A further 10,000 were ordered to Holland. This left 10,000 English troops to face an occupation force of 19,000 ((JII 135)). There was army unrest and a regiment at Ipswich refused to embark, under a Dutch general, for Holland. Seizing cannon they marched to join pro-James forces in Scotland. It was politically embarrassing for the Dutch to attack British troops on English soil, but William couldn't rely on the loyalty of any English troops he might send against them. So 4,000 Dutch cavalry under General Ginkal were sent. They surrounded them at Sleaford in Lincolnshire. Being outnumbered, the British had to surrender and were quickly sent to Holland ((JII 144-5)). William warned his commander in Holland that the 10,000 British troops were unreliable. They were constantly toasting 'King James'. ((JII 145-6)). The Ipswich event led to the 1689 Mutiny Act ordering the death penalty for mutiny or desertion ((ECB32)). All fighting against James' supporters from 1689 till 1691 was, apart from Mackay, under the command of foreign generals. These were Soims, Ginkal, Schomberg, Wilhelm and Ruvigny ((JII 145)). The occupation of Ulster in 1689 was organised principally by Bentinck, Schomberg and Solms. Not one English minister or commander played a significant part in this major operation. Of Schomberg's eight aides, one only could speak English. ((JII 149)). It was Dutch, Danish and Huguenot troops supported by modern powerful Dutch artillery that won the battle of the Boyne ((JII 151)). The Dutch could not risking ordering English or Scottish troops to fire on James' army, so kept them in the rear ((JII 155)). In modern language, Britain had become a military satellite of Holland. d). A 'REVOLUTION' This word is defined as: 'the forcible substitution by subjects of a new government for old.'

((POD)).When a nation's army successfully invades the territory of another nation and the victorious leader forces

his new subjects to make him their king, the correct description of such an event is: 'occupation' or 'conquest'. Without money or influence, confined to their quarters in a hostile land and threatened with execution if they deserted, ordinary soldiers were not able to leave ((JCA 134)). When 200 were captured at sea they rejoiced ((JCA 122)), and Scottish soldiers, while guarding English troops who had been led into William's hands by their traitorous officers, drank James' health. Few British subjects were involved in the 1688 events, and those that were took a very subordinate part. 'The decisive decisions in 1688 were those made by William and Louis, rather than those of James, the seven bishops or even the seven signatories of the invitation to William' ((JRJ53)). On 22 January 1689 the House of Commons met and declared the throne to be vacant. They offered to elect William as king on certain conditions. This proposal abandoned the principle of hereditary kingship, and if accepted would have made the Monarch subordinate to Parliament, thereby establishing in effect a republican form of government. The House of Lords saw this as a threat to their own hereditary rights, and continued to consider James as King. Some wanted James to return but under limitations; others proposed that a Regent be appointed until James died, at which time Mary would succeed. Alternatively they considered making Mary queen immediately, with William as her consort. Constitutionally, James' son was next in line to the throne, but his right was ignored. On 5th February, William called the leaders of Parliament together, and informed them firmly that he would be neither Regent nor Prince Consort. If he was not appointed king for life he would return to Holland ((MAB 183)). Many had not resisted the invasion because William had said he was not coming to claim the crown but to press James to change his policies towards Parliament's laws. They were now appalled at what they had allowed to occur. Some had turned against James when his army was retreating, but if the Dutch army withdrew they would be swept from power and called to account by a returning James. They were aware that the British army, although dispersed, was full of bitter men. William won the vote by 64-46. But when account is taken of six pro-James Members who had been excluded from voting, and those who feared William's threat to leave the country, it can be seen that it was not the enthusiastic and overwhelming vote as it was later portrayed. So on 13 February the Crown was 'offered' jointly to William and Mary but: 'the sole and full

exercise of the regal power', was to be held by William ((MAB 183-5)). In the Declaration proclaimed by him

on landing in November, he had stated that: 'He abjured all thought of conquest' ((TM Vol. III, Ch ix)). In an attempt to give the invasion some form of moral authority, the Whigs with some Tory supporters ((ECC 1)) claimed that William had come at the invitation of leading gentlemen. These it was claimed were acting on behalf of the whole nation. Their action may be likened to the small Communist cliques in Eastern Europe between 1950 and 1990, 'inviting' Russian troops to invade so as to 'save' their country from libertarian moves being made to make their countries democratic. The 'letter of invitation' was dated 3rd June 1688, yet William first set sail in September, to be driven back by the weather. Historians today do not believe the Dutch could have gathered such a huge army and fleet together in three months. William had in fact taken the decision to invade in the previous April ((JRJ 250, MAB 91 and MA233)). The letter was in response to a communication from William indicating his invasion plans. The 'invitation' letter was one of association rather than one of invitation ((JRJ 240)). William was concerned that fear might cause his allies to hold back from their treachery at the critical moment. So William's agent made them send William a signed letter stating their intended treachery, thereby making it impossible for them not to carry out their role ((JRJ 240, MAB 121-3)). The writers claimed that 95% of the nation would support William, but admitted that they had very little definite support as: 'it be not safe to speak to many of them beforehand'. ((DCDA 120)). f). WILLIAM’S RIGHT TO INTERVENE. When one country decides to invade another it is necessary to find an excuse. In early 1688 William's wife Mary, being James' eldest child, was still next in succession to the English Crown. So William could claim he was merely bringing forward her succession in order to preserve law and English liberties. The situation did not justify this pretext but other aggressive wars have been launched with similar justifications. On 10 June 1688 James Francis Edward was born and as a son of James took precedence over Mary. William sent congratulations to his new nephew ((JH 266)), but William's right to invade was now even less. It was the English conspirators who thought of a way to overcome this problem and utilize the birth to their own advantage. With their letter of 'invitation' the conspirators told William he had injured his cause by congratulating James, because he could use the birth of the Prince as an excuse: 'your entering the kingdom in a hostile manner' ((DCDA 121)). A whispering campaign claimed that the queen had had a miscarriage and that another child had been brought into the bed in a bedpan. It was whispered that only 'Papists' were present at the birth and that it was a trick to deny: 'Protestant Mary' her rights. Rumours were also spread that James had VD and was therefore unable to have a healthy son. There was no evidence of this. Arabella, his former mistress, had born him four healthy children between 1670 and 1674 ((JH 168)). There had been rumours of a miscarriage at six months, but everyone at Court knew that they were unfounded. The actual birth was witnessed by the Queen Dowager, several Lords and Ladies both Catholic and non-Catholic, and members of the Privy Council. Many of the Ladies stood around the bed ((JH 267)). Few Royal births have been more fully documented ((MAB 118)), and at a special meeting of the Privy Council testimonies were given by the midwife and laundress ((MAB 148)). By the time George I was crowned in 1714 even the Whigs had been forced to abandon their falsehood ((BW 15)). But at the time, the conspiratorial lies were so effective that for several years few would dare challenge the accusation ((FCT 406)). When the Dutch army landed, William issued a declaration excusing his action. The Declaration was written in Dutch, with an abridged translation in English. After summarising the main Whig points of propaganda against James, it contained the words: 'lastly there were circumstances which raised a grave suspicion that the child who was called Prince of Wales was not really born of the Queen' ((TM Vol. III, Ch. ix)). The Earl of Shrewsbury, a prime mover in the conspiracy and whose signature headed the letter

