|

The ChurchinHistory Information Centre www.churchinhistory.org

St. Joan of Arc BY

CHAPTER I

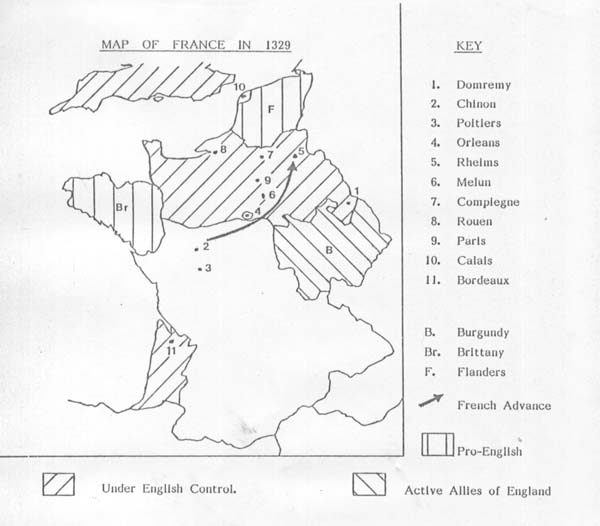

The Church tried her for witchcraft and had her burnt as a Witch. But 500 years later the Church decided that she had been a saint, and officially recognised her sanctity in 1920 by canonisation. For many people, knowledge of Joan's life and the issues involved at her trial, is based on Bernard Shaw's play 'St. Joan'. In this she is portrayed as being the first 'Protestant' because she defied the authority of the Catholic Church. She is also depicted as a feminist fighting against male prejudice. Shaw presents the clergy involved in the trial as sincere, devout Catholics implementing, to the best of their ability, the intolerant doctrines and laws of their Church. Others have gained knowledge of Joan from the pens of authors who have mixed legends with facts, to produce a sentimentalised Joan. She is painted as a heroine in shining armour, as if in a fairy story divorced from reality. Only an examination of the historical facts, will correct the misconceptions gained from a too brief account, the grotesque distortions of Shaw, and the sentimentality of romantics. Criticisms of the Church are centred on Joan's trial, so it is not proposed here to present a detailed record of her whole life. But an outline is required, so as to enable the reader to understand the motives and arguments surrounding the trial. CHAPTER II A THE HUNDRED YEARS WAR In 1340 Edward III of England invaded France to assist a rebellion in the Flanders area of France, and started a war which would continue intermittently for a hundred years. By the early 15th Century the northern and southwestern parts of France were under English control. The French were weakened by internal divisions, with king Charles V suffering from sporadic attacks of insanity ((MGAV 14)). As his sons were still children, the country was ruled by the Queen and a group of Dukes. Rivalry eventually led to civil war in 1418 between the powerful Duke of Burgundy, known as 'John the Fearless', and the other Dukes — who were known as the 'Armagnac Party'. The Queen supported Burgundy, but as her son Charles grew into manhood, he allied himself with the Armagnacs. The Queen was German by birth and had little interest in France, lived an immoral life ((MGAV 21)), and eventually became the mistress of John the Fearless. In 1419 John the Fearless was murdered by a group of Armagnacs in retaliation for a previous murder. The Queen's son, Charles, was close to the scene of the murder, and the son of John the Fearless, who now became Philip Duke of Burgundy, swore that he would never recognise Charles as king of France when Charles VI died. The Queen exercised control over the king during his more lucid moments and found it easy to influence his mind against his son Charles and the Armagnacs. He was persuaded to issue a decree disinheriting his son, because of the murder, and nullifying his right to the throne. At the same time it was repeatedly asserted that Charles, who was also known as 'The Dauphin', was not the king's child but was illegitimate. Queen Isabella did nothing to deny this, and her reputation was such that the assertion was widely believed. (The word 'Dauphin' was the title given to the son who would accede to the throne on the death of a king.) In 1420 the Duke of Burgundy signed a treaty with the English by which the son of Henry IV of England would marry the daughter of Charles VI of France. By this means, a male child of the marriage would be king of both England and France, thereby excluding the Dauphin from the throne. In 1422 both Henry V of England and Charles VI of France died. By then a male child had been born and, named Henry, was proclaimed as king of the two countries. As he was only nine months old, the Duke of Bedford acted as Regent and effective ruler. The Armagnacs recognised the Dauphin as king. They considered that, even if the Dauphin when 15 was involved with the murder of John the Fearless, this would not cancel his right to succeed to the throne, that the old king was of unsound mind and under Burgundian control when he disinherited his son ((MGAV 32)), and that the story of the Dauphin being illegitimate was no more than part of the propaganda war. Kings of France had to be crowned in Rheims Cathedral. As the Cathedral was in English hands this was impossible and this led some sections of the population to give the Dauphin less than full acceptance as king. The fight for the minds and hearts of the people, many of whom were confused as to which side

to support, was as important as the military operations. Some areas believed that they would prosper economically

if linked to England. The English and their Burgundian allies had a strong army, and the town of Orleans was surrounded.

It was generally agreed that if this town fell French morale would collapse further, that many towns would sign

pacts with the English to avoid being attacked, and that the Dauphin's forces would have to retreat to the far

