|

The ChurchinHistory Information Centre www.churchinhistory.org

Fr. Tiso, Slovakia and Hitler By

The lion finds a frog somewhere. He looks at it from all sides, plays with it, and since the small creature pleases him, he keeps it . . . This is exactly what I think about the Germans. They hold us fast, they play with us, and it has the appearance as if we liked them. And what is now our task and duty? To behave as if we like them, so that they will play longer with us, that they will let us live. For, just as the lion could devour the frog, so the Germans could devour us. It is enough for them to close their jaws and we are done for. And our most noble interest is that we should keep alive. Therefore they may continue to play with is. Our duty, from now on, is to keep them in a good mood." Fr. Tiso at his `trial` in March 1947. A leaflet summary of this booklet is available elsewhere on this web site. ‘CHURCHinHISTORY’ endeavours to make information regarding the involvement of the Church in history more easily available. Part 1 CONTENTS

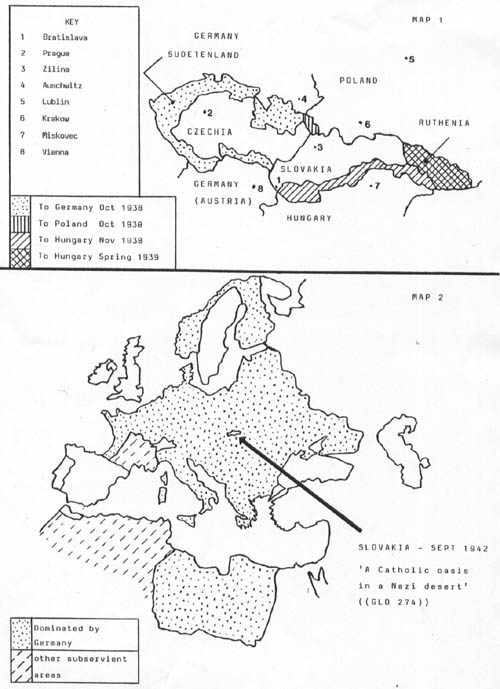

CHAPTER I Slovakia between 1939-1945, under its President Josef Tiso, had a semi-independent existence as part of German dominated Europe. Tiso was not only the President but also a Catholic priest, who often undertook parish work on Sundays. He received wide support from other clergy and from leaders of the Catholic laity. In 1941 this predominantly Catholic country placed itself on the German side in the invasion of the Soviet Union, and in 1942 over 50,000 Slovak Jews were sent to Concentration Camps in Poland. Anti-Catholic political groups and religious sects have used these facts in an attempt to prove that the Catholic Church supported Hitler and therefore shared responsibility for his crimes. Also they often accuse the Vatican of having conspired with the Slovak Catholics before the war to destroy the new democratic, socialist and progressive Czechoslovak state. The Vatican's main strategy being to encourage the Slovak Peoples Party, led by Fr. Tiso and other priests, to demand independence for Slovakia and thereby undermine a united Czechoslovak resistance to Hitler. A balanced and full presentation of the history of that time shows this picture of Fr. Tiso, the Church and the Slovak people are false. Yet, as bias against Fr. Tiso is evident in very many history books, it is necessary to correct it. Following the First World War, Marxist Social Democrats and Communists were strong forces in Czechoslovakia and together with the National Socialists dominated political life. Although the British Labour Movement was not Marxist, many of its 'intellectuals' were, while others took a very left-wing stance. It was these writers and authors who used such words as 'progressive', 'freedom-loving', 'democratic', 'social reformist' to describe the marxists and centralists in Czechoslovakia. At the same time they labelled the Catholic led movements as 'fascist', 'separatist' and 'reactionary'. A comparable group, sympathetic to the Catholic and autonomist interests, did not exist in Britain to correct this one-sided reporting. After the collapse of Czecho-Slovakia in 1939, Socialist politicians fled to Britain and America enabling them to propagate their account of events with ease. The Slovak leaders stayed in their homeland so were not available to refute the accusations made against them. When Slovakia joined in the invasion of the U.S.S.R., it became easy for Communist war-time propaganda to depict all the Slovak leaders as 'fascist'. These political controversies have now faded into the past, but their legacy maintains a lasting influence on the British view of Slovak history. So it is not difficult for anti-Catholic sects and individuals to make accusations, and be able to point to otherwise reputable books for apparent confirmation of their claims. CHAPTER II Prior to the 1914-1918 War, Austria and Hungary were united under the rule of the Hapsburg monarchy. This Austro-Hungarian Empire incorporated Slavonic peoples along its northern and southern borders. During the war the Allies encouraged these races to fight for their independence. The word 'race' is frequently used to denote the various peoples of Eastern Europe, but this can be misleading for modern readers. 'Race' now tends to denote a biological group, but until the rise of eugenic Nazism, it referred more frequently to a language and culture. In 1918 the victorious Allies deposed the Hapsburgs, split Austria and Hungary into separate states, allocated the southern slavs to Yugoslavia and agreed to the northern slavonic peoples — Czechs, Slovaks and Ruthenians — forming a new state of Czecho-Slovakia. For geographical reasons the German speaking Austrians living in the Sudetenland could not remain part of Austria. But as the victors wished to keep Germany as small as possible, these Sudetenlanders were not permitted to be incorporated into Germany. They were therefore included in Czecho-Slovakia. ((See next page, Map 1)).