of: 'invitation', later admitted that William would have invaded even if the Prince had never been born ((MAB 91)).

So the 'right' of William to invade, based on the hereditary right of his wife, was a gross deceit. g). William 'SAVED' the Anglican Church A major justification for supporting William's invasion was that it would save the freedom of the Anglican Church. It is therefore pertinent to examine whether the Church of England was free under Whig rule. 'The Tudors had failed to bring all within their form of Church discipline, but had made the Church an instrument of state policy' ((BW 68)), 'but at no time in our history was the Anglican Church in England and Ireland so completely subservient to the purposes of the civil government as under the Whigs'. ((BW 68)). 'The Established Religion was regarded by most politicians and by many churchmen first as a safeguard for the Whig system of government, especially as a valuable form of police control over the lower classes'. ((BW 76)). 'The bishops were mainly chosen for their sympathy with Whig doctrines and their capacity for enforcing them'. ((BW 76)). The usual qualifications of a bishop for office was political service or the support of powerful patrons in the Whig party ((BW 78)). Of vital concern to the freedom of the Anglican Church was the ability for its bishops and clergy to meet and formulate policy regarding doctrines, discipline and social comment. Apart from the period between 1700 and 1717, when Queen Anne and the Tories had influence, and one occasion in 1741, Convocation was not permitted to meet during the long period of Whig rule ((BW 82)). This situation, combined with the social divide between bishops, clergy and laity, led to lethargy. There was uninspired preaching, practice, spirituality and the failure to integrate the Methodist Movement within the Church's structures ((BW 82-83)). 'Religion has rarely been so uninspired as in this century' ((BW 83)). Religion was discussed by many writers of the time, but they showed little apprehension of the spiritual, and tended towards Deism and neglect of Christian practice and doctrine ((BW 83)). Apart from a few great men and a sprinkling of some devoted country parsons: 'the Established Church throughout the century was more of a political system tinged with the minimum of Christian doctrine than a living example of faith animating the community' ((BW 94)). This compares with Church life under James, when the Established Church 'Was beginning to flourish more than it had ever done since the Reformation' ((JRP 8)). The Whigs depicted themselves as full of indignation that a non-Anglican king, such as James,

should govern the Anglican Church. Yet within a few months, they had enthroned a king who was neither Anglican

nor English as its governing head ((MAB 84)). William of Orange was a Dutch Calvinist ((HTJY 34)) who ordered

the Anglican clergy what to preach ((MAB 190)). This Act has been presented as an historic revolutionary achievement in its granting of religious liberty. But in reality it was a retrograde step. Under James, religious minorities had been granted freedom of worship and the end of most civic discrimination against their members. But: 'in order to placate the English upper classes, William and Mary omitted to fulfil even the terms of their 1687 declaration. Unlike James' Declaration, the Williamite 1689 Act was prefaced by no doctrine of tolerance. The motives for it were plainly political. Not a single old law against religious liberty was repealed or suspended; instead dissenters were granted relief by being "exempted from the penalties of certaine Lawes". All the penal laws were held to be in force, particularly against Catholics and Unitarians, who received no relief whatsoever despite the promises of 1687' ((HK 211)). 'With the Toleration Act freedom went into retreat' ((HT 211)). 'The so-called Toleration Act was as grudging as possible; it merely exempted Dissenters (except those who rejected the doctrine of the Trinity) from the Penal Laws. William's suggestion that dissenters should be made capable of holding office provoked an explosion' ((JRJ319)). The Act permitted non-Anglican Protestants and Jews to conduct worship, but they were still barred from voting, taking part in Parliament, local government, state administration, leadership in the armed forces, attending a University, opening a school or being a teacher. The laws were not consistently enforced but could be used to cause suffering to Dissenters.