south. France was on the verge of ceasing to exist as a separate country and monarchy. Jeanne D'Arc (D'Arc being her surname) was born in the small village of Domremy in eastern France during 1412. She did not receive an academic education but, as her parents were village leaders, would have been well trained in the domestic arts and farm husbandry. She would have been taught how to pray, to participate at Mass and receive the Sacraments, to live within the moral law, and to develop those human relationships expected of a Christian. Joan first heard 'voices' in 1424, and these continued regularly over a period of four years, during which time she developed as a mystic. The 'voices' then informed Joan that she had been prepared for a special mission to drive the English from France. She had to relieve Orleans, clear an area of northern France of enemy troops so that Rheims could be captured, and then lead the Dauphin to be crowned in its Cathedral. So In January 1428, at the age of 17 or 18, Joan set out on her mission. By July 17th of the following year she stood with her standard in a place of honour beside the Dauphin in Rheims Cathedral, while he was being crowned as Charles VII of France. For an uneducated peasant teenage girl to have made such an impact on European history in the space of a few months is unique, and considered by many to be Joan's greatest 'miracle'. Although Joan said, "Now the will of God is done" ((SS 165)), she stayed with the army and urged an immediate advance on Paris. But the king decided to consolidate his military position by capturing the Burgundian towns to the south of Rheims. Later, as Joan stood on the ramparts of Melun to the south of Paris, her 'voices' said that she would be captured by May of the following year. This prophesy came to pass just outside the town of Compiegne. While the French forces viewed Joan as 'The Maid of God' (Pucelle de Dieu) and as a sign of God's blessing on their cause, the English and Burgundians, not disputing her supernatural powers, saw her as a Witch working for the Devil. The Duke of Bedford knew that if he could show that Joan was not a holy person but a witch and heretic using occult powers, it would indicate that Charles VII had been crowned king through the power of the Devil, not that of God. This would greatly affect public opinion, undermine the morale of the French army and revive that of the English and Burgundians. The only authority able to judge Joan on such a religious issue was a church court. So it was decided to establish one to find her guilty of witchcraft. Being careful, the English made it clear that if Joan was found not guilty, she was not to be released but returned to them ((VSW 254)). C BISHOP CAUCHON There were several bishops favouring the English-Burgundian cause, but their first loyalty was to Christ and justice, and therefore they would not be willing to hold a political trial under the cloak of a religious one. A church court had already tried Joan at Poitiers in the spring of 1429, and had found her: 'A good person and nothing to suggest she is a mischief maker'. ((AR 9)). But there was one bishop, Cauchon of Beauvais, who was completely devoted to the English-Burgundian side. He had fraternised with Caboche, the scourge of Paris ((SS 196)) and had gathered supplies for the English army ((SS 61)). He was assisting them whenever possible and led the negotiations to have Joan transferred from Burgundian to English hands. To raise the vast sum paid by the English for her ((SS 198)), a special tax was levied throughout Normandy ((VSW 242)). Cauchon was the obvious man to carry out the plans of the English, and he was willing. CHAPTER III a. PRELIMINARIES Cauchon faced a legal problem when he commenced his work. According to Church law a bishop could establish a Court only within his own diocese, and Beauvais had now fallen into French hands making Cauchon a refugee. The English solved this problem by moving Joan to Rouen, which was temporarily without a bishop. It was also the headquarters of the English army with a large military garrison. Cauchon was then able, with the assistance of the strong army presence, to exert pressure on the Cathedral Chapter to allow him to establish a Court there ((SS 202)). Many legal authorities consider that this was illegal under Canon Law ((WSS 230)). Cauchon claimed the right to judge Joan because she was captured in his diocese. But we now know that Joan was not captured in his diocese, but a few metres away from the bridge over the river outside Compiegne, which defined the diocesan boundary ((WSS 230)). Before a Court could be established, information had to be gathered to show there was sufficient evidence to justify holding a trial. Cauchon sent emissaries to scour the country for compromising facts concerning Joan. But however diligently they searched, It was impossible to produce witnesses willing to testify to any shameful or compromising occurrences in which Joan had been involve ((SS 205)). Nicholas Bailly had, investigated Domremy and the surrounding five or six villages and found nothing: "he would not have wished to find in his own sister". Cauchon was furious with him, as if he were a traitor, and refused to pay him for his work ((SS 205)). There was no sign that Joan had ever taken part in occult practices. Cauchon tried to prove that Joan was not chaste and asked the Duchess of Bedford to examine her. She reported that Joan was a virgin ((SS 205)). Despite these failures, Cauchon called together a number of people and informed them that the preliminary evidence justified a trial. When one of the priests asked Cauchon to produce the preparatory reports, Cauchon promised to do so ((SS 205)). But he then wrote them himself, and based them on rumour and scandal ((SS 206)). It was in this manner that Cauchon obtained the agreement of other priests and theologians to establish the Court ((SS 205)). b. THE COMPOSITION OF THE COURT If the verdict of the Court was to be accepted widely it was essential that the officers and Assessors (a form of jury) should be drawn from a broad range of places and institutions. So Cauchon appointed his Assessors from a wide range of institutions while ensuring that the individuals chosen were committed to the English-Burgundian cause and therefore biased emotionally against Joan. If Joan's powers came from God, then they were supporting a war against God. This did not mean that all were so attached to their political faction that they would not try to be fair, and be open to Joan's arguments. Cauchon assembled a Court which, apart from his small unscrupulous and well organised followers, was composed of learned but biased and timid individuals. c. THE CONDUCT OF THE TRIAL It was certainly not a fair trial ((VSW 254 and WSS 103)). Bishop Cauchon arranged the trial and issued the orders, but the whole weight of the English army was behind him, and any who showed independence of thought knew that Cauchon had the power of life and death over them. The Duke of Warwick, who commanded the English army, and his assistants, had access to every stage of the legal process. They were able to put daily pressure on all who took part. In the narrow passageways of the town, swarming with soldiers and political agents, a man of independent thought could easily have an 'accident'. Those concerned with the trial were a mixed lot. 'Among them were men of intelligence, probity, compassion, men who disapproved of the way the proceedings were conducted, men who would gladly have given justice and humanity a better chance. But there were few among them who openly dared even to hint at such opinions. The wrath of the bishop of Beauvais was not a thing lightly to be incurred, and there is no doubt that he held them subdued and afraid' ((VSW 253)). 'There was no room in the same Court for Cauchon and for liberty of speech. The slightest dissentient murmur was instantly suppressed. It was quite clear who meant to be master in that Court, and they all knew it. And behind the menacing figure of the Bishop was the whole power of England. Rouen, to all intents and purposes, was an English town, and everybody in Rouen knew very well that the English had no intention of letting their prisoner go. ... whenever they thought they detected any signs of weakness or hesitation on the part of the religious tribunal, protests were registered, not always without hot words. Stafford's sword was ever ready to leave the scabbard' ((VSW 254)). Joan: 'was granted no advocate at the trial: no single witness was called on her behalf: no single member of the party favourable to her was among her judges: no one dared to raise his voice to assist or direct her: ... ' ((VSW 255)). d. SOME INCIDENTS DURING THE TRIAL i) Nicholas de Houppeville attended the preparatory meetings, and had the courage to tell Cauchon that neither he nor anyone else present could legally act as judge in this case; that the bishop of Beauvais could not judge a woman whose case had already been decided by his superior, the Archbishop of Rheims (at Pottier), and that it was quite apparent that this was a case of political opponents masquerading as judges in a question purely of faith. Cauchon was furious and later disqualified him from being an Assessor, making him leave the Courtroom. As a priest of the diocese of Rouen, Houppeville was not under Cauchon's authority and would not give way. A few days later he was arrested and thrown into prison. Cauchon's men were just about to surrender him to the English when his friend, the Abbot of Fecamp, managed to save him. No more was heard of him during the trial ((SS 224 and WSS 105)). ii) Jean de Saint-Avit, bishop of Avranches, was called to assist at the opening of the trial, but reported that he was not satisfied as to the competence of Cauchon to act as judge. He suggested that the Pope or a Church Council should be asked to judge the case. Cauchon promptly removed his name from the list of Assessors. He was probably saved from prison due to his office of bishop ((WSS 104)). iii) Andre Marguerie asked some unwelcome questions and was told to hold his tongue ((VSW 254)). iv) Bishop Jean Lefevre intervened to say that a question being asked of Joan was a big one of deep theology and Joan being a peasant had no need to answer it. He was told to be silent: 'Taceatis in nomine diaboli' (Be quiet in the Devil's name) ((VSW 254)). v) Jean de Chatillon was told to keep quiet and let the judges speak, or he would only be allowed to attend the sittings when he was sent for ((VSW 254)). vi) Jean Craverent, the General of the Inquisition of France, disappeared. It is suggested by modern Dominicans that he understood the purely political import of the trial and preferred not to be involved in it ((SS 208)). vii) Jean Lemaistre, deputy Inquisitor, was pressed by Cauchon to take part. But he claimed that he lacked the authority to act as a judge ((SS 208)). He then said that he would not act without instructions from Graverent. But later he informed a friend that if he didn't take part it would cost him his life ((SS 212)). viii) Jean Tiphaine, a, doctor who treated Joan in prison, admitted afterwards that he had only attended the trial through fear ((VSW 278)). ix) Ysambard de la Pierre attempted to give Joan some advice, and was told to be silent in the Devil's name ((VSW 254)). Later that day he went, accompanied by two other monks, (Jean De la Fontaine and Jean Duval) to visit Joan in her cell. They told her that she must not believe that this tribunal represented the Church Militant (i.e. the visible Catholic Church on earth). She should appeal to a General Council and only accept the authority of the Pope. Warwick caught them, and in a rage threw himself on Ysambard. He threatened that if he repeated his advice to Joan he would be thrown into the Seine ((SS 250)). De la Fontaine and Duval fled in terror back to their monastery ((SS 250)). x) Jean De la Fontaine was one of the two Prosecutors, so played a vital part in the trial. While making preparatory enquiries regarding it, he realised that evidence favourable to Joan was being suppressed. Towards the end of the trial he visited Joan in prison. After being caught by Warwick with Ysambard (see ix above) he ceased to attend Court after the 28th of March and left Rouen in haste ((VSW 253)). xi) Jean Lohier, an ecclesiastical jurist, paid a visit to Rouen and, being a friend of Cauchon, was permitted to see the papers of the trial. When he returned them to Cauchon he was categorical: The trial was invalid, if only because of the numbers of errors in procedure; a trial must take place in conditions which permit all to give their real opinion freely; Joan is only an ignorant girl who cannot possibly answer satisfactorily all those learned questions. He was filled with disgust and left for Rome ((SS 223)). xii) Guillaume Manchon was the chief clerk of the Court. The trial was being conducted in French, but when Cauchon dictated Joan's replies to Manchon he used Latin. Repeatedly Cauchon tried to misreport her words, but Manchon very bravely refused to write until he had obtained Joan's replies correctly. This happened on five days running ((SS 211 and 216)). xiii) Pierre Bosquier, a Dominican monk, expressed his opinion of the trial to some friends on the day following Joan's execution. His criticisms were heard by one of Cauchon's agents and he was accused of supporting heresy. He was panic stricken and apologised humbly, claiming he was drunk at the time. He was thrown into prison to live on bread and water for nearly a year ((WSS 105)). e. CAUCHON'S CLOSEST SUPPORTERS These were a despicable group of individuals who, under Cauchon's guidance, dominated the conduct of the trial. i.) Jean d'Estivet was the main prosecutor and, after Jean De la Fontaine had fled, the only one. He was sarcastically nicknamed 'Benedicite' because of the appalling insults, blasphemies and curses continually pouring out of him. He called Joan a whore and worse to her face, and on one occasion Warwick, who was fairly tough, had him thrown out of the cell because he was acting brutally towards her ((SS 207 and VSW 253)). ii) Nicholas Loiselleur visited Joan in prison prior to the commencement of the trial, and pretended to be from near Joan's home village and to be pro-French. He so deceived her that she asked him to hear her confession and give her advice. He had arranged for two Notaries to sit outside the door and take notes. d'Estivat also took part in these tricks to try and find evidence against her ((VSW 250)). iii) Guillaume Erard (or Evrard) was a violent and energetic man who was being paid by the English for every day he was in Court ((VSW 253)), although in this he was not alone. iv) Gilles de Duremort was another of whom it was said that he seemed inspired by a hatred of Joan and a love of the English, rather than by any zeal in the cause of justice ((VSW 253)). v) Thomas de Courcelles, Aubert Morel and Nicholas Loiselleur wanted to torture Joan ((VSW 284)).

