|

The ChurchinHistory Information Centre www.churchinhistory.org

HITLER'S RISE TO POWER By

Part 1

'CHURCHinHISTORY' endeavours to make information regarding the involvement of the Church in history more easily available. CHAPTER I The Nazi party was formed in Bavaria and achieved its first electoral successes there. As Bavaria is considered to be the Catholic heartland of Germany, and Hitler was a baptised Catholic, it is sometimes implied that his movement grew out of a Catholic culture and took root amongst Catholics before spreading to the rest of the country. A survey of the anti-Catholic philosophical and political forces that gave birth to Nazism has been set forth in 'ChurchinHistory' publication 'The Roots of Nazism'. That publication established that few of the early Nazi leaders were Bavarian Catholics. They had come from other districts and religious backgrounds to congregate in the freer atmosphere of Munich. Here the growth of Nazism as a political party in Bavaria will be examined in more detail. During November 1923 Hitler attempted to seize Munich and use it as a base for a march on Berlin. He failed and spent 1924 in prison. His party was outlawed, and at two elections his supporters, together with others of like mind, stood as candidates of the 'Volkischer Block'. Due to the publicity surrounding Hitler's trial and imprisonment, these candidates gained a sizeable vote in Bavaria. By 1928 Hitler was out of prison and his party contested the November elections of that year under its own name. After 1928 Hitler obtained his highest percentages outside of Bavaria, so it is the two elections of 1924 and that of 1928 which need to be analysed. The results of these elections were as follows:

((GP 322-3))

'. . . in the May election of 1924 . . . outside Munich, the main areas paying heed to the Nazi message were already located in Franconia'. ((IK 23)). '. . . the majority of the Nazi party's 55,287 members in late 1923 were Protestants'. ((PDS 19)). This trend is illustrated by listing the results of these elections.

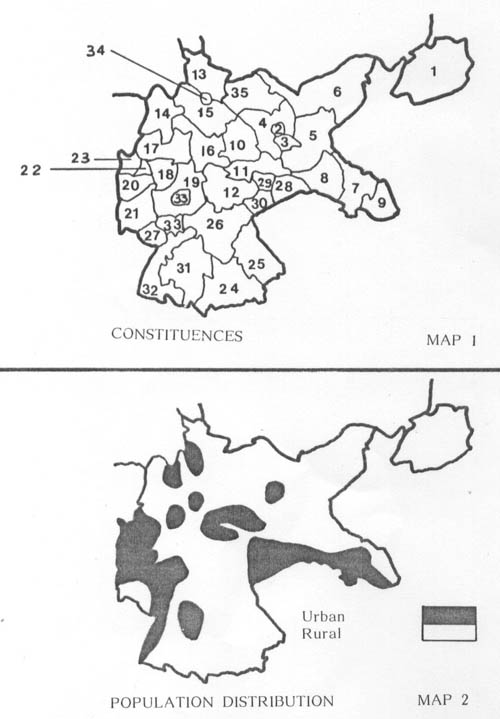

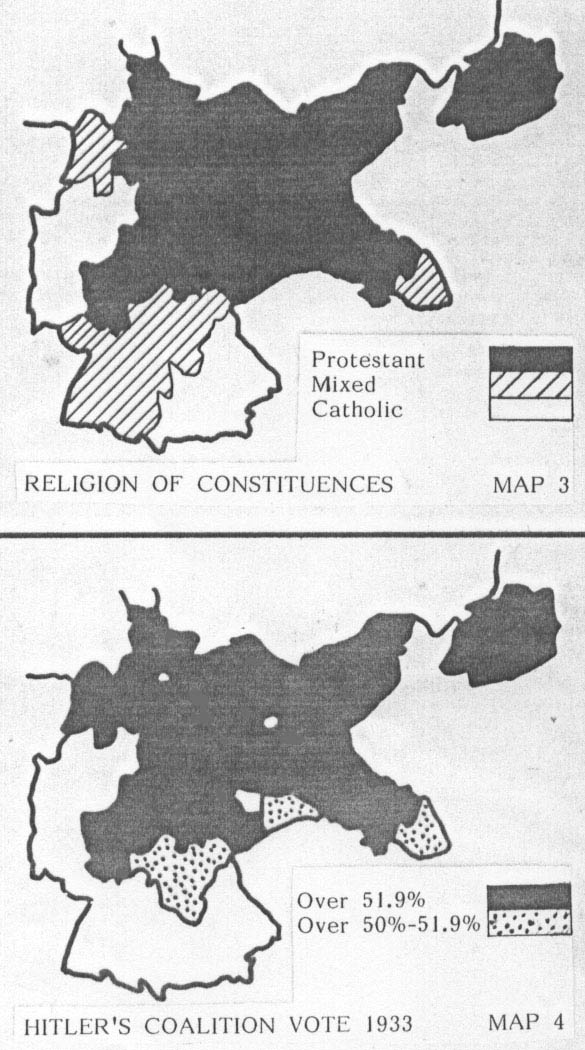

((GP 322-3 and EGR 84)). In some statistics 'Upper Palatinate' is not included as part of Bavaria, and this can cause slight discrepancies between figures. The high Volkischer vote in Catholic Upper Bavaria in May 1924 was due to their 28.5% vote in Munich. Although the city was 81% Catholic, religious practice was weak. This is indicated by the 36% who voted for the atheist marxist parties (Socialist and Communist), at that same election. Volkischer, Socialist and Communist adherence was able to grow amongst these lapsed Catholics. The Volkischer vote was also boosted by the mainly Protestant Borenhausen suburb, with its a traditionally high nationalist vote ((RFH 151)). In the more religious rural areas around Munich, Hitler gained little support, and even this was inflated. Germans could obtain 'Stimmscheine certificates' to enable them to cast their votes whilst on holiday, and many holiday makers cast their ballots in the tourist area of Upper Bavaria. Also, those holidaying in Austria could return to vote in villages along the border. For example, in the spa town of Garmisch, the registered electors in July 1932 numbered 19,700, yet 26,300 votes were cast. ((GP 284)). Research in Berlin indicates that Stimmscheine certificates were mainly applied for in the middle-class suburbs where nationalist feeling was strongest ((GP 285)). At a later date Hitler did gain a part of the Catholic rural vote, but this came to a great extent from former supporters of the Bavarian Peasants League (BBB). This was an economic interest group which fought the local state elections. It was mainly supported by baptised Catholics who were deaf to clergy exhortations. Immediately following the war the BBB was Communist led and its two leaders took part in the Munich Soviet Republic of 1918 ((GAC 407-8 and GP 70)). Later 'The Nazis swallowed up the BBB during the years of the depression' ((IK 20)). The Nazis also attracted a large proportion of young new voters ((GP 306)). It should be noted that 31% of Bavarian Catholics did not make their Easter Duties in 1931 ((GP 159)). There was another factor which promoted a high Nazi vote in Bavaria, compared with the rest of Germany. When Hitler was released from prison in 1924, he was banned from addressing large public meetings. This was lifted throughout Bavaria in March 1927, so he was able to hold rallies for 14 months prior to the May 1928 elections. In less stable northern Germany, the ban was not lifted till September 1928. The Nazi movement relied to such an extent on Hitler's unique powers of oratory, that its candidates were often specifically labelled as 'Hitler Movement' ((EBW 90)). This situation contributed to the low Nazi vote in northern Germany, where Hitler was comparatively little known at this time. It is sometimes asked why the Bavarian authorities failed to control Hitler during his early years. But in 1922, the Catholic Bavarian Minister of the Interior proposed to deport Hitler to his native Austria, and face the outrage of the Nazis and Volkischer groups. The plan had to be abandoned when the Socialists opposed what they considered to be an infringement of free speech ((EBW 58)). Further attempts failed because the Austrians did not want him back. As Hitler had served in the German army, he persuaded the Austrians in April 1925 to annul his citizenship and he became stateless. In 1932 Hitler wished to stand as a Presidential candidate and needed German citizenship to qualify. The state Government of Brunswick, which was a Protestant state, provided him with a nominal official position so as to solve his problem ((EBW 118)). The image of Catholic Bavaria being a stronghold of Nazism, was enhanced by its second city Nuremburg becoming associated with Julius Streicher's first 'Storm Troopers' and the mass Nuremburg rallies. Because of the symbolism of this city for Nazism, the war crimes trials were held there after the 1939-1945 war. Yet, as the city was 62% Protestant, it was not typical of Bavaria. The first town in Bavaria to give the Nazis a majority on its municipal council was 90% Protestant Colburg in June 1929 ((GP 85-6)). Hitler was well aware of the situation. In 1925 he forecast that his Movement would eventually be strongest in the north of Germany, but insisted that its Headquarters should stay in Bavaria, where the opposition was fiercest ((GP 46)). CONCLUSION A close look at Bavarian politics shows that its Catholic culture inhibited the growth of early Nazism. The movement took hold in the minority non-Catholic segment of the Bavarian population, aided by some lapsed Munich Catholics who had rejected their upbringing. CHAPTER II BACKGROUND The 1925 census showed Germany as 63% Protestant; 32% Catholic; 1% Jewish and 4% other beliefs. Catholics were strong in the south and north west and there were further Catholic pockets in Silesia and East Prussia (See Map). Prior to the 1914-18 war, the Kaiser (King) ruled with the Reichstag (Parliament) acting in an advisory capacity. The four main parties were: Nationalist (DVNP): authoritarian, conservative and nationalistic. Conservative (DVP): democratic, conservative, nationalistic. Liberal (DDP): democratic and emphasising personal freedom. Socialist (SDP): marxist at core but wishing to obtain its aims by popular consent. The Catholic Church was critical of these parties because :

The Liberals and Socialists wished to undermine the right of parents to send their children to Church schools. The Church supported the Centre Party because :

Between a half and three quarters of the Catholics voted for the Centre Party. The others did not necessarily support the philosophy and long-term aims of the non-Catholic parties, but either felt the Centre was too keen on social reform to be able to protect middle-class interests, or felt that it was not militant enough to obtain quick social improvements. THE END OF THE WAR By 1917 the warring countries were exhausted and the outcome was still evenly balanced. The Pope proposed a peace plan:- Germany to withdraw from France and Belgium; the Allies from the German colonies; all countries to reduce arms simultaneously, territorial disputes to be settled in a conciliatory spirit; and neither side to demand reparations ((JOS 46)). As most of the fighting had been on French soil, the French demanded reparations. Germany refused as this would imply that she was guilty of causing the war. It was pointed out to France that by ending the war quickly she would be saving the north of her country from even more destruction. France also wanted the return of Alsace-Lorraine which she had lost in 1870. The Kaiser refused to accept the Pope's proposal for Germany to withdraw from Belgium. When the war had started, the Kaiser stated that Germany was not embarking on a war of conquest, but to defend her freedom ((JR P M 13)). It was on this understanding that the Centre, Socialists, Liberals and, others, had given their support to the war. But now the Kaiser would not accept the proposal to withdraw from Belgium. On 19th July 1917, Erzberger, leader of the Centre, proposed a "Peace, Resolution" in the Reichstag: "The Reichstag strives for the peace of understanding and permanent reconciliation of peoples. Forced territorial acquisitions and political, economic and financial oppressions are irreconcilable with such a peace" ((GAC 387)). This was, in effect, a proposal to withdraw from Belgium. With Socialist and Liberal support the resolution obtained 212 votes against the 126 of the Nationalists and Conservatives. There were 17 abstentions ((WF 116)). On the 14th of August, the Pope officially presented his proposals to each country. But the Kaiser, who possessed greater constitutional power than the Reichstag, still refused to withdraw from Belgium, and France insisted on her demands. So the war continued for another year until the Kaiser accepted it was lost. On September 28th 1918 he transferred power to the Reichstag. Those parties which had passed the 'Peace Resolution' would now take the blame for 'surrendering', not he, the army nor the Nationalists. The years following were traumatic times of inflation, massive unemployment, poverty, political violence, and a profound sense of national weakness, disunity, bitterness and humiliation. The Nationalists and Conservatives blamed all this on the 'Peace Resolution' parties. The Catholic Centre party was particularly hated and Erzberger was assassinated. Soon after the end of the war, some members of the Socialist party broke away to form the Communist Party, which aiming to achieve a marxist state by revolution and dictatorship. During the same period the Bavarian section of the Centre Party detached itself to form the Bavarian Peoples' Party (BVP). The result of the Presidential election of 1925 gives an indication of the political situation at that time. As no candidate received 50%, a second ballot was held. The Nationalist candidate in the second ballot was Hindenburg, who was elected. He did not believe in democracy, but was willing to accept it as preferable to civil war.