In 1742 the City of London was raising money to build the new Mansion House. The Corporation passed a by-law that anyone declining nomination for the office of sheriff would be fined. Then for several years in succession Protestant Dissenters, known to be unwilling to qualify by receiving Anglican Communion, were nominated and elected. By 1754 the fines had reached £15,000 ((BW 71)). Additional anti-Catholic laws prevented a Catholic acting as a guardian, sending a child to a school abroad, carrying arms, owning much property, marrying a Protestant who owned property, being a solicitor or possessing a horse worth more than £5 ((BW 183)). Catholic landowners paid double taxes. ((MDRL 115)). To boast of a toleration act which left minorities with less freedom than they possessed previously is another example of a hypocritical misuse of words. Although James' acts had not been indorsed by Parliament, there was real religious freedom prior to his overthrow. 'It may also be said that if James had not made his stand in the fight for religious toleration, the recognition of the legitimacy of non-Conformists in 1689 would have been unlikely'((MAB190)). i). THE BILL OF RIGHTS This Bill was passed on 25th October 1689, not as a reaction to the rule of James but as an attempt to limit the power now in William's hands. It tried to remove the King's right to use the dispensing power widely, levy taxes, create Church Commissions and keep a standing army. These rights were transferred to the small group of landowners and rich merchants who now controlled Parliament. These 'rights' did not benefit 95% of the population. When the rich and powerful were abusing their new powers, the poor could not appeal for assistance to a strong king or independent Anglican Church. There were about 200 lay Peers in the House of Lords ((BW 22)), who represented 200 powerful families. There were also 26 bishops appointed by the government to control the State Church. These few families had unassailable power because of their ownership of vast estates, covering two-thirds of the country ((WE 555)). This gave them control of the House of Commons as well as of the House of Lords. Voting was not secret so fear, bribery and the desire to gain approval of landowner and employer made elections for the 80 County Members of Parliament undemocratic. Small cliques of local magnates and country gentlemen chose the candidates. Contested elections were rare ((BW 26)). The total electorate of the 203 cities and boroughs in England was 85,000, with 181 constituencies having less than 1,000 voters each, making bribery and threats very effective. The small boroughs had a bewildering variety of electoral systems, lending themselves to gerrymandering. The great majority of Members of Parliament represented their personal interests and those of their patrons. Some boroughs were frankly the property of patrons who could give or sell the seat ((BW 27)). As late as 1790 there were a mere 2,655 voters in the Scottish counties and only half were genuine freeholders, the others being created by the landowners. The 45 Scottish Members were elected on such a narrow basis that the government, by means of patronage and bribery, could assure itself of at least a majority from these constituencies ((BW 28)). The revolutionary families 'packed' Parliament far more thoroughly and permanently than James had attempted. The chief organ of local government was the ‘Justice of the Peace’ ((BW 49)). His power in urban

as well as in rural districts was immense, being an administrator with juridical functions ((BW 50)). These J.P.s

were local despots ((BW 52)) and generally belonged to the ruling political party ((BW 54)). 'Civil Society, the chief end wherof is the preservation of property...' 'The great end of Men's entering into Society being the enjoyment of their properties in peace and safety' ((BW 5)). Locke and most other economists viewed poverty as almost a crime and therefore deserved ((BW 137)). The efforts of individual philanthropists were swamped by the spirit of the age ((BW139)). The most marked characteristic of Whig rule was the great cleavage between the well-to-do: 'persons of fashion and fortune', and the poor: 'lower order of people' ((BW 128)). Class barriers were far less when Charles and James were kings ((BW 128)). As a rule the poor were regarded as a class apart, to be ignored except when their hardships made them boisterous ((BW 129)). No efforts were made to enforce the laws made in previous generations. A visitor remarked in 1730 that, although there were: 'excellent laws for maintenance of the poor . . . few nations are more burdened with them, there not being many countries where the poor are in a worse condition'. ((BW 130)). Wages were kept to the minimum, and prices high, on the excuse that this made the poor work harder ((BW 143)). At times there was starvation amongst the poor ((BW 126)). Entertainments for working people were repressed so they would not waste their time and money ((BW 129)). Two thirds of pauper children in the Work Houses died before they were five, and those that survived were put to work at low pay with no control over the way their masters treated them, which was often most inhumane ((BW 132)). The ruling class lacked for nothing and, if a member did become short of money, he was assured of a government post involving little work, as a pension ((BW 146)). The words: 'freedom ... from excessive bail, fines and cruel punishments', in the 'Bill of Rights', applied to the Whig ruling class only. Punishments for the ordinary person included pillory and whipping, burning in the hand, transportation and hanging ((BW 135)). By 1760 death was the penalty for 160 felonies including sheep-stealing, cutting down a cherry tree, being seen for a month with gypsies, and petty larcenies ((BW 62)). The Vagrancy Acts ordered 'rogues, vagabonds and sturdy beggars' to be whipped 'until bloody', and then sent to houses of correction ((BW130)). Local authorities saw prisons as a method of making money. Prisoners awaiting trial had to pay to have their cell door opened, for beds, for putting on and taking off irons, and discharge from jail. Prisoners of both sexes were herded into overcrowded insanitary rooms with malignant forms of typhus almost endemic. In 1716 there were 60,000 people in prison for debt, some for the smallest sums. Of 800 prisoners in the Marshalsea jail 300 died in less than three months.((BW135)). Education for both rich and poor reached its lowest level compared with previous centuries and with those to come ((BW 139)). The 'Glorious Revolution' made the Charters of Universities, Parliament, Corporations and Charitable Endowments inviolate ((GMT 365)), so these vested interests were placed outside the control of public influence. The town Corporations could spend their revenues on gluttonous feasts while neglecting their duties ((GMT 365)). Headmasters of Endowed Schools could give poor service and even close schools, while still drawing income from the endowment ((GMT 365)). At both Universities the chartered monopoly led to lazy, self-indulgent Dons who almost entirely neglected the undergraduates. The number in attendance fell to less than half those in the reign of Charles II ((GMT 365)). Professors seldom performed their functions ((GMT 366)). By 1770 serious examinations for degrees had ceased at Oxford, although the teaching of Mathematics at Cambridge was to a good standard ((GMT 366)). As the endowed grammar schools decayed, secondary education decreased despite a growing population ((GMT 364)). Protestant Dissenters managed to establish some private Academies of a high standard, but studies had to be finished abroad. If Catholic children went abroad for education they were breaking the law ((BW 88)). Attempts by Anglicans to improve education made little progress once the Whigs gained full power in 1730 ((BW 141)). With Whig Party workers being appointed to professorships, the teaching of Law at the Inns of Court and Oxford was practically non-existent. Men truly dedicated to the Law gave private lectures ((BW 62)). After 1744 it was not necessary to be learned in the law in order to become a J.P. ((BW 50)). In 1721 the beginnings of Trade Unions were made illegal and strikes suppressed by the military,

yet combinations of employers were permitted. ((BW 143)). It is not surprising that in this brutal age, bull baiting,

cock fighting and throwing, badger baiting, goose riding and public hangings were seen as amusements. They encouraged

the barbarous custom peculiar to the English of insulting and jesting at misery ((BW 135)). Holidays were at Easter,