In accordance with normal practice, it was necessary to send a precis of the case to other church authorities for their opinion. This was to ensure that any bias of a Court would become apparent. But the main authority to which the precis was sent was the University of Paris. Its members were strongly pro-English and Burgundian, the pro-French theologians and jurists having fled to the south of France. The seventy charges against Joan, together with her replies, were summarized by Cauchon into 12 articles. ' ... it was a cleverly woven tissue of truth and lies, so inextricably mingled that it would be impossible to deny any statement in toto; ... ' ((WSS 104)). Three of Joan's most determined enemies - Jean Beaupere, de Touraine and Nicholas Midi - accompanied the précis to Paris so as to explain it to the theologians ((VSW 279 and 284)). It is not at all surprising that the University of Paris, on this evidence, found Joan 'guilty'. g. THE CONDEMNATION OF JOAN When the delegation returned from Paris and announced the judgement of its University, the Rouen Assessors were not aware of the 'evidence' upon which Paris had based its view. If any brave voice at Rouen now tried to defend Joan, it was not only the force of Cauchon that had to be overcome, but the prestige of the combined Faculties of Theology and Law at Paris University. Joan's position was hopeless, and no one dared to dissent when the final vote was taken. She was condemned as guilty of heresy, blasphemy, idolatry, conjuring up evil spirits, schism, desiring to see human blood shed, uttering false revelations derived from the evil and diabolical spirits, Belial, Satan and Behemoth ((SS 267)). Joan was overcome by fear when she stood awaiting execution and signed a short document "I confess that I have most grievously sinned, in falsely pretending to have had revelations and apparitions sent from God, that is angels and Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret; et cetera." ((WSS 115)). The original of this document has become available only in modern times. The so-called 'Authentic Document' later published by Cauchon, greatly extended the 'et cetera' to include an admission of witchcraft, blaspheming God and His saints, wearing dissolute dress, behaving contrary to Divine Law, the Holy Scriptures and canon law ((WSS 115-6)). Although the true short document was not available at the 'retrial' of 1455, the Promotor at that trial was convinced that the longer version published by Cauchon was an invention ((WSS 116)). All witnesses said that Joan signed a very short document. h. RETURN TO JAIL As Joan had recanted, she was taken back to her cell. The English commanders and their troops were angry that at the last moment Joan had escaped death ((WSS 116)). The announcement of her recantation would not have the same propaganda impact as would a report that she had been burnt as a Witch. During the next three days Joan was brutally treated by her gaolers, which implies that their previous orders had been changed. An attempt to rape her was made by an English Lord. One morning she found that her dress had been removed and replaced by male attire, so she had to wear it in order to visit the toilet. Cauchon came quickly to her cell to find this wearing of male clothes 'proof' of her disobedience to 'The Catholic Church' (ie himself). He pronounced Joan a 'relapsed heretic' and on leaving the prison rejoiced with the English soldiers with the words "She is caught" ((WSS 119)). Joan now realised that she was going to be executed after all. She said that her recantation had been due to fear and the belief in the promise that she would be handed over to the Church authorities away from Cauchon and the castle. She restated all the claims and answers that she had made during the previous weeks. i. EXECUTION Heresy was viewed as an offence against the civil government so, although the Church was required to examine the accused and decide whether the accusation was true, it was the civil authorities that passed the laws, sentenced and carried out the penalty. On the day of her execution she held up the proceedings by over half an hour of prayer and conversation with priests who were trying to comfort her ((SS 284)). Cauchon did not interfere as these priests could do nothing to save Joan's life. Many, including members of the clergy, were crying. When the 800 fully armed English troops grew impatient, two of their officers seized hold of Joan and took her to the stand of the town Councillors. The Councillors remained silent, not wishing to be involved in a judicial murder. 'No lay sentence was pronounced; that seems certain. None is officially recorded, and all the witnesses agree that none was delivered' ((VSW 299)). The deputy Bailli of Rouen simply made a gesture with his hand, saying: "Away with her". ((WS 123 and VSW 299)). j. REHABILITATION AND CANONISATION Under the authority of the Pope, an inquiry regarding the 1431 trial was established in 1455. The term 'Retrial' is frequently used, but it was not a 'retrial' of Joan, her sanctity, the validity of her alleged miracles, nor the origin of her 'voices'. It was not a trial of Cauchon who, together with most of his associates, had died in the quarter of a century since Joan's death. The new inquiry was limited to judging whether the trial of 1431 had been legal and just according to the teachings and laws of the Catholic Church. After hearing 80 witnesses in detail, and examining great quantities of written material, the verdict was announced on 7th July 1456. It stated that the original judgement had been based on 12 forged Articles of accusation ((SS 289)). The previous sentence was 'full of fraud and deceit, totally contrary to both law and equity', and that it was 'broken and annulled'. ((WSS 129)). Although not part of the verdict, the evidence clearly pointed to Joan's virtuous life, sincerity regarding her claims, and to her loyalty to Christ, the Church and the Pope. Respect for Joan's heroism persisted for over 450 years until popular demand led the Church to investigate her sanctity. In 1920 Joan was canonised (ie recognised by the Church to be in heaven). To make this pronouncement the Church normally requires evidence of three miracles worked by the person who has died. Miracles alleged in the past were considered to be too far lost in history, and combined with legends, to be considered reliable. Modern miracles, worked through her intercession, were accepted as meeting this requirement. CHAPTER IV A. BISHOP CAUCHON'S MOTIVES Cauchon sat on the English Royal Council and received a salary for doing so ((VSW 241)), and showed more interest in politics and in the conduct of the war than in religious and spiritual affairs. But his motivation in supporting the English-Burgundian side could have been a sincere belief in the righteousness of their aims rather than mere self-seeking. He was ambitious, but this in itself is not a moral fault. The importance of Joan's impact on the war, due to her success in raising the confidence of the French troops and undermining that of their opponents, was widely recognised. At the time of her capture Cauchon, in common with the universal view of his side, held that Joan was either a fake, a self-deluded girl being manipulated by politicians, or an agent of the Devil. When Cauchon undertook Joan's trial he was confident of being able to expose her sacrilegious claims. Frustrated by the lack of evidence against Joan, he would not find it difficult to convince himself that this was due to a clever hiding of data. On this premise he might justify, in his own mind, subverting Church laws in order to 'expose' her. As the trial proceeded he was drawn into greater and greater acts of illegality and would have found it very difficult to face facts and extricate himself from his situation. To have acknowledged Joan's innocence would have dealt a massive blow to his public Image, and imply that he and his colleagues were helping the wrong side in the war. The English commanders would have judged him