THE SUDDEN NAZI GROWTH Since 1918 the Centre, Liberals, Socialists and sometimes the Conservatives had formed coalition governments. But the economic crisis of 1929, together with Communist pressure, led to a Socialist refusal to take part in further coalitions. As the Liberals feared losing votes to the Conservatives, they also withdrew ((GAC 532 and JRPM 210)). On 28th March 1930, the Centre's leader, Heinrich Bruning formed a government with less than 16% of Representatives supporting him. These were those of the two Catholic parties, the Centre and the Bavarian. The President had to use his emergency powers to put legislation into effect. Following the elections of 14th September 1930, Bruning's Catholic Parties continued to run the country. In these latest elections the Nazis had gained a surprising 18.3% of the vote. THE CATHOLIC REACTION Immediately after these elections, in which the National Socialist Party had emerged as a major force, the bishop of Mainz excommunicated all Catholic members of the party in his diocese, and banned uniformed groups entering churches ((KG 12 and A R 166)). He also gave instructions that party members would not be allowed to take an official part in funerals and other services ((RD 8, 9 and 12)). The other bishops decided to await the annual bishops' Conferences, so as to be able to formulate a united policy. In Rome the Osservatore Romano of October 11th 1930 commented: "Belonging to the National Socialist Party of Hitler is irreconcilable with the Catholic Conscience." In his New Year message, Cardinal Bertram of Breslau condemned extreme nationalism, without specifying the Nazi Party ((KG 13)). The National Socialist challenge to the Church took a different form to that of the marxist parties. Their anti-religious philosophy and programmes were clearly set out, but Hitler's party was not so specific. Pagan, anti-Catholic and anti-religious books and speeches were explained away by claiming that they were the views of individuals. In this manner the Nazis tried to gain the support of anti-Catholic and anti-religious people, without alienating churchgoers. It was said that Hitler had modified the pagan views which he had set forth in ' Mein Kampf'. The Nazis repeatedly claimed that they were defending Christianity from godless marxism, and could have good relations with the churches provided the clergy kept out of politics. The hierarchy's annual Conferences were held at Fulda and Freising during February 1931. They endorsed the action of the bishop of Mainz, but said that a distinction should be made between 'Activists' and 'Followers'. This was because some Catholics had voted for the Nazis because of their foreign policy, or in the hope that they would cure the economic situation and reduce unemployment, while not realising the party's long-term pagan aims. Such a distinction had already been made with regard to the Socialist and Communist parties in 1921. The attitude of the bishops since 1924 regarding extreme nationalist groups had also drawn this distinction ((KG 14 and GP 167)). To implement their decisions the bishops decided to: 1. Issue Pastoral Letters addressed to all the Faithful. 2. Send a letter to the clergy giving guidelines for distinguishing between 'Activists' and 'Followers'. 3. Take steps to isolate certain rebel priests who held views favourable to the National Socialist Party. The Pastoral Letters were sent out during the following weeks ((KG 13)). That of the Bavarian hierarchy, issued on February 10th, was typical. It condemned National Socialism because: "It puts race before religion; rejects the Old Testament including the Ten Commandments; denies the authority of the Pope because he is outside Germany; plans a national church; puts the 'moral feelings of the German race' as the criterion of all morality". ((BS 807, RD 8, 9 and 12)). It continued by pointing out that in their speeches, Nazi leaders had rejected the Concordats made with the local states, attacked denominational schools, called for the repeal of the laws which protected unborn life, and advocated a radical nationalism ((BS 807)). Whether a supporter of this Movement would be permitted the Eucharist, had to be judged on an individual basis. There was a difference between a person who had voted for the party without realising its pagan philosophy, and an elected representative, a writer, or an agent of the party ((BS 808)). Even here, pastors were very reluctant to refuse the sacraments to a person who, though an active member of the party, rejected its basic Nazi philosophy. Some people were muddled and short sighted rather than heretical. Some believed that the pagan elements would lose their influence once the party was in power. The bishops considered that the few priests who had written pro-Nazi articles had no excuse as they were educated enough to see that Nazism was contrary to Christian doctrine. These priests were therefore isolated ((KG 14-5)). During the following two years a continuous campaign was waged, through pulpit and press, to expose the ultimate aims of the Nazi Party. The Nazis replied, that the church was led by 'political bishops’, supporting the Centre Party under the cloak of religion. It is impossible to quantify the effect of these condemnations. Most Nazi activists were already far from the Church in their life-styles and beliefs. Most of their followers, especially after the Pastoral Letters, were not practising Catholics. There would have been an effect on those pious Catholics who took little interest in politics and, without the condemnations, may have been deceived into voting for Nazi candidates. At the same time, militant Catholics were spurred into increasing their anti-Nazi activities. The Centre Party vote stood very firm against Nazi allurements. In March 1933, the Centre's vote rose although, due to the greater number of people taking part in that election, its proportion of the vote fell. THE END OF DEMOCRACY The Presidential election in the Spring of 1932 found the democratic parties too weak to offer a candidate. So they supported Hindenburg in order to keep out Hitler and the Communists. He was still willing to work within the democratic constitution. As no candidate won 50% of the votes, a second ballot had to be held.

So 47% had voted to abolish Democracy. Hitler, a renegade Catholic, found his main support in Protestant areas, while the staunchly Protestant Hindenburg found his in the Catholic areas. For example:

((EBW 118-120)). So a majority of Protestants had rejected democracy by April 1932 As the other democratic parties refused to shoulder governmental responsibilities, Bruning continued to rule with his Centre Party. The Socialists 'tolerated' him (i.e. they abstained on 'no confidence' votes). Municipal elections showed a continuing rise in Nazi support, and the only way Bruning could halt it was to achieve, by peaceful diplomacy, what Hitler said could only be achieved by force. These were: 1. A Customs Union with Austria (which Austria desired).