Christmas, Whitsuntide and eight, 'Hanging Days' at Tyburn ((BW 132)). 'England had the bloodiest penal code in

enlightened Europe' ((WAS 248)). After the passing of the 'Bill of Rights' the situation in Britain changed. "For William's war, the system of pressing, in abeyance at first, was soon stretched to the utmost and was organised with almost brutal efficiency." Even while the ships were laid up during the winter, it was thought too risky to allow the men to go home; so they were kept on board . . .' ((DO 330)). 'Another of the terrors of London was the fear of being suddenly seized by the licensed press-gangs of the navy . . .' ((BW 133)). This was in about 1716. During the reign of George II, Admiral Vernon declared that: "Our fleets are defrauded by injustice, manned by violence and maintained by cruelty" ((GMT 348)). j). A FREE PRESS In 1695 the Licensing Act was not renewed and this: 'has usually been hailed as a triumph for freedom of the Press, and even as evidence of greater enlightenment after the Revolution. But contemporaries did not think so' ((OD 511)). 'Cromwell effectively created a state monopoly of news . . . the system was transferred to the Royalists, and in 1662 the Press was formally placed under tight Parliamentary control . . .' ((GB 83)). When Charles suspended Parliament in 1679 the Act could not be renewed. It was then that the Titus Oates and other lying Whig propaganda poured from the presses with such dramatic results. '... in the 17th Century both government and its subjects were inexperienced in either digesting the printed page or judging its effects' ((FSS 249)). It did not operate again until Parliament met in 1685. In 1688 the Crown, without a formal statement, relinquished control of the Press to Parliament ((FSS 300)). The Revolutionary Parliament renewed the Licencing Act and it operated until 1695. In 1694 the House of Commons explained to the House of Lords why they did not wish to renew the Act. 'All 18 reasons were of expediency, not moral or philosophical' ((FSS 306)). They were mainly concerned with restraints on commerce, such as causing high monopoly book prices, a closed-shop for book-sellers; delaying the importation of foreign books through the customs and being unworkable due to the increasing quantities involved. There is no reason to presume that this development would not have taken place if James had continued in power. The granting of religious liberty under him would automatically have resulted in a more open expression of religious and philosophical opinions. Most likely James would have continued to use the laws of seditious libel with regard to political opinion, but this is what the Whigs also did after the 'Revolution'. 'Parliamentary leaders objected to publicity. Curiously the Revolution of 1688 made no observable change in this attitude . . .' ((FSS 265)). 'There was a strict control over political opinion' ((OD 512)). 'In 1704 Chief Justice Holt stated that it was necessary for all governments, that people should have a good opinion of it, and that it wasn't maladministered by corrupt persons'. ((FSS 271)). Any criticism of the government constituted seditious libel ((OD 511)). 'The powers of Parliament were as vague and elastic as those that had been held by Charles and James ((FSS 276)). In May 1712 registration and taxation was imposed on all aspects of newspaper and pamphlet production, thereby putting the media into the hands of the rich and established sections of society. It was not until 1771, the year following the end of Whig rule, that debates in Parliament were allowed to be reported. ((FSS 311)). k). A STEP TOWARDS DEMOCRACY The assertion is made that by overthrowing an absolute Monarch in 1688, Britain was enabled to

evolve gradually towards democracy without violent upheavals. The partnership was threatened when Parliament, by means of the Exclusion Act, attempted to abolish the hereditary right of succession. Charles' legal suspension of Parliament was necessary to defend the Monarchy and partnership. James preferred to work in a team, and take advice from his assistants ((JH 158)). There is no evidence that James wanted absolute power for its own sake. His one reason for trying to exercise his rights to their maximum was the issue of religious freedom. If Parliament had agreed to implement the 1660 Declaration of Breda, there would have been no cause for the partnership between King and Parliament to have broken down. This relationship could have evolved over the generations towards a system of government akin to what we possess now. The very fact of religious freedom would have meant a freer circulation of literature and a more open intellectual climate, which would have prepared the way for democracy. The idea that 1688 opened the way for eventual democracy is based on the Whig myth that James was a tyrant grasping for absolute power. 1). LED TO BETTER JUDICIAL PRACTICE In 1714 a law to make the judiciary independent of government became operative. This is claimed as a delayed fruit of 1688. But the development of improved Court practice was to be seen prior to this date. In 1670 the jury had been freed from the threat of being penalised for giving the 'wrong' decision, in 1677 the criteria for considering evidence had been improved, and in 1679 the Habeas Corpus Act had been passed. There is no reason to presume this trend would have stopped because James had forced Parliament to grant religious freedom. CHAPTER XI A). THE NEED FOR ANTI-CATHOLICISM For ten years following the restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, political life flowed in two streams: 1. The Royalist, which upheld the hereditary rights of Monarchy working in cooperation with Parliament. 2. The Republican, which aimed to transfer effective power to Parliament. Republicanism was a small and dying force until James, the heir to the throne, became a Catholic in 1673. This enabled the Republicans to re-kindle anti-Papal fears amongst many Royalists. These Royalists were willing, through fear of having a Catholic King, to abandon their loyalist principles of hereditary monarchy. They would ally themselves with the Republicans who were becoming known as 'Whigs'. So from about 1673 till nearly 1770, political opinion came flow in three streams: l. Tories who, although mostly anti-Catholic ((ECA 3)), upheld the royalist hereditary principle regardless of a king's religion. After 1688 they remained loyal to James and became known as 'Jacobites'. ((EC 17-19)). 2. Tories whose royalist principles were overcome by fear of Catholicism. They retained the name of 'Tories' and eventually supported the Protestant Hanoverian kings, who reigned following the death of Queen Anne. 3. Whigs, most of who were republican at heart and wanted the aristocracy to exercise all power through Parliament, who saw the Monarch as a necessary symbol with which to maintain the loyalty of the lower classes. As William of Orange was primarily concerned with using the British army and navy, he let the Whigs run the internal affairs of the country. When he and his wife Mary died, the Tories ignored the claim of James' son who was a Catholic, and agreed to let the Whigs place Anne, James' youngest daughter, on the throne. The Tories felt there was some continuity of the royal family. In 1712 Anne died without children and there were no Protestant members of the Stuart royal family available to be crowned. The next in line was a distant Protestant Prince who ruled his Hanoverian domains as a paternal despot without a Parliament ((BW 13-14)). He had divorced his wife before shutting her up in a fortress for the rest of her life ((BW 11)), and had replaced her with three mistresses ((BW 152)). Most Tories were aghast at the prospect of such a King and swung to support the Jacobites. But, by postponing the elections for Parliament, the Whigs established this prince on the throne as George I. A Jacobite rising in 1715 failed. George I and his son George II didn't bother to learn English and lived in Germany ((BW 14)).