a most dangerous man and ensured that he had an ‘accidental’ death very quickly. Cauchon did not possess the virtues of humility and courage, but this does not mean that he was devoid of all decent feelings. There is no evidence that Cauchon held any personal animosity towards Joan, or wanted to inflict cruelty for cruelty's sake. He may have come to see a repudiation by Joan of her 'voices' as not only being necessary for the English-Burgundian cause, and a means of saving his own reputation and neck, but also as a way of saving Joan's life. He would not have expected Joan to be so tenacious. When Joan recanted due to fear and was returned to prison, the generally held opinion of the English was that Cauchon was pleased. But the English soldiers were enraged, and pursued and threatened the judges. Warwick was furious and openly blamed Cauchon for permitting Joan to escape with her life. It is possible to accept this view of Cauchon. He may have considered that the effect of Joan admitting that she was a liar, and had been involved in the occult, would have been sufficient to turn the tide of public opinion and the fortunes of war. He could then have imprisoned her for a time and avoid being responsible for her judicial murder. On the other hand it is possible to believe that Cauchon always intended Joan to die, but her public recantation left him with no alternative but to return her to prison, and await an opportunity to procure her: 'relapse into heresy'. Whichever view is correct as regards Cauchon's motives and objectives, he was certainly guilty of using his position in the Church for a purpose unconnected with the aims of the Church. Cauchon was later appointed bishop of Lisieux in 1432 ((MGAV 65)), but was then accused of stealing funds destined for Rome. The Pope excommunicated him, but he defiantly continued to offer Mass. Only when the Pope threatened to make his excommunication public and depose him, did he agree to pay back the money ((SS 197)). He died in 1442. B. THE WEARING OF MALE DRESS IN FRANCE Cauchon placed great emphasis during the trial on the 'scandal' of Joan dressing as a man. Modern readers may see this as a sign of Church narrow-mindedness at that time. But it is dangerous to jump to this conclusion. The manner in which a person dresses frequently indicates a life-style and a philosophy of living. In modern life a lawyer will often advise a client to avoid unconventional hair- styles and clothing when appearing before a jury. In Joan's day, girls who dressed as men were often giving a sign that they were loose living or opposed to the normally accepted standards of public behaviour. So Cauchon knew that if she appeared in Court dressed as a man, some of the Assessors would become biased against her. As Cauchon was without any real evidence against Joan, he found it important to stimulate hostile emotions. When the English army handed Joan over to Cauchon for a 'Church' trial, he kept her In a castle cell guarded by men, which was against the law of the Church. Joan should have been placed in a church prison, where she would have been guarded by female warders and been able to dress as a woman without fear. She could have washed and groomed herself so as to present a decorous appearance before the Court. Cauchon made the question of her dress a central part of the trial, while keeping her surrounded by men, so that she had to continue to wear it to protect her virginity. Cauchon ordered her in the name of: 'The Church' to change to female dress, but his strictures in no way represented the views of the Catholic Church. (The circumstances in which she dressed as a man again, were related on page 13 of this publication). When Joan was condemned for the second time because she had again dressed as a man, she burst into tears and said, "Oh, if only I had been in the hands of the Church instead of in those of my enemy I would never have come to this terrible end!". She says to Cauchon, "My Lord Bishop, it is you who murder me". She accepts that she broke her promise not to wear male attire again, but repeats that if she had only been placed in an ecclesiastic prison this would never have happened ((SS 281)). Cauchon quoted Deuteronomy XXII verse 5 out of context. The rest of the book shows that it was part of a long list of rules appertaining to a particular time in Israel's history. It is a great mistake to judge the whole Church and people of France by Cauchon's attitude in his Courtroom at Rouen. The Commander and his assistants who sent Joan to the Dauphin raised no objection to her dress, she was allowed into the Dauphin's Royal Court without changing, and spoke to the Dauphin in private. Her trial before an archbishop at Poitiers in March-April 1429 did not lead to a condemnation of her manner of dressing. The Archbishop of Embrun, Jacques Gelu, who at first had been shocked at Joan's attire, also delivered a carefully considered judgement that it was necessary for the work that she was doing ((HT 405)). She wore it for three years while playing a prominent part In French history. The people of Orleans and other towns cheered her, and she lived in daily contact with the leading churchmen and aristocracy without criticism. It was her habit to attend Mass every day, so during her travels around France she would have visited many churches. Yet there is no evidence of any priest refusing her entry or Communion because of her form of dress. When the Dauphin was crowned king in Rheims Cathedral in 1429, Joan was by the high altar in a place of honour, dressed as a man. French society, from the lowest peasant to the highest dignitary of Church and State, recognised her dress as necessary for conducting warfare and as a protection of her chastity, not as a sign that she wished to attract attention as a rebel against Christian morality. C.THE MORNING OF JOAN'S EXECUTION Events connected with Joan's last hours have presented historians with problems that are unlikely to be fully resolved. i) During her imprisonment, Joan's requests to receive Communion, or at least be allowed to pray at the door of the chapel, were repeatedly and firmly rejected by Cauchon. She was a suspected Witch, was the reason he gave. Yet now that she had been convicted of that crime, he permitted her to receive Communion. This was not done secretly, but the Sacrament was brought in procession to her cell accompanied by lighted candles and the tinkling of a small bell. ii) A week later the judges and seven Assessors met and, on the 7th of June, a document professing to contain the sworn deposition of the Assessors, recording what they heard Joan admit during her last hours, was added to the official report of the trial. One of the Assessors also added that Joan had promised to disavow her 'voices' on the scaffold. The next day this Supplement was despatched in the name of the king of England to royal personages and bishops all over Europe. A week later it was sent to the university of Paris, the Pope and Cardinals in Rome. iii) Witnesses had authenticated every page of the minutes of the trial but this page. It was the most important of all as it contained the words Cauchon had spent months trying to get Joan to utter and had been despatched all over Europe. It was not signed. At the 'retrial', Manchon declared that Cauchon had asked him after Joan's death to attest to evidence that he had not himself heard given, and he had refused. Both Fr Ladvenu and Manchon were very close to Joan during her last minutes and both deny that she disavowed her 'voices'. According to the Supplement it was Fr Ladvenu who gave Joan Communion, after she had denied her 'voices' in front of him. Yet at the 'retrial' of 1455 he gave evidence in favour of Joan. The retrial Court treated the Supplement as a forgery. So there is no reputable evidence that Joan denied her 'voices', and her constancy in death confirms this. And according to Cauchon's public judgement she remained a Witch in rebellion against the Church. iv) Anyone who is aware of Catholic belief is astounded that an

unrepentant One possibility is that it was part of the scheme to give credence to the story that Joan had repented on that last morning, and had therefore been able to receive Communion. But there is no record of her receiving the Sacrament of Absolution (Forgiveness) which in this case would have been necessary. Another possibility is that Cauchon had become convinced of Joan's innocence, but considered her death to be politically and personally expedient. It is conceivable that his guilty conscience made him willing to make her last v) Whatever motive Cauchon had, it is quite clear that it was completely divorced from that of the Church's teaching. D. THE DAUPHIN (KING CHARLES VII) The title of: 'Dauphin' was held by the heir presumptive to the throne. When Charles VI died in 1422 the Dauphin was recognised by his supporters as king, but historians often continue to refer to him as: 'The Dauphin' until he was crowned in 1429. There is a danger that Joan's impact on events has become exaggerated and romanticised. Anecdotes concerning her life are uncritically taken as facts, and the achievements of those associated with her tend to be eclipsed. In English history the Dauphin, who was already king when Joan first met him, is often presented as a timid, feeble minded, sickly and irresolute young man, overawed and laughed at by his advisors, and having his kingdom regained for him by a young girl. It is said that he was ungrateful to Joan and did nothing to save her. It is also sometimes asserted that he reluctantly agreed to the 'retrial' due to the pressure of Joan's relatives. But this picture of Charles needs to be questioned. He was 18 when he became leader of half of France due to the insanity of his father, the treachery of his mother and the rebellion of Burgundy, the largest Duchy. It would have been foolish for him to have ignored his more experienced advisors at that time. But records show that he took an intelligent part in important state meetings during his teenage years ((MGAV 27)). Being deeply religious and well educated ((MGAV 42)) he attended Mass daily and never allowed state business to interfere with his prayers ((MGAV 43)). His chaplains did have to warn him against listening to astrologers ((MGAV 44)), but this was common in those days. He had a dislike of bloodshed ((MGAV 35)) and accepted the need to fight for his crown and country reluctantly. He preferred to use diplomacy and bribery in winning cities and influential landowners to his side. This attitude exasperated his more aggressive military commanders and led to his reputation of not being willing to fight. But at times he could be very resolute ((MGAV 42)) and could be stung into fury and act cruelly ((MGAV 42)). Charles was not so naive as to place Joan in command of his army after a short meeting with her. He waited for the Church Tribunal at Poitiers to give its verdict before he put her in command of the small group of men who had volunteered to fight under her. The continual claims of the Burgundians, supported by his mother, that he was illegitimate and therefore had no right to the throne, could have had an inhibiting effect on a sincere young man of religious principles. If this accusation was true he was fighting for an unjust cause and must bear the guilt of tearing France apart in bloodshed and destruction. Joan was prominent during two years only of his 39 year reign, and had very few soldiers under her personal command. It may be said that Charles would not have rallied the French without Joan, but it was Charles who conducted the war and its aftermath. When he became king in 1422, France was in a desperate situation, but at his death the English were left with only the town of Calais. Burgundy had submitted, and by patient diplomacy he had healed much of the bitterness of the civil war to leave a united and well administered country. It is not at all surprising that the French often refer to him as 'Charles the Victorious' ((WSS 126)). There was no hope of a raiding party breaking into the castle at Rouen ((SS 199)), and the French did not hold any prisoner of the stature that would have been accepted by England in an exchange. It is difficult to see what Charles could have done to save Joan. Some years passed before a 'retrial' was arranged, but this was because the papers of the trial were at Rouen, which remained in English hands till November 1449. Within four months of its capture Charles opened an official enquiry. He was without authority to order a full Inquiry as this vas a matter for the Church. At this time, Charles' first priority was to reconcile his supporters who had suffered much under English rule with those who had collaborated with the enemy. His supporters wanted their lands to be returned, while Charles wished to extend an amnesty to his former enemies. Reconciling these two pressures called for great tact. 'The re-establishment of social peace ... would not be assisted by the prosecution of old grievances' ((MGAV 68-69)). So it was the relatives of Joan who requested the Church for the establishment of an Inquiry. CHAPTER V a. WHY DID GOD INTERVENE? There have been instances in history when a Catholic might judge a battle or war to have been clearly one between good and evil. In these cases an unexpected victory could be seen as the intervention of God to protect his people. But the situation in France at the time does not lend itself to any such judgement. Both France and England were Catholic countries and although the Burgundian leadership was corrupt, there had been worse. It is difficult to find another instance where God intervened so directly and unmistakably in a war, yet compared to other events in the history of Christianity, the war and issues were of minor importance. It is possible that the unimportance of the political issues should make us see Joan's political role as nothing more than a stage upon which her real work was played. Every generation needs dynamic figures to bring to life within their personalities the teachings of Christ's Church. Such lives show that with God's help it is possible to overcome the apathy, hopelessness, lack of vision and selfishness that prevents many, who give mental assent to Christian beliefs, bringing the Word of God alive in their hearts. Where better could God have placed His saint in order to make this impact? Joan was in the centre of public life and attention, living amid the greatest concentration of youth in the country. Joan insisted that this army, which was to fight with God's assistance, had to purify itself from the sins and scandals which filled the camps with immoralities. Prostitutes were driven away, foul language was brought under control and a sense of honesty expected. Under Joan's influence, corruption and dissipation were replaced by moral integrity and idealism. Great military feats could be achieved with such a force. Due to her influence, how many young men became priests or joined a monastery? How many others saw the dignity of womanhood in Joan, thereby changing their attitude towards their girl friends and future wives? What spiritual impact did she have on the older clerics? Did they become more Christ-centred because of her life and death? We have no way of measuring these spiritual fruits of Joan's life so they are not recorded in the history books, yet they may have been the whole, or at least the main, reason for Joan's mission. b. JOAN'S 'MIRACLES' Joan did not perform 'miracles' such as instantaneously healing a physical disability, nor did she use 'faith-healing'. The remarkable events of Joan's life were connected with foreknowledge and insight.

It is possible to explain some of these events as luck or coincidence. But when all are considered together and in the light of her unique personality, holiness and strict adherence to the moral law, it is not surprising that many accepted her claim to have been assisted by 'visions' and 'voices'. None of her 'miracles' involved the suspension of the laws of nature (e.g: God would know the wind direction would change suddenly, so could instruct Joan when to prepare the boats so as to be ready for the change of wind). Sceptics may assert that Joan's 'voices' were in her imagination. Cauchon put this view to Joan and she replied that God was using her imagination to communicate with her. Joan was a mystic, and like all mystics found great difficulty in explaining her experiences to others. Some mystics have attempted to explain how God acts on their intellect, and this subject is discussed deeply in a long chapter entitled 'Extraordinary Favours, Locutions and Visions' in: 'I am a Daughter of the Church' ((PME Chapter II)). When it is considered how wise were Joan's answers to Cauchon's questioning it is hard to avoid the conclusion that God had infused, by means of mystical contemplation, a deep and profound knowledge of Catholic theology. The Poitiers Tribunal of April 1429 gave a decision in accord with sound, cautious, Catholic principles. It was presided over by an Archbishop, and was therefore a superior Court to that later established by Cauchon. It stated that there was a: 'favourable presumption' to be made for the divine nature of her mission; and: 'to doubt or abandon her, without suspicion of evil, would be to repudiate the Holy Spirit and to become unworthy of God's aid' ((MGAV 56)). This same Archbishop later considered that Joan was falling into an attitude of pride, but this was a separate matter to the authenticity of her 'voices'. CHAPTER VI (i) HIS EARLY LIFE Born in 1856, Shaw lived in Dublin until 20 years of age, when he Although his mother's passion for singing brought her into contact with Catholics and membership of a Catholic choir, she was not religious. Shaw would have received some Protestant education at school and his nurse encouraged him to say prayers, but he does not appear to have experienced a meaningful contact with the positive aspects of Irish Protestantism, such as belief in Christ, love of the Scriptures, worship and prayer. He would no doubt have come into contact with that vocal and negative Protestantism, which was very active at the time, that inculcates a hatred of all things Catholic. The word: 'Protestant' signified in Shaw's family that they were part of a superior social caste, as compared with what was viewed as the uneducated, inferior, native Catholic Irish around them. His father's heavy drinking and his mother mixing with 'low class' Catholics, were the most likely reasons for the middle class branches of the parents' families disowning them. Shaw's transfer to a Catholic school for six months at the age of 13 was a traumatic shock for him, as it symbolised the final abandonment of his 'gentlemanly' Protestant heritage. Shaw kept this social stigma a secret, even from his wife, until he was 90 years of age ((CW16)). (ii) UNDERSTANDING THE PLAY Shaw was a brilliant dramatist. His 'St Joan' was hailed as a masterpiece of international renown ((AG 11)) and as his greatest work. It is used widely in schools as a medium for the teaching of literature and drama. It is not an exaggeration to say that the image which dominates the imagination of the English speaking peoples regarding Joan of Arc, and the Catholic Church in the France of her day, is that gained by studying, reading, acting or viewing this play. But historians agree that it is not reliable as history ((VSW 21)). Shaw was fascinated by the way good forces seemed to be unavoidably in conflict with one another. In 'St Joan' he urged the need for independent minded individuals, like Joan, to defy all institutions so as to keep alive human dignity and freedom. Yet he used the character of Cauchon to show how good men could fight for law and order and uniformity of belief, so as to prevent the growth of nationalisms, heresies and anarchic ideas, which lead to wars and the degradation of civilised living. Some writers have accused Shaw of deliberately distorting the history of St Joan's life so as to discredit the Catholic Church and religion. But most see him as a dramatic artist, not as an historian. They see him as no more interested in history than Moses was in Geology when writing Genesis. Shaw's claim was that he knew history intuitively! He writes his plays, reads the history books afterwards, and finds — so he says — that he was right all along, for: 'given Caesar and a certain set of circumstances I know what would happen' 'He retains his right to be absurd in everything but psychology' ((EB 159)). 'One must however be very clear about the fact that Shaw never tried to do the job of the professional historian. As his way is, he informs everyone that his plays are utterly historical and defends their most whimsical anachronisms in notes that are not uniformly funny' ((EB 159)). 'Shaw differs from a sound historian not in being more subjective but in not being an historian at all' ((EB 160)). 'In Shaw's history plays the controversies over the facts in St Joan are irrelevant'. ((EB 170)). It was in 1913 that he first expressed the wish to write this particular play ((AC 10)), so we may presume it was taking shape in his mind for nine years before he was shown an account of the trial ((AC 10)). This was in early 1923 and he commenced writing soon afterwards ((AC 10)). The play was finished, cast, rehearsed, and had its first performance on December 28th of the same year ((WSS 179)). So little time would have been available to study in depth the results of over 500 years of French historical research on this subject, even if Shaw had wished to do so. We know that aside from Quicherat, It seems that all Shaw read about Joan were the plays and biographies which had helped to create her Legend - Shakespeare, Voltaire, Schiller, Mark Twain etc. ((EB 170 and AG 14)). Shaw said that he would have preferred to have used the life of Mohamet rather than that of Joan for his play, but feared assassination from some Arab fanatic ((CW 269)). He saw the play as: 'The perfect opportunity to express some of his most deeply held views on politics, religion, sainthood and human evolution' ((AG 10)). Conscious of the enormous ignorance of, and blind prejudice against, Catholicism at the time the play was first produced, at least one Catholic viewer felt that, as the play was more temperate in its portrayal of Mediaeval Catholicism than a British audience was accustomed to, it may have had at that time the effect of lessening prejudice ((HT 396)). It is unfortunate that those who read Shaw's play are mainly in their teens and have little idea of the actual story of Joan, the situation in France that time, or the teaching of the Catholic Church. They are therefore unable to protect themselves from absorbing prejudices from this powerful, but historically false drama. CHURCH IN HISTORY does not wish to pass judgement on Shaw's motives and religious opinions. Nor to minimise his ability to provoke viewers into looking at the psychology of human beings, which changes little in the course of ages. It will limit itself to indicating the main discrepancies between the 'history' people are likely to learn from his play, and the correct history of those times. iii) CAUCHON AS REPRESENTING THE CHURCH 'Representation of Cauchon as a man of good faith, such as has been made by a number of writers, notably Bernard Shaw, is quite at variance with the facts' ((WSS 230)). In the play the character of Bishop Cauchon is used to speak for: 'The Church', and to make it appear that his tyrannical, cynical, myopic arguments and twisted cross-examinations were typical of Church thinking and Church Court practice. In Scene 6 he says: "I am determined that the woman shall have a fair hearing. The justice of the Church is not a mockery". So Cauchon is presented as a good sincere Catholic bishop, mentally crippled by a narrow-minded religious belief which leads him logically to attempt to crush Joan's open and free spirit. But in reality Cauchon was an ambitious man, defying Church teachings and laws, and knowingly misusing his position within the Church to pervert justice. There is nothing in Shaw's play to inform the viewer that the Catholic hierarchy throughout France at the time was organising prayers for Joan's safety, vindication and freedom ((ACTS 21)). (iv) THE TWO TRIALS Through his characters Shaw repeatedly asserts that the first trial under Cauchon was sincerely conducted and in accord with Catholic teaching and laws, while the second was a political charade. This is summed up in the last scene where the ghosts of Joan and other characters return to discuss with Charles what had happened. Charles tells Joan that; "The Courts have declared that your judges were full of corruption and cozenages, fraud and malice". To which Joan answers; "Not they. They were as honest a lot of poor fools as ever burned their betters". Speaking about her exoneration at the second trial, Charles says: "I shall not fuss about how the trick was done". Cauchon exclaims: "Yet as God is my witness I was just; I was merciful; I was faithful to my light; I could do no other than I did". Later he adds: "The Church Militant sent this woman to the fire". Lavenu explains how: "The ways of God are very strange. The first, legal, merciful, truthful trial resulted in a wrong verdict, while the second full of corruption, calumny and perjury, resulted in the truth being set in the noonday sun on a hilltop". Yet objective historians agree that the trial conducted by Cauchon was a judicial murder, while that of 1455-1456 was conducted by sincere churchmen under the authority of the Pope according to Church law in a fair and just manner. Some cynical authors, prior to Shaw, asserted that it was not a fair retrial, because it would have been politically unthinkable for the 'retrial' Court to find Cauchon and the English 'not guilty' and Joan to be a Witch. No doubt the judges in this second trial were aware of the need to phrase their final verdict in a way which would not reopen old wounds, but this does not mean that the findings of the trial were falsified. It would have been politically unthinkable for the Nuremburg War Crimes Trials to have found the Nazi leaders honourable and just men, unjustly attacked by the Allies. But this does not invalidate the findings of that Court. 'Many persons have believed that the trial of rehabilitation was not a fair trial, but this is untrue' ((WSS 130)). (v) 'PROTESTANT' JOAN Shaw claimed that Joan was the first Protestant because she held to her private belief rather than accept the authority of the Church. Although events took place 150 years before the word 'Protestant' came into use, Warwick is made to say that: "He would call Joan's ideas Protestantism" (scene 4). In itself this may be considered an acceptable use of dramatic licence. An author may consider that he has detected the beginnings of a religious movement in history before it develops the cohesion and strength to be given a name. He may need to use such dramatic licence to illustrate his opinion. The important question however is whether Shaw's assertion about Joan was correct. Joan rejected the authority of what was called: 'The Church' as represented by Cauchon and his sham Court ((WSS 107)), but fully accepted the authority of the Church which consisted of that communion of Catholic bishops, priests and laity living in unity with the Pope. Joan repeatedly demanded her legal right to be tried by the Pope ((WS 114)), but Cauchon refused. She also demanded to be tried by the Council of bishops assembling at the time at Basle. Cauchon again refused. Joan attended Mass every day, was frequently at Confession, prayed to the saints and maintained a strict adherence to the moral law. During three months of continuous and very subtle questioning, Cauchon and his well-educated aides were unable to trick her into making one heretical statement. Observers were amazed that an uneducated peasant girl had such a grasp of deep Catholic theology. The official teachings of the Catholic Church are restricted to what Christ revealed explicitly or implicitly while on earth. So a private revelation is not part of the Catholic Faith. When The Church establishes a Tribunal to investigate a claim of this sort, it is in order to protect the faithful from self-deluded individuals and fakers. A tribunal will sometimes accept that a vision is authentic, but belief in the vision does not become part of the Catholic Faith. For example: A Catholic who was not convinced that Christ's mother appeared at Lourdes would not be guilty of heresy. Joan's claim to be receiving visions and hearing 'voices', was not contrary to the Catholic Faith, and there was a long tradition of individuals maintaining that they had received private revelations. Joan was willing to submit her claims to the judgement of the Church. She did this at Poitiers and in her repeated requests to be judged by the Pope or a Church Council. So Joan was a very loyal member of the Catholic Church. Joan was willing however, as all Catholics should be, to defy a bishop when he was acting against Catholic teachings and laws. If anyone at the trial could be said to have acted in a 'Protestant' manner, it was Cauchon. He placed loyalty to the king of England before his loyalty to the principles and laws of the Catholic Church, and refused Joan her right as a Catholic to appeal to the Pope. (vi) MIRACLES Shaw denied the possibility of miraculous events, and took the opportunity of the play to ridicule the idea of such happenings. In a comic atmosphere he shows hens refusing to lay eggs until the commander agrees to send Joan to the Dauphin (Scene 1). But the real reason for the commander being convinced that Joan's demands should be considered seriously, was her ability to inform him correctly of events taking place 200 miles away. At a crucial moment during the relief of Orleans the wind was blowing in the wrong direction for the sailing boats to venture up stream. Joan is shown persuading the army general to wait while she goes to pray. While they are arguing, Shaw indicates the wind direction changing by means of a flag. Joan and the commander do not notice this, so Joan sets off to pray. On her return she finds the wind blowing in the right direction and so thinks that she has worked a miracle (scene 3). In this manner Shaw provokes his audience into laughing at these two superstitious stage characters for believing a miracle had occurred. Yet all the historical evidence points to Joan and the general knowing very well which way the wind was blowing. Whatever one may think about the possibilities of miracles, the incidents did not occur in the manner depicted by Shaw. They persuaded a commander and a hard headed army general, to put their trust In Joan. Shaw does not mention other incidents which were considered by many at the time to be remarkable. (vii) PERPETUAL IMPRISONMENT After Joan put her signature to the paper promising to obey: 'The Church' rather than be burnt, she was returned to her cell. Shaw presents Ladvenu as sentencing Joan to 'perpetual imprisonment'. Joan is depicted as rising in anger, while exclaiming that she would rather be burnt than shut from the light of the sky and the sight of the fields, and then tearing up the paper she had signed (Scene 6). At this she is excommunicated and led out to die. But this in nothing like what happened. Joan was forced to don male attire when her own clothes were removed. It was this alleged disobedience to 'The Church' which was used as an excuse to kill her. If Shaw had included this information in his play, the guilt of Cauchon would have been clearly seen. Joan was sentenced to 'Carcer Perpetuus' and Shaw renders this as 'life-long prison'. But examination of Inquisitorial records show it to mean simply a permanent prison as opposed to a make-shift building which was casually employed for the purpose. As there was the ever-present threat of her being rescued by a French force once she had been transferred from the castle, this was not surprising. There was nothing in the sentence to determine how long she would be kept ((HT406)). (viii) NATIONALISM Shaw presents Joan as the first 'nationalist', but French nationalism was well developed before