2. Cancellation of war reparations. Because of French opposition, the first objective could not be achieved, but by the end of 1932 Bruning had succeeded with the other two. The delay however had fuelled the impatience, frustration and anger upon which Hitler depended ((WC 318-20)). Bruning was also dealing with grave internal problems. He banned the Nazi SS and SA para-militaries, while leaving the more peaceful Socialist para-militaries alone. He drafted plans to resettle 600,000 unemployed people from western Germany on large underused estates in the east. He started a public works program to ease unemployment ((WC 318-20)). The landowning leaders of the Nationalist Party were worried regarding their estates and the one-sided banning of the para-militaries. So, aided by the influence of the army, they persuaded the President to dismiss Bruning. 'The fall of Bruning was a real turning point . . . he was one of the great figures produced by the Weimar Republic . . . who guided Germany through the worst phase of the depression. Once he had departed . . . the accession to power of the Nazis was only a matter of time' ((WC 318-20)). Franz von Papen was appointed to replaced Bruning as Chancellor and, as he was a Catholic, he is often portrayed as typifying a new Catholic attitude to Hitler at this time. Sometimes he is said to have been the leader of the Centre Party. These views are false. At one time he had been an extreme conservative rebel member of the Centre Party in the Prussian local parliament. But when he agreed to become Chancellor, he neither held a seat in the Reichstag nor in a local parliament, nor any office within the Centre Party. When he became Chancellor the Centre Party expelled him ((JRPM 230)). For more details of his life see Chapter IV. In the July 1932 Reichstag elections the Nazis polled 37.3%, the Communists 14.3% and the Nationalists 5.9%. The Conservatives, Liberals and smaller parties nearly disappeared. The vote for democracy was down to 42.1% On 17th August the Catholic bishops warned of 'the dark prospects' for the Church if Nazism prevailed ((KG 15)). In the Reichstag election of the following November the democratic vote fell to 41.7 %. Papen wished to ban both the Nazis and the Communists but, as the army did not consider itself strong enough to fight both of them at the same time, this was not possible. General Schleicher formed an administration for a short period but was not able to solve the mounting problems. So on 30th January 1933, a coalition government was formed with nine Nationalist and two Nazi ministers. Hitler became Chancellor (Prime Minister) and Papen his deputy. Papen was convinced that the President, big business, parliament, the army and his own skill, would be able to control Hitler until his popularity waned. The Nazi vote was starting to fall in local elections ((KCA 578)) and Papen told a friend, "In two months we'll have pushed Hitler into a corner so hard that he'll be squeaking". ((WC 325)). A Papen supporter said "We have Hitler framed in" ((GAC 568)). Papen's Nationalists were not a totalitarian party but wanted authoritarian rule without racist and other pagan Nazi ideas ((FVP 268)). Papen was not alone in thinking that Hitler's power was on the wane. The "Worker's Newspaper" of the Austrian Socialist Party proclaimed 'Hitler could wait no longer. Every day made him weaker. He chose the other eventuality: the Chancellorship, in truth, surrender.' ((FW 72)). Most political leaders, including those of the Centre Party, did not think that Hitler would last long ((FVP 251)). Although the new Nationalist-Nazi government had 43% of the seats, it still did not command a majority. Despite pressure from the President, the Centre refused even to 'tolerate' it. The President ordered fresh elections for the 5th of March in the hope that the new coalition would gain a majority of seats so as to be able to administer the country in a stable manner. He announced that: "He wished to ascertain the attitude of the German people to the new government, which at the present hasn't a working majority" ((KCA 656)). This came very close to him openly asking the electorate to vote for Nationalist and Nazi candidates. On the 27th February the Reichstag building was burnt down and, by using forged documents ((FVP 269)), Hitler convinced the President and Cabinet that there was a Communist conspiracy to seize power. The following day, the President issued a decree granting the government emergency powers. This decree remained in force until 1945. The decree stipulated: 1. Suspension of all the basic rights of the citizen. [This was an unlimited power of arrest, interrogation, imprisonment, searches, phone tapping, censorship, and authority to ban meetings, organisations and publications]. 2. Authorised the Reich government to assume full powers in any federal state whose government proved unable or unwilling to restore public order and security. 3. Order death or imprisonment for treason, assault upon a member of the government, arson in public buildings, incitement to riot, and resistance to the provisions of the decree. Although Hitler had become Chancellor, the Nazis still formed a minority within the Cabinet. But the support for the Nazis in the country and their seats in parliament dwarfed that of their coalition allies. They were therefore able to claim the key Ministries they wanted. The decree gave the government, which was soon to become dominated by Hitler, dictatorial powers. It meant that any act or word of opposition to the government's Will, could result in the imposition of the heaviest penalties. The decree was the legal basis upon which the Concentration Camps were established ((GAC 574-5)). The decree was not limited in any way, so Ministers could interpret it as they wished. An arrested person had no right to a prompt hearing, counsel, appeal or redress for false arrest ((GAC 574-5)). The decree 'was the fundamental emergency law upon which the National Socialist dictatorship . . . was primarily based'. It was more important than the later Enabling Act of March 24th ((EB 200)). The Nazi dictatorship had begun ((WC 326)). If the coalition could obtain a majority in a free election, Hitler would become the dictator of Germany in a legal and democratic manner. HITLER IN POWER Hitler permitted the 5th of March elections to proceed. He knew that if he won it would deal a serious psychological blow to his democratic enemies and facilitate his assumption of full power. If he lost he could use the Emergency Decree to arrest enough opposition Representatives in order to provide his government with the majority it required. A Government spokesman assured the foreign press that the days of parliamentarianism and democracy were definitely finished in Germany. An entirely new regime had come, and come to stay ((KCA 692)). Although the decree was used to interfere with the freedom of the press and radio in Prussia and to close some Centre and Socialist meetings, the vote was secret. Hitler's dictatorial and often brutal methods did not lose him votes, but seem to have drawn him support from people desperate to elect a firm, strong and united government, with a clear majority, which would solve the country's problems in a speedy and efficient manner. This election gave the electorate the opportunity to show whether they agreed with the Emergency Decree and the way Hitler was using it. A very high poll of 88.5 % gave its verdict:

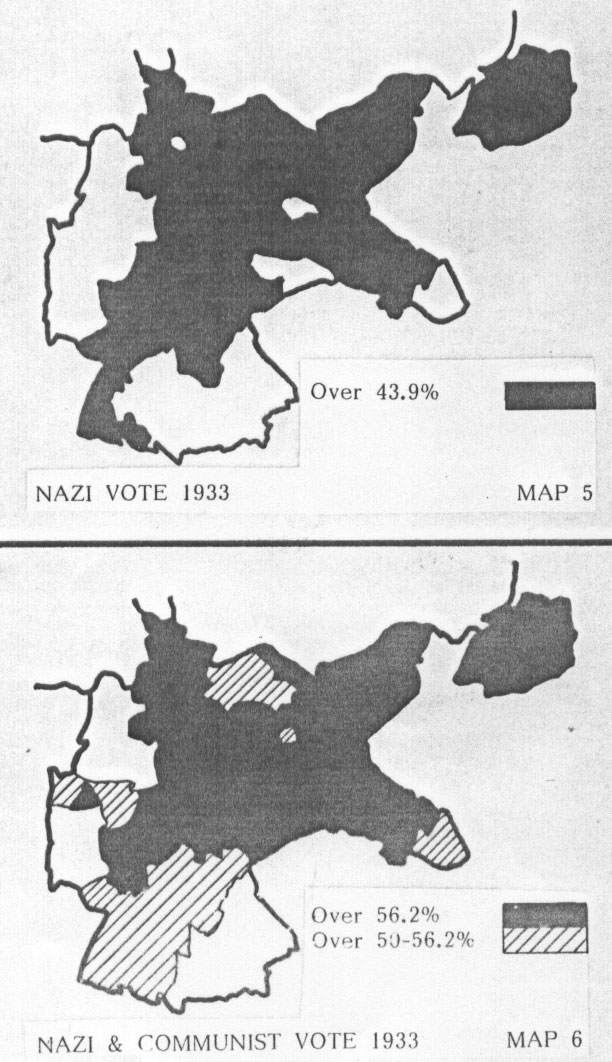

The 35 electoral districts may be classified into 21 Protestant, 7 Catholic and 7 mixed. The Nazis achieved over 50% of the vote in 7 constituencies, all strongly Protestant. When we include the Nationalist vote we find that the coalition gained over 50% in 20 constituencies (13 Protestant, 3 mixed and none Catholic). In only 6 constituencies was the combined anti-Democratic totalitarian vote (Communist and Nazi) less than 50%. Five of these were Catholic and one mixed. Soon afterwards a judgement on Hitler's rise to power was made by the Nazi paper, 'Volkischer Beobachter' of 29th March 1933: "The first and fiercest adversaries of the new party were parliamentarians of the Centre. The Church leaders followed them." ((RD 71). This closely echoed what Hitler had written nine years previously in 'Mein Kampf' regarding the earliest years of nazism: " . . . in these very years, the movement carried on the bitterest fight against the Centre . . ." ((AH 514)). Following the result, a wave of National Socialist enthusiasm swept all before it. Thousands of former opponents now wished to be on the winning side and joined the Nazi party ((GAC 577)). Others joined because they were willing to accept their fellow voters' democratic verdict or had a sense of foreboding. The Socialist para-military force decided not to fight, as they feared it might end in a blood-bath ((GAC 664)). Whole units deserted to the Nationalist Party's Stahlhelm, which also recruited amongst former Communists ((KCA 732-4)). The A.D.G.B. (National Trade Union Federation) announced its willingness to break its ties with the Socialist Party and co-operate with the new government ((GAC 576)). Membership of the Socialist Unions fell by about a third in one month ((KCA 778)). Sir Walter Citrine explained to the British Trade Union Conference that, as 63% of Germans had voted for dictatorship, the Socialists had refused to call a general strike because it would have led to a civil war ((TT 8 Sept 1933 page 18)). Within two weeks, Centre and Socialist controlled local parliaments and municipal councils had been replaced by Nazi officials ((KCA 709)). Hitler wished to keep within the letter of the law. So, rather than arbitrarily dissolve the Reichstag, he demanded that an Act be passed enabling him to rule for four years without having to refer to it. This would involve a change in the Constitution, requiring a two-thirds majority. An 'Enabling Act' was proposed in the Reichstag on March 23rd. Hitler said that he did not want Socialist votes ((JRPM 231 and WLS 199)), so concentrated all his threats and promises on the Centre. At the end of his speech he said: "The Government will regard its rejection as a declaration of resistance. Now, gentlemen, you may yourselves decide for peace or war" ((KCA 726-7)). Under the Emergency Decree 'resistance to the government' could be interpreted as resistance to the decree, and therefore punishable by any penalty including death. Outside the building the SA and SS had placed a cordon, and the air was filled with "Ermachtigungsgesetz . . . Sonst gibt's Zunder!" [We demand the Enabling Act . . . or there will be an explosion!] ((GAC 577)). Goering, a Nazi leader, had stated on March 15th that if necessary they would eject some of the Socialist deputies so as to obtain a 2/3 majority for the Decree ((EBW 257)). The Cabinet had agreed that deputies absent from the vote would be counted as in favour ((EBW 259)). The Centre, M.P.s were divided as to what to do, bearing in mind that only 36% of the Germans desired parliamentary democracy. Kaas, their leader, argued that if Hitler did not get what he wanted by means of the Act, he would secure it by more unpleasant means and that it would be wiser to concede and hope for favours in return ((GAC 578)). Others wished to make a symbolic gesture of defiance. Eventually the majority accepted the view of Kaas. Fear and a sense of the hopelessness can be seen in their final statement. "In view of the storms which threaten to arise in and about Germany, the Centre would set on one side the doubts which in normal times could not be overcome, and would vote for the Bill" ((GAC 578 and KCA 726-7)). 107 Communist and Socialist M.P.s were missing because of arrest or intimidation. The remaining Socialists voted against and, like the Centre's leaders, had to flee from the country within a few months. THE CHURCH After gaining power, Hitler continued to maintain that he was not opposed to the Churches and wished them to work with him. He claimed that he was a victim of 'political bishops' who still aimed to wield power through the Centre Party. When the Reichstag met on March 21st, the Catholic Representatives attended a special Mass at Potsdam. Hitler, who had been baptised a Catholic as a baby, issued a statement: "The German Catholic bishops have quite recently, in a series of public declarations on which the clergy have not hesitated to act, stigmatised the leaders of the National Socialist Party as traitors who should be refused the sacraments. These instructions have not been withdrawn and are still being carried out. In these circumstances the Chancellor is reluctantly compelled to remain away from the Catholic service at Potsdam. During the celebration the Chancellor and the Propaganda Minister, Dr. Goebbels, placed wreaths in the Luisenstadt cemetery in Berlin on the tomb of their murdered comrades of the Storm Troops." ((RD 72-5)). This was hypocrisy. At this time, Nazi Party members were excommunicated, and neither Hitler nor Goebbels had been practising Catholics. Both had completely rejected Catholic teaching. The statement was nothing more than a propaganda move to put the responsibility for Nazi-Catholic hostility onto the shoulders of the bishops. When demanding the Enabling Act, two days later, the government declared: "The National Government regards the two Christian confessions as factors essential to the soul of the German people. It will respect the contracts they have made with the various regions. It declares its determination to leave their rights intact. In the schools, the government will protect the rightful influence of the Christian bodies. We hold the spiritual forces of Christianity to be indispensable elements in the moral uplift of the German people. We hope to develop friendly relations with the Holy See". ((RD 72-5)). This provided a little hope that, now that Hitler had the responsibilities of power, he might give priority to establishing national unity and the implementation of his economic and foreign policies, rather than cause national dissension by trying to impose a pagan racist creed. Thousands of Catholics now found it necessary to belong to the Nazi party, or one of its workers' organisations, in order to keep their employment in the Civil Service and local government. The bishops responded to this new situation by permitting party members to receive the sacraments and have a religious burial ((RD 72-5 and EBW 281)). Apart from easing the position of Catholic Civil Servants, this move was also a gesture to encourage the government to adhere to its protestations of friendship towards the Churches. It was difficult to foresee which elements within the party might come to dominate. A statement issued by the bishops assembled at Freising, read: "As long as the leaders of the National Socialist Party can maintain towards the Church the benevolent attitude expressed in the declaration of the Chancellor, the bishops for their part will remain faithful to the point of view now indicated. It is unnecessary to add that this episcopal edict is in no sense an invitation to join the National Socialist Party, especially as the bishops have formally signified the continuance in force of the condemnations already passed on certain religious and moral errors". ((RD 72-5)). The Church had done her utmost to prevent the Nazis becoming the Government of Germany. But now the party was the legal government, the bishops had to accept it while fighting Nazi ideology by different means. PRAISES OF HITLER The words of individuals are sometimes quoted as 'evidence' of Catholic enthusiasm for Hitler. But these utterances must be read within the context of the times. During the first years of his rule, many hoped that Hitler would use his unique gift of leadership to improve Germany's situation while letting the pagan aspects fall into the background. The French ambassador to Germany, M. Francois-Ponet, wrote at the time of the Berlin Olympic Games in 1936: "Hitler's extraordinary personality has imposed itself on Europe. He does not merely rouse fear or aversion; he excites curiosity and awakens sympathy. His prestige increases; his magnetic attraction is felt beyond the frontiers of Germany. Kings, princes and other illustrious guests throng the capital of the Reich, less perhaps to take part in the approaching Games than to meet the prophetic figure who appears to hold the destinies of our continent in his hand, and see at close quarters that country, which his irresistible grasp, has transformed and galvanized. All are enraptured by his faultless organisation, his perfect order and discipline, as well as his boundless prodigality" ((NP 98)). Winston Churchill wrote in 1935, and allowed to be published in 1937: "It is not possible to form a just judgement of a public figure who has attained the enormous dimensions of Adolf Hitler, until his life-work as a whole is before us . . . men have risen to power by employing . . . .frightful methods but . . . when their life is revealed as a whole, have been regarded as great figures whose lives enriched the story of mankind. So it may be with Hitler". (See longer extract in Chapter XI). In 1936 the British Liberal leader, Lloyd George, met Hitler and said how honoured he was to receive a gift from "The greatest living German". Hitler is: "The George Washington of Germany" (See ChapterXI). The British Labour Party opposed rearmament up till July 1937, because it did not believe that Hitler was a threat ((DT 178)). Ernest Bevin, a Labour leader, admitted in 1941: "We all refused absolutely to face the facts". ((DT 178)). In September 1938 Hitler, speaking of the Sudetenland, said "This is the last territorial claim I shall make in Europe" ((DT 175)). The British and French governments accepted his word. So it is not surprising that in the first few months of Hitler's rule, while he was full of assurances towards Christianity, world peace and justice, that many Germans assured him of their support for his political and economic aims. Catholics, including bishops, assured the government of their loyalty to Germany and willingness to co-operate in building a dignified and prosperous country under its democratically elected leader. By being co-operative they hoped to increase their influence and so encourage the moderate elements within the Nazi Party. It is from this short period that quotations from responsible Catholics, pledging support, may be found. The very fact that in the election campaign they had used such strong language to condemn Nazism, meant that they also had to be emphatic when stating that they accepted the nation's verdict and would be loyal to Germany and its new democratically elected popular leader. THE CHURCH CONTINUES THE FIGHT While accepting the legality of the Government, the Church did not relax her fight against the pagan elements within the Nazi programme. During the second half of 1933 the bishops issued repeated statements and Pastoral Letters against Nazi ideology, infringements of liberty and contravention of the Concordat. These, and those of the next few years, need a book to list them. Many may be read in 'The Persecution of the Catholic Church in the Third Reich' ((CBC)). Starting in October 1933 (within weeks of the Concordat being ratified) the Pope, speaking to a group of German visitors, vehemently supported their struggle to defend Christianity ((CBC 1)). On May 6th 1935 he said "In the name of so-called 'Positive Christianity' efforts are being made to de-Christianise Germany and lead her back to barbarous paganism" ((CBC 5)). At Christmas 1936, while speaking of the Spanish civil war, then being fought, he attacked the hypocrisy of the Nazis claiming to be leading the defence of Christian values ((CBC 6)). On 14th March 1937, four years after Hitler's Reichstag speech promising religious freedom, he issued the Encyclical 'Mit Brennender Sorge', in which he strongly condemned the whole pagan racist creed and its imposition on Germany. It was sent secretly to all parish priests and read from the pulpits throughout Germany on the same Sunday morning. The success of this tactic, which prevented the authorities confiscating copies, indicates how united and defiant the hard core of Catholics had become. The Americans, especially the large numbers of German descent, admired Hitler's achievements in regaining Germany's international status, building economic prosperity and fighting Communism. Many accepted Hitler's claim that there was freedom in Germany except for agitators and political clergy. But on May 18th 1937 the American Cardinal Mundelein, said during a speech in Chicago: "Perhaps you will ask yourselves how it is that a nation of sixty million intelligent persons bows in servile fear before a foreigner, and a fool into the bargain, and before two scoundrels like Goebbels and Goering," who claim to regulate the slightest details of the people's life". ((NP 95)). The enormous publicity the speech received caused the German government on May 24th to protest to the Vatican most vigorously. Cardinal Pacelli, Secretary of State, replied that when the persecution stopped he would look into the affair. A further protest on the 29th resulted in Cardinal Pacelli despatching a note, on the 24th June, to the German government praising Cardinal Mundelein ((NP 95-6)). President Roosevelt, taking advantage of the atmosphere, visited Chicago on October 5th and also vehemently attacked Nazi Germany ((NP 98)). In the following November the American bishops issued a public letter of support of the German Catholics in their suffering ((NP 93)). There had been a strong feeling in America that she should not become involved in European conflicts, but the anti-Nazi campaign of the American Catholic bishops contributed to making it possible, two years later, for the President to assist the Allied cause even though not at war. Also in 1937, Pope Pius XI issued the encyclical 'Divini Redemptoris', which was a condemnation of Communism. The Pope was well aware that the Nazis would use its publication for propaganda purposes, as they claimed they were the only effective defence against Communism. To prevent this it was not published until March 19th, by which time it was known that 'Mit Brennender Sorge' had been successfully read five days previously in Germany ((NP 86)). Four months later at the Nazi Party's Nuremburg Conference, the "National Prize" was awarded to Alfred Rosenberg, thereby making his pagan 'Myth of the Twentieth Century', the official teaching guide of the new Teutonic religion ((AR 214)). Following the Encyclical, the battle between the Church and Nazi ideology was intensified. CHAPTER IlI CHART A THE ANTI-DEMOCRATIC VOTE IN MARCH 1933

CHART B Percentage of votes received at each election, with the last column showing the change between 1928 and 1933 for each party.

NOTES 1. For location of Constituencies see Map No. 1 2. A * sign on Chart A indicates Constituencies with a high Communist vote (over 17%). Their highest vote was in Berlin (30.1%). 3. A ^ sign on Chart A indicates highest vote, v indicates the lowest, in the list. 4. Religious allocation of constituencies, and map indicating areas of high population density, are based on 1925 census. 5. Charts and maps based on 'Wahler and Wahlen in der Weimarer Republik'. Published in Bonn, West Germany, 1968. Detailed maps, showing relation of the Nazi vote to religion, may also be seen elsewhere ((eg. KG end page)). 6. Elections were by proportional representation, so seats held in the Reichstag closely mirrored votes received by each party. 7. The Nationalists wished for rule by a powerful President, who would listen to, and often take the advice of, a freely elected Parliament. They were not totalitarian as were the Nazi and Communist parties. 8. The only constituency in 1933, to vote for the continuance of the Weimar democratic system was mainly Catholic Lower Bavaria. 9. All the Protestant constituencies had clear majorities for totalitarian (Communist and Nazi) parties. The two constituencies in the Catholic areas that voted that way did so by narrow majorities of less than 51%. 10. The vote for the Catholic patties rose in 1933, although the high poll caused their percentage to fall. This indicates that the Nazi vote in Catholic areas was drawn mainly from those who normally supported non-Catholic parties (i.e. the non-Catholic minority, lapsed Catholics and those who lacked wholehearted loyalty to their Faith and Bishops). 11. During Hitler's rise to power the Protestant right-wing and Liberal parties lost 72% of their vote share, the Socialists 38% and the Catholic parties 9 %. 12. Catholic rural and urban areas both rejected the Nazis and Hitler's coalition. THE UNIVERSITIES Due to the stronger Catholic presence at Freiburg and Munich, the Nazis polled only 25% ((PDSA 62)) and 33% ((GP 210)) respectively. At Bonn, where Catholics were 57%, the Nazis schieved 19% ((GP 211)). The Nazis failed at Wurzburg until there was '... an influx of Protestant students from Prussia . . .' ((PDSA 63)). The Socialists and Republicans were strong in Protestant Hamburg, but poor organisation led to a Nazi victory ((PDSA 63)). The situation has been summarised as, 'The vote for the NSDStD was generally much stronger at Universities where the large majority of students were Protestants'. ((GP 210)).

NAZI CARTOONS At first attacks were

made against `political` sections of the Church, while friendship was professed to those Catholics `loyal to Germany`.

After the 1937 Encyclical, the Church herself was accused of supporting Jewish Communist plots against Germany.

Cardinal Pacelli became Pope Pius XII twenty months later. The first cartoon is from: `Das Schwarze Korps, July

22nd, 1937. Humanité was a Communist newspaper. The

second from: `Der Heidelberger Student, May 4th, 1935. It

shows a Nazi exposing Jews, Jesuits and Freemasons plotting together.

CHAPTER IV It is widely asserted that, who was instrumental in bringing Hitler to power, represented Catholic political opinion. It is sometimes stated that he was the leader of the Catholic Centre Party. Yet both these assertions are false. Born in 1879, Von Papen was a Westphalian aristocrat with industrial connections. He was a Catholic and a former General Staff officer in the old Prussian army. Following the 1914-1918 war, he returned to Westphalia and purchased a large farm. His neighbours asked him to stand for the Prussian state parliament to represent farming interests. He agreed but did not join the Conservative Party, which in many ways came closest to the views of the farm owners. He later wrote: 'The Conservatives had too much prejudice and too many obsolete ideas' ((FVP 97)). He joined the Centre Party because most of the electors in his constituency were Catholics and it was devoted to compromise and the solving of social problems. ((FVP 97)). In 1924 he was elected as a Centre Party M P to the Prussian state parliament ((FVP 103)). This local parliament was not restricted to the historic area of Prussia, but covered much of northern Germany. As in the national parliament, the Centre had formed coalitions since 1918 with the Socialists and Liberals. Papen immediately urged the Centre to break with the Socialists and form a government with the Conservatives. He was not successful and when the new coalition ministry was presented to parliament he led five other Centre MPs into voting against their own party's nominees. Because of his influence in bringing the farming vote to the Centre, he was not expelled ((FVP 106)). He was, however, banned from all committees, and became known as the 'black sheep' of the party ((FVP 106)). In his Memoirs he wrote that his controversial position in the Centre was further complicated when he purchased 47% of the shares in 'Germania', the principal mouthpiece of the Centre Party ((FVP 111)). This 'caused consternation at party headquarters'. Papen became chairman of the Board of Directors and dismissed the editor and manager. He promised, however, to allow freedom of expression to all sections of the party. Trade Union leaders and a bishop were appointed to the board so as to balance Papen's conservatism ((FVP 111)). In April 1925 the Centre put Dr. Wilhelm Marx forward as their candidate for President. Dr. Marx also had the support of the Socialists and Liberals, but Papen campaigned for Hindenburg, the Conservative and Nationalist candidate, claiming that voting for a President should not be considered a party matter ((FVP 107-8)). Papen later wrote 'This episode naturally made my position in the party extremely difficult, I had become an outsider . . .' ((FVP 107-8)). Just prior to the 1932 elections, the Centre, Socialists and Liberals changed the method of electing the Prussian Prime Minister. This was to make it more difficult for a Nazi to obtain that position if, as seemed likely, the Nazis made big gains. Papen called this "a trick", and once more voted against his party ((FVP 110)). Soon afterwards he moved his home to the Saar and ceased to be an M P in the Prussian parliament ((FVP 110)). Meanwhile at national level it had become impossible to form coalition governments in the Reichstag. When the President dismissed Bruning, he asked Papen to form an administration. The choice was most surprising as Papen was not even a member of the Reichstag. He later wrote "I am often asked how it was that someone in my position, in a more or less continuous state of conflict with the other members of my party, and with no record of high public office, acquired sufficient influence to be offered the post of Chancellor" ((FVP 114)). The answer appears to be that the President wanted someone, who was so independent in his thinking that he would be able to bring together people across party lines. Papen was firmly on the conservative side of politics yet had personal contacts with the Centre. Also he was on good terms with the army and held the respect of the President ((FVP 116)). Papen proposed that the Centre should form a coalition with the Nazis and Nationalists as this would provide an administration with a parliamentary majority. Bruning replied on behalf of the Centre that he would never sit at the same table as the Nazis ((FVP 151)). Kaas, the Centre party chairman, begged Papen not to become Chancellor ((FVP 157)). He added that if he went ahead he would incur the hate and enmity of his own party ((FVP 157)). So when Papen, in June 1932, became Chancellor, the Centre MPs unanimously deplored what he had done. Papen tried to keep the friendship of the Centre but had to admit that there was no hope of reconciliation ((FVP 151)). In September 1932 the Centre joined other parties in passing a vote of 'no confidence' in Papen's government ((FVP 209)). Some authors state that the Vatican was pleased when Papen replaced Bruning. There is no evidence for this. The accusation is based on an uncritical acceptance of Communist propaganda. After fresh elections in November of that year, Papen again asked the Centre to join with the Nazis and Nationalists in a coalition. Papen considered that if the President refused the largest party a say in the formation of a government, he would be violating the constitution ((KCA 8140)). But again the Centre refused ((FVP 212)), and condemned Papen's policy. It suggested that as the Nazis were the largest party they should shoulder the responsibility and the unpopularity of forming a government. Even with Papen's Nationalists as allies they would not command a majority, but the Centre would consider 'tolerating' such a coalition (i.e. abstaining on votes of no confidence) so that it could rule within the democratic system. Hitler would not agree as he knew that the Centre would only abstain while moderate policies were being pursued. Any attempt to introduce racial or dictatorial legislation would provoke the Centre into toppling him. Hitler was only willing to be part of a government which ruled by Presidential decrees and so be free from parliamentary restraint. On the 30th of January 1933 the President reluctantly named Hitler as Chancellor in a Nazi-Nationalist administration, with Papen as vice-Chancellor. Presidential decrees would put its laws into effect. It was hoped that Presidential authority and the army would prevent Hitler becoming too powerful. Unfortunately the President aged quickly and became politically inactive, while the army became generally sympathetic to Hitler ((FVP 258)). After the President gave Hitler dictatorial powers on February 28th and the Hitler led coalition parties received a majority in the elections of March 5th, Papen accepted that a 'one party' system of government was the only way out of Germany's problems ((KCA 8140)). It was on the 5th of March 1933 that Papen for the first time became an MP in the Reichstag and it was as a Nationalist, not a Centre Party member. As Papen was not a member of the Nazi party, he was not excommunicated by the Church. During the March election he had warned that pride of race 'must never develop into hatred of other races' and 'there was no need to found a new religion to bolster the German race' ((FVP 268)). In August 1932 a German delegate to the Jewish World Congress in Geneva had praised the Von Papen government's attitude towards the Jews ((FVP 285)). Papen soon became disillusioned with the way things were going. On the 17th June 1934 at Marlburg University, while still vice-Chancellor, he publicly denounced Nazi attacks on free speech, the law, human rights, a free press, personal liberty and the churches. He said that the country had to choose between Christianity or Nazism ((FVP 309)). He condemned the reign of terror and warned the Nazis not to confuse virility with brutality. He declared that the one-party state was acceptable only as a transition stage on the way to an authoritarian but democratic state based on Christian principles ((FVP 307-9)). Although publication of the speech was banned in Germany, copies were spread secretly, and reported abroad ((KCA 8230)). Next day he handed in his cabinet resignation, but Hitler persuaded him to wait until an investigation had been made to discover who had banned his speech being reported. Two weeks later, Hitler had all those likely to lead any attempt to overthrow him, murdered. These included Erich Klausener, the leader of Catholic Action, who had helped to draft Papen's speech ((WLS 218 and 223)), Fritz Gerlich, a Catholic editor, and Adalbert Probst, a well-known national Catholic Youth leader ((KG 61)). One of Papen's private secretaries was killed and two others sent to concentration camps. Papen was arrested but his life spared, probably because of his strong personal friendship with the President. Also, without an organisation, he presented little threat to the regime. Hitler convinced him that there had been a plot to start a civil war, and it was unfortunate that some innocent people had been killed in error. Papen withdrew from the government in July ((FVP 263)). He served as ambassador to Turkey during the war and was found not guilty of war crimes at the Nuremburg trials (KCA 8140, 8227, 8230 and FVP 570)). He was found guilty, of assisting Hitler in preparing for the Austrian Anschluss by a denazification court in 1947. He claimed that the Court was biased as it consisted of four Socialists, one Communist, one Liberal and one Christian Democrat, with the President and his deputy both being Jews. On appeal in January 1949 he was immediately released from prison ((FVP 579)). COMMENT Papen conducted a very independent and personal policy through all these years and did not remotely represent, either officially or unofficially, the political views and policies of the Catholics of Germany.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||