This led to the Whigs having much independence in the administration of the country, but also to increased support

for the Jacobites. 'The Jacobite leaders didn't realise, as Charles did, that a rebellion on the defensive was doomed' ((CPB 377)). As the Jacobites withdrew, the Dutch reoccupied Carlisle ((ECC 101)) and popular support swung to the apparently winning side. 'The almost unanimous opinion of modern writers is that the Prince was right, and Charles could have restored the native house without the aid of a foreign bayonet' ((CPB 373)). King George V said that if Charles had marched south, "I should not have been king" ((CPB373)). It was the very strength of the Jacobite threat, which lasted for nearly 70 years, that made it imperative for the Whigs to saturate the British mind with anti-Catholic propaganda. It was the only way the Whigs could persuade the Tories not to unite with the Jacobites. 'That the faults of James have had more attention from historians than his virtues cannot be denied, and the reason is not far to seek. His cause received so much support that more than half a century after he had lost his throne his grandson came within an ace of recovering it, and thus it was a matter of life and death for the Whig oligarchs to denigrate his memory. He was depicted as a veritable ogre, and the adherents of the Hanoverian regime never tired of denouncing the terrible state of affairs which were supposed to have existed while he was on the throne' ((CPA 249)). James II, in his Memoirs wrote of the republican faction trying to: 'convince the nation with fears' ((JH 249)). A modern author, describing the events of 1745 has written: "The stress which the Whigs laid upon religion shows very clearly what those astute politicians believed to be the most effective argument against Charles" ((CPB 366)). B). THE END OF WHIG POWER The failure of the 1745 rebellion led to a collapse of hope amongst the Jacobites. When George III was crowned in 1760 most accepted him as king. He had been born in England, spoke the language, was very patriotic and a pious Anglican, not like his dissolute father and grandfather. So his character made their acceptance easier. This meant that the Tories were again united and by 1770, with the aid of the king, they had taken power from the Whigs. The Whigs had portrayed Catholics as 'agents of Rome' dedicated to the overthrow of 'British Liberties'. In pursuing this policy they had caused the Catholic communities in Ireland, Quebec (Canada) and the highlands of Scotland, to be alienated from the Crown. Although the Tories had been educated during the 70 years of Whig rule, and had thereby absorbed much prejudice against Catholics, they were more open minded and realised that Catholic alienation was not due to their religious beliefs, but to the manner in which they were being treated. In 1774 the Catholics of Quebec were granted liberty of worship, and in the same year an Irish Relief Bill was passed. An Act of 1778 freed priests in England from liability of imprisonment for offering Mass, and permitted Catholics to inherit property. The 1791 Constitutional Act granted extensive rights to the Catholics of Quebec, and in 1793 Irish Catholics were permitted to vote, sit on juries and occupy some administrative positions. The Whigs were out of power for 60 years and changed from defending vested interests to representing the advocates of social justice. Between 1800 and 1830 they assisted the reformist wing of the Tories to end the transportation of slaves ((OAS 179)), humanize the prison system ((HAC 146)), grant most civic rights to Protestant Dissenters, and in 1829 to Catholics ((HAC 148)). As the Tories were now supporting a Protestant King, anti-Catholic prejudice could not be used against them, so it was dropped from Whig literature. Much of the way of life established by the 'Glorious Revolution' had now been swept away, and by the time they were returned to power in 1830 the Whigs had become more libertarian than the Tories, eventually changing their name to 'The Liberal Party'. But the earlier Whigs had left a legacy of anti-Catholic myths deeply imbedded in history books, monuments and folklore. CHAPTER XII The manner in which historical studies were treated during the period of Whig rule is a significant factor when considering the way James II has been portrayed in history books. 'By the eighteenth century History, the best preparation for public life, appears to have been entirely neglected in the great schools of Eton, Winchester and Westminster' ((BW 139)). 'At neither Oxford nor Cambridge did the professors of history, instituted by George I in 1724 for the express purpose of training public servants, appear to have given any lectures during this period ((BW 140)). 'No lecture was delivered by any Regius Professor of Modern History at Cambridge between 1725 and 1773'. ((GMT 366)). In this void the pseudo-history of anti-Catholic myths and slogans established itself. During the first half of the 19th Century a slow revival of historical studies enabled academic circles to begin freeing themselves from 'Whiggish History'. But then Thomas Macaulay made his immense contribution to 'popular history'. He was a journalist and Whig M.P. but, between 1828 and his death in 1860, he concentrated on historical writing. He was not a trained historian, but made history the favourite reading of the general public of his day ((ABB 65 & 102)). He used his journalistic talents to portray historical events as battles between good and evil, Whigs and Tories. But: 'he saw men and their motives too much in black and white, and the habits of Party oratory tended to intensify still more these lights and shades' ((ABB 68)). William of Orange was his hero ((ABB 102)), so James was made wholly bad and William wholly good ((ABB 68)). 'The splendid rhetoric, that carries its readers onto so many heights, too often distorts the truth or conceals the awkward fact which would spoil it' ((ABB 68)). Macaulay’s History has now been shown to be full of numerous deliberate misrepresentations of well-documented facts ((JRJ 7, FCT 73, JH 146, MA 162, ABB 68)). Some of his errors are excusable. ‘Macaulay's ignorance of contemporary correspondence necessarily vitiates the value of much of his history’. ((ABB 64)). So his sense of proportion is distorted. A printed fable or libel, invented long after the time to which it refers, is allowed to appear in his pages because he was unaware of contemporary letters that proved its falsehood ((ABB 64)). 'He was too ready to take at their face value, tales emanating from republican printing presses during the last years of the Stuart regime, from which he would have drawn back in horror, had he been better acquainted with the past histories and characters of those who wrote them' ((ABB62)). Due to these grave errors in his writings, it is now agreed that: 'Through his genius the whole focus of English history becomes in due course distorted' ((ABB 12)). 'Sales of his "History of England" broke all records for this type of book and continued to sell widely well after his death' ((ABB 102)). Because of his simple, exciting and interesting style, his portrayal of historical events came to dominate school history teaching for several generations. 'For one scholar with sufficient judgement and knowledge of the facts to correct his superficial generalisations, there were a hundred journalists, schoolmasters and textbook writers ready to absorb them with uncritical delight and transmit them to posterity' ((ABB 12)). Macaulay was not personally anti-Catholic, and he advocated emancipation. But through his pen

the anti-Catholic myths of 1688 became part of English culture. Although blatant errors are now not so often repeated,

the attitude of prejudice towards James and his religion to which they gave birth, still remain. CHAPTER XIII In explaining historical situations involving anti-Catholicism, there is a danger that blame for injustices may become ascribed to innocent individuals, organisations or beliefs. So often we find that political forces exploited genuine and worthy causes. The leaders of Parliament during the reign of Charles II, claimed to be defending the Church of England and Protestantism. But did they have any right to appropriate these names to themselves? King Louis of France was claiming to be acting on behalf of Catholicism, and in the modern world racists have acted in the name of defending Christianity. Communists claimed to be fighting for: "peoples' democracy". Dictators have achieved power in the name of liberty. So when a political movement claims to be acting from religious motives, its credentials need to be checked carefully. 1. Since Elizabeth I, Parliament had repeatedly called for stricter anti-Catholic laws and offered rewards to those who betrayed a priest. This implies that few Anglicans or Dissenters would betray priests due to religious motives. 2.The action of organised London mobs, dedicated politicians and pamphleteers, should not be taken as indicating the feelings of ordinary Anglicans. Some of the mobs blasphemed the Cross ((ABA 29)). 3. By 1685 most Protestants were anti-Catholic, but this did not necessarily spring from religious belief. It came from generations of propaganda depicting Catholics as a threat to English freedom. It is easy to understand how a zealous reader of the Bible, who is taught that Catholics wish to burn all Bibles, will have his religious idealism channelled into hating the Catholic Church. By the end of the 17th century few knew Catholics personally, so had little idea of their real beliefs. Even when a Catholic denied accusations he was not believed. The population had been taught that Catholics could lie if it would help spread their faith. From the replies to the 1687-8 canvass by James, most Anglicans were prepared to live peaceably with Catholics and Dissenters including non-Christians ((HTJY 31)). But fear of the Pope made them want to exclude Catholics from public office. For them 'The Penal Laws and Test Acts were political not religious discrimination' ((HTJY 31)). 4. Clarendon was responsible for promoting persecuting laws during the reign of Charles II, but he was not a devout Anglican. He: 'regarded the fundamentals of religion as few and simple and considered the particular form adopted should be dictated by convenience and by the needs of the civil state' ((JM 94)). 'At the Restoration it was politically expedient to extend the boundaries of the Church and to calm partisan differences' ((JM 94)). 5. An example of how a deeply religious person could be induced to act unjustly is illustrated in the life of Richard Baxter, the Presbyterian leader. He was at a Puritan meeting when he and two others discovered that: 'the first lively motions that awakened their souls to a serious resolved care of their salvation', was the reading of a certain book. Later he learnt that a Jesuit priest had written it (the printer had omitted passages which would have indicated its Catholic authorship). Baxter later wrote that he had: 'met with several eminent Christians that magnified the good they had received from that book' ((FJP 264-66)). This experience affected his attitude towards 'Papists'. He wrote an article: 'The Duty of all other Christians towards the Papists in order to the promotion of the common interests of Christianity'. This treatise reads like a modern ecumenical document, with such phrases as: 'We must acknowledge and commend all that is good among them, and must truly understand in what we are agreed'. It recommends the reading of Papist books so that: 'we should profit by each other, and love his word whoever writeth it'. ((FJP266)). He wrote that Protestants must not judge all Catholics as bad just because some give scandal. He extended his positive approach to the Catholic Church as an institution, when he urged the recognition of: 'what good use God hath made of Rome's grandeur, unity and concord', in preserving Europe from the Heathen. ((FJP264-265)). He was attacked when he stated that the Beast of the Apocalypse referred to pagan Rome, not to the Pope, and that Babylon did not symbolise papal Rome ((FJP142)). Despite this outlook he welcomed the overthrow of James. He had been taught that: 'the Catholic creed bound the Catholic to owe no authority, whether of God or man, except Rome, so every sincere Catholic must needs be a potential rebel against the king'. He believed that Roman agents were at work, they would stick at nothing to bring about their end; that they had caused the Fire of London; were gathering Horse and Arms; had persuaded the Dutch to declare war on England in 1670; and had organised the plot of 1678 exposed by Titus Oates ((FJP 129-130)). He even called Fr. Parsons, author of the book he so strongly praised; 'a most traitorous Jesuit' ((FJP 265)). 'For months and even years the fear of Popery, It is clear, was uppermost in his mind' ((FJP130)). So a good man had been manipulated into supporting bigotry and opposing a zealous king with whom he had so much in common, and who had helped to obtain his release from prison. His zeal was also misdirected when he presented a petition for the expulsion of all Jews from the country ((AMH 211)). 6. The revolutionaries were not devout Protestants. One commentator at the time wrote, concerning those gathering around William in Holland: 'There is not in Hell a wickeder crew. Men who plotted with Shaftesbury during the Titus Oates period and had nearly sent Samuel Pepys to the gallows in 1679. There was Harbord and Aaron Smith who had bribed false witnesses against Pepys, and Widman and Scott who spoke of hanging the baby Prince in his swaddling clothes. At their head the dissolute, foul-tongued Herbert who was placed in command of the fleet' ((ABA 135)). Herbert had been dismissed by James in the spring of 1687 because Pepys discovered £4,000 had disappeared while he was serving in the Mediterranean. As he was unable to account for slaves he had starved or sold, further enquiries were pending ((ABA 39)). He was reported in 1663 to have kept a harem in Tangier ((MAB 121)). This Herbert was godless, yet Whig propaganda built him up as a man of high principles, who had resigned a well-paid position rather than become a Catholic and disown his 'Protestant' beliefs and heritage. The army conspirators were: 'hard and dissipated men like Kirke and Trelawney and fashionable young rakes from the disreputable Rose Tavern'. ((JCA 164)). 'Those who had made the revolution were mainly composed of men who had very dishonourable and shameful careers' ((ABA 221)). 7. It was the godless Herbert who took the 'invitation' to William, asking him to save 'Protestantism'. He compares sharply with the man James had earlier sent to William asking him for his moral support in favour of religious freedom ((FCT 352)). This was William Penn, a life long friend of James and his assistant in drafting the Declaration of Indulgence together with writing pamphlets to promote James' cause ((JRJ 115-8)). He became chief organiser in the campaign to achieve a libertarian Parliament ((JRJ 132-34)), and recruited supporters for James throughout the country ((JRJ 144)), and remained loyal after the invasion at the risk of his life ((FCT 309)). Historians rightly depict William Penn as a very good man, tirelessly working as a Quaker for