Joan's time ((MGAV 17)), as was that of England and Spain. Shaw depicted Joan as fighting for her rights as a woman against the prejudice of a narrow-minded mediaeval Catholic society. Yet, as pointed out earlier in this publication, all France including churchmen, royalty, the aristocracy and the peasants recognised Joan's right to dress as she chose. A Church Tribunal, of greater authority than that established by Cauchon, had already accepted her right to wear male clothes. Shaw showed Joan as a rebel in foregoing the role of a wife and a mother, so as to have an army career. It is true that this was unusual in those days, but it is still so today. She undertook this career with reluctance at the urging of her 'voices'. She was not trying to prove that women were 'equal' to men. As a Catholic Joan knew that, in the eyes of God, men and women were equal in dignity, but she did not encourage other women to become soldiers. Joan treasured her chastity and it was her Christian modesty that made her dress in the only clothes available in her cell, thereby giving her enemy an excuse to kill her. Only in Cauchon's Court and in Shaw's play was 'dress' turned into a supposed teaching of medieval Catholic Faith. (x) THE DAUPHIN The English have never thought highly of Charles VII since he threw them out of nearly all France. Shaw perpetuates this traditional English view of Charles (The Dauphin). He alludes to him as: 'a rat in a corner, except that he won't fight' (Scene 1), acting childishly, of being dominated by his advisors, handing the command of his army to Joan because he was superstitious, doing nothing to save her, being ungrateful and desiring her rehabilitation for selfish reasons. But, as illustrated earlier in this publication, this is a false picture of the real Charles VII. (xi) CONCLUSION REGARDING SHAW'S HISTORY

REFERENCES (Page numbers given in text) AL....... SAINT JOAN by ALAN GARDINER (Penguin) 1986 AR....... ST JOAN OF ARC by A. RYAN (Australian cts) 1984 BS........ SAINT JOAN (THE PLAY) by BERNARD SHAW 1923 CW....... BERNARD SHAW by COLIN WILSON 1969 EB........ BERNARD SHAW by ERIC BENTLEY 1947; 1976 HT....... STUDIES (September 1924) article by H. THURSTON MGAV.. CHARLES VII by M.G.A. VALE 1974 PME..... I AM A DAUGHTER OF THE CHURCH by P. MARIE-EUGENE SS.......... THE MAID by SVEN STOLPE 1956 VSW..... ST JOAN OF ARC by V. SACKVILLE-WEST 1936; 1969 WSS...... JEANNE D'ARC by W.S. SCOTT 1974

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||