The Slovaks considered themselves to be a separate nation to the Czechs but, as they numbered less than three million, recognised that complete independence would be difficult to maintain in that turbulent part of Europe. They therefore saw the advantage of joining with the Ruthenians and the more numerous Czechs to form a federal republic ((GLO 180-182)). In 1914 there were 500,000 Slovaks and 300,000 Czechs living in America ((DEM 26)), and they were working hard to obtain freedom for their homelands. They were able to organise away from the chaos of the war zone. In the 'Cleveland Proposal' of October 25th 1915, the Czechs agreed that in any future state the Slovaks would have autonomy ((GLO 162 and AXS 19)). But remarks made later by Czech leaders implied that the Slovak way of life would be submerged in a Czech dominated culture. This attitude was typified by a phrase in a note sent by Masaryk, the Czech leader, to the British 'The Slovaks are Czechs' ((GLO 162)). At a special meeting of priests living in America held on September 20th 1917, it was promised that Catholic Slovakia would be free from Czech anti-Catholic discrimination ((GLO 169)). But many Slovaks were still suspicious that Masaryk was using Slovak money and willingness to volunteer for the Czecho-Slovak legions (army), so as to achieve Czech freedom, but once this was obtained would relegate the Slovaks to a subordinate position ((DEM 6)). So on the 30th May 1918, Masaryk signed on behalf of the Czecho-Slovak National Council, 'the Czecho-Slovak Pact', which became known as the 'Pittsburgh Agreement'. This guaranteed to the Slovaks their own administration, parliament, courts of law and the use of Slovak as the official language of their schools, public offices and public affairs generally ((GLO 175, 203-4, AXS 19, JM 111, JFNB 158, VO 85, DEM 32)). In the same month the Catholic led Slovak Peoples Party, operating in Slovakia, voted to become part of this new evolving state. The smaller Protestant led Slovak National Party echoed this move ((DEM 27)). In October 1918 Masaryk also signed a pact with the Ruthenians promising them autonomy within a federal state. This became known as the 'Philadelphia Agreement'. In October 1918 a provisional Czecho-Slovak government was established in Prague. On November 11th, it expressly recognized as valid and binding: “all Conventions and Engagements concluded or undertaken by Masaryk during the revolutionary period”.((DEM 34,GLO 175)).Slovak autonomy seemed assured. At the Paris Peace Conference Eduard Benes, the Czech leader negotiating on behalf of the provisional government, promised that the new state would very much resemble Switzerland ((DEM 92)). This was a clear commitment to a decentralised Constitution. But while promising that permission would be granted for the wide use of the German language, the Slovak language was ignored ((EW 92-93)). Fr. Hlinka, as leader of the largest Slovak party, planned to attend the Conference and demand the right to hold a plebiscite so that the Slovaks could democratically decide if they wanted autonomy. When the Czech authorities refused to issue him with a passport, he obtained one from the friendly Polish government. But Benes asked the French police to expel him as 'An agent of the Vatican and the Hapsburgs' ((GLO 190)). At the time France had an anti-Catholic government and complied with Benes's request. On returning home Hlinka was imprisoned without trial for six months ((GLO 191)), even though he had legal immunity as a member of Parliament. Hlinka did manage to send two representatives to alert the American Slovaks. But Benes sent a telegram saying they were 'Polish-Magyar Agents' (Magyar being an alternative name for Hungarian. By the time the American Slovaks realized that they