peace and freedom. When they also accept the caricature of James as being a: 'Papist Tyrant', they find it difficult

to reconcile how the two men worked together. They use such phrases as: 'extraordinary, indeed inexplicable friendship',

or: 'what in Penn attracted James is difficult to see'. ((FCT 309)). But once a true picture of James is grasped,

the problem disappears. 9. One reason some leading political Anglicans favoured James being excluded from the throne, was a genuine fear amongst the well-to-do that unless the Exclusion Bill was passed, a Republic would eventually be established ((MAB 30)). 10. The great majority of those who worked with James during 1688 were pious Anglicans or Protestant Dissenters. Whig 'histories' have naturally ignored them, and once William was in power, they kept out of the public eye. They have therefore not been given due credit for working for a free society. It is also noticeable that the period of Penn's life, when he was at the peak of his political career and influence, tends to be glossed over by some commentators.

12. The treachery of the small group of army officers took the country by surprise ((JPKB 159)), and it was not part of a broadly based religiously inspired movement to overthrow the king. It has been pointed out that: 'the most ferocious opponents of the Church of Rome were frequently, in the 17th Century as now, not very conscientious or reputable adherents of their own churches' ((FCT 97)). We may add, when considering the persecution of the French Huguenots and other incidents in history, that the most ferocious opponents of Protestantism were frequently not very conscientious adherents of Rome. MODERN HISTORICAL RESEARCH For generations the independent minded historian who challenged aspects of 'The Whig view of history' was ridiculed as a Jacobite romantic out of touch with the real world. But in the early part of this century Hilaire Belloc, educated in France prior to attending Oxford University as a mature student, used his journalistic skill to bring the issue into the open. In 1953 the historian Hugh Ross Williamson wrote: "Twenty years ago I found it difficult to read him without anger . . . My mind was not changed by reading Belloc but by studying sources, which revealed ... the general rightness of Belloc... "Since then Papers read at Special Conferences in 1979 and 1987 have been edited by Eveline Cruickshanks and published as: 'Ideology and Conspiracy' and: 'The Jacobite Challenge'. More recently, Meriol Trevor, W.A.Speck and Jonathan Israel have published books based on contemporary sources and original archival materials. These have further contributed to undermining 'official history'. These publications do not explicitly examine the success of Whig propaganda in moulding public opinion to be prejudiced against the Catholic Church. But they are destroying the framework within which this anti-Catholicism is set. APPENDIX: CLAUSE 2 OF THE SECRET TREATY OF DOVER The lord king of Great Britain, being convinced of the truth of the Catholic religion, and resolved to declare it and reconcile himself with the Church of Rome as soon as the welfare of his kingdom will permit, has every reason to hope and expect from the affection and loyalty of his subjects that none of them, even of those upon whom God may not yet have conferred his divine grace so abundantly as to incline them by that august example to turn to the true faith, will ever fail in the obedience that all peoples owe to their sovereigns, even of a different religion. Nevertheless, as there are sometimes mischievous and unquiet spirits who seek to disturb the public peace, especially when they can conceal their wicked designs under the plausible excuse of religion, his Majesty of Great Britain, who has nothing more at heart (after the quiet of his own conscience) than to confirm the peace which the mildness of his government has gained for his subjects, has concluded that the best means to prevent any alteration in it would be to make himself assured in case of need of the assistance of his most Christian Majesty, who, wishing in this case to give to the lord king of Great Britain an unquestionable proof of the reality of his friendship, and to contribute to the success of so glorious a design, and one of such service not merely to his Majesty of Great Britain but also to the whole Catholic religion, has promised and promises to give for that purpose to the said lord king of Great Britain the sum of two million livres tournois, of which half shall be paid three months after the exchange of the ratifications of the present treaty in specie to the order of the said lord king of Great Britain at Calais, Dieppe or Havre de Grace, or remitted by letters of exchange to London at the risk, peril and expense of the said most Christian king, and the other half in the same manner three months later. In addition the said most Christian king binds himself to assist his Majesty of Great Britain in case of need with troops to the number of 6,000 foot-soldiers, and even to raise and maintain them at his own expense, so far as the said lord king of Great Britain finds need of them for the execution of his design; and the said troops shall be transported by ships of the king of Great Britain to such places and ports as he shall consider most convenient for the good of his service, and from the day of their embarkation shall be paid, as agreed, by his most Christian Majesty, and shall obey the orders of the said lord king of Great Britain. And the time of the said declaration of Catholicism is left entirely to the choice of the said lord king of Great Britain. ENGLISH HISTORICAL DOCUMENTS 1660-1714 by DAVID C DOUGLAS Item 338 Page 863

REFERENCES [Page numbers in text] ABA.......Pepys and The Revolution by Arthur Bryant, 1979. ABB.......Macaulay by Arthur Bryant, 1932, 1979. AGD.......Reformation Society In 16th Century Europe by A.G.Dickens, 1966. AHJ....... Age of The Enlightened Despots 1660-1789 by A.H.Johnson, 1946. AMH......The History of The Jews In England by A.M.Hyamson, 1908. ANW......Hilaire Belloc by A.N.Wilson, 1984. AR..........Christians Courageous by Aloysius Roche. AWW......Pennsylvania by A.W.Wallace, 1962. BW.........The Whig Supremacy 1714-1760 by Basil Williams, 1939, 1974. CA..........The Jews In Poland by Chimen Abramsky, 1986. CCFE.....Cassell's Compact French-English Dictionary. CGB.......The English Presbyterians by ,1968. CH..........A History of The Jesuits by Christopher Hollis, 1968. COP.......William Penn by Catherine Owens Peare, 1959. CPA........The Jacobite Movement by Charles Petrie, 1959. CPB........The Stuarts by Charles Petrie, 1958. DCDA....English Historical Documents 1660-1714 by David C.Douglas, 1953. DCDB....American Colonial Documents To 1776 by David C.Douglas, 1962. DM.........Prince Eugene of Savoy by Derek McKay, 1977. DME......A History of New York State by David M.Ellis, 1967. DO.........England in Reigns of James II & William III by David Ogg, 1957. DW........Church and State In History by Douglas Woodruff, 1962. EB..........Encylopedia Britannica, 1995. EC..........The Framework of A Christian State by E.Cahill, 1932. ECA.......The Jacobite Challenge, edited by E. Cruickshanks, 1988. ECB........By Force or Default, edited by E.Cruickshanks, 1989. ECC.......The Political Untouchables edited by E.Cruickshanks, 1979. EJ...........Encyclopedia Judaica. FCT.......James II by F.C.Turner, 1948, 1950. FJP........The Reverend Richard Baxter Under The Cross by F.J.Powicke, 1927. FM.........The British Infantry 1660-1945 by Frederick Myatt, 1983. FSS.........Freedom of The Press In England 1476-1776 by F.S.Siebert, 1952. GBN.......Quakers and Politics In Pennsylvania by Gary B.Nash, 1968. GC..........The Late Stuarts 1660-1714 by Sir George Clark, 1955. GD..........Scotland: James V To James VII by G.Donaldson, 1965. GMT......English Social History by G.M.Trevelyan, 1942, 1946. GP..........The Thirty Years War 1618-1648 by G. Pages, 1970. GS..........Sacredness of Majesty by G.Gott (Royal Stuart Society), 1984 GWK.....Lord Chancellor Jeffreys & The Stuart Cause by G.W.Keeton, 1965. HAC......The Story of Britain by H.A.Clement, Vol. iii, 1943, 1962. HL.........Hansard (House of Lords), 20th July 1988. HALF....A History of Europe by H.A.L.Fisher, 1936. HB..........James II by Hilaire Belloc. HH..........A History of Modern Germany 1648-1840 by Hujo Holborn, 1964. HK.........The Rise of Toleration by Henry Kaman, 1967. HTJY.....History Today, July 1988. JC...........The Descent on England by John Casswell, 1989. JCA........Army, James II & The Glorious Revolution by John Childs, 1980. JH...........James II by Jock Haswell, 1972. JII...........The Anglo-Dutch Moment by Jonathan Israel 1993. JL...........The Plague and Fire by James Leasor, 1962. JPK........The Stuarts by J.P.Kenyon, 1958, 1977. JPKB......Robert Spencer, Earl Of Sunderland by J.P.Kenyon, 1958. JRJ.........The Revolution of 1688 In England by J.R.Jones, 1972. JRP.........The Non-Juring Bishops by J.R.Porter (Royal Stuart Society), 1973. KHDH....The Dutch in The 17th Century by K.H.D.Haley, 1972. MA..........James II by Maurice Ashley, 1977. MAB.......The Glorious Revolution of 1988 by Maurice Ashley, 1966. MDRL....Catholics in England 1559-1829 by M.D.R.Leys, 1961. MM........Mater Et Magistra by Pope John XXIII, 1961. MS..........The Persistent Prejudice by Michael Schwartz, 1985, 1986. MT.........The Shadow of The Cross by Meriol Trevor, 1988. NCE.......New Catholic Encyclopedia, 1966. ND..........God's Playground: History of Poland, Vol. I by Norman Davies, 1981. OAS.......Freedom From Fear by O.A.Sherrard. OC.........The Reformation by Owen Chadwick, 1964. PE..........Monmouth's Rebels by Peter Earl, 1977. PG..........The Age of Louis XIV by Pierre Gaxothe, 1970. PGR.......The Dutch in The Medway by P.G.Rogers, 1970. PH..........A Short History of The Catholic Church by P.Hughes, 1967, 1970. PMG......Louis XIV by Prince Michael of Greece, 1983. POD.......Pocket Oxford Dictionary. RC..........Christian Ethics and The Problems Of Society by R.Charles, 1974. RDG.......Huguenot Heritage by R.D.Gwynn, 1985. RDGB....English Historical Review Vol. xcii, pages 820-33, 1977. RH..........Louis XIV and Absolutism by Ragnhild Hatton, 1976. RJH........Christ Through the Ages by Robert J. Hoare, 1966. RRS.......Records Of the Royal Scots, Edinburgh. SEM.......A Concise History of The American Republic by E. Morison, 1983. SR...........The Plague and The Fire Of London by Sutherland Ross, 1965. TM.........History of England by Thomas Macaulay, 1848. VC..........Louis XIV by Vincent Cronin, 1965. WAS......Reluctant Revolutionaries by W. A. Speck, 1988. WE.........Notes on British History by William Edwards, 1955. WHL......The Splendid Century by W. H. Lewis, 1953.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||