had been misled, it was too late to influence the Paris Conference ((GLO 191)). This destroyed Slovak trust in the Czech leaders. So Czecho-Slovakia was granted international recognition without the right of the Slovaks to autonomy being recognized. In this manner the new state was born in an atmosphere of mistrust and bitterness. CHAPTER III THE COMMUNITIES The 1920 census showed the Communities, as defined by language, to be 64% Czechoslovak, 23% German, 6% Magyar, 3% Ruthenian, 1% Jewish, 1% Polish and others 2% ((JFNB 148)). The Slovaks were not allowed to record themselves as such and were entered as 'Czechoslovak'. They formed about 16% of the total population and the Czechs 48%. 75% of the population was nominally Catholic ((DEM 46)), but commitment varied greatly according to racial group. THE CZECHS In the 15th Century an unsuccessful revolt against Austrian rule had become identified with Hussite Protestant beliefs, and during the hundred years prior to 1918, Hussite anti-Hapsburg history was used as a means to stimulate Czech national identity and pride. This spilled over to form an anti-Catholic spirit among the politically conscious ((DEM 47)). By the time independence had been gained, the majority of Czech nationalist leaders were non-Catholic ((DEM 47)), and Thomas Masaryk had left the Catholic Church to become a Protestant ((JM 55)). He rejoiced at the Russian revolution because "A free Russia means the death of a Jesuit Austria" ((JM 93)). Srobar, appointed by Masaryk to rule Slovakia in 1918, had also renounced his church ((GLO 205)). The government unofficially encouraged the Czechoslovak National Church ((DEM 47)), which was formed in 1920. It drew nearly a million Czechs, but few Slovaks, from Catholicism ((GLO 197)). THE GERMANS Although culturally attached to the Catholic way of life, they were affected by that spirit of German Nationalism known as Pan-Germanism, which undermined loyalty to Rome ((EW 228)). Vocations were so few that Czech priests had to be appointed to German speaking parishes ((EW 41)) and the Church was criticised for encouraging 'Czechification' ((EW 228)). THE SLOVAKS In general they were committed to a more religious life-style. Their priests had been closely identified with Slovak history, culture and the striving for Slovak autonomy within Hungary. But he middle classes were influenced by liberal agnosticism, which aimed to exclude Christian values from education and public life. The industrial workers were widely affected by marxist atheism. CHAPTER IV 1. THE CZECH ATTITUDE The Czechs had a strong belief that they were a superior, freethinking and progressive race, while the Slovaks needed to be liberated from their old fashioned religious superstitions ((GLO 214-9)). They considered that the absorption of the Slovaks into the Czech life-style under the cloak of being 'Czechoslovak' (The Czechs omitted the hyphen) would be to the benefit of the Slovaks. There was also an urgent political motive in treating the Slovaks as if they were the same race as the Czechs. If the Slovaks were accepted as a separate nation then the Czechs with 48% of the population would be seen as one minority amongst many. As such they would have to agree to some form of Swiss or federal Constitution, with each community preserving and developing its own culture indefinitely. But if they could rule in the name of 64% of the population, the Germans, Hungarians, Ruthenians and Poles could be treated as small minorities and forcibly absorbed into Czech speech and culture ((RP 15)). 2. THE GOVERNMENT A provisional government ruled from 1918 to 1920. The MPs elected to the Austrian parliament represented the Czechs, but Slovakia and Ruthenia having been ruled by Hungary needed their MPs to be appointed. Masaryk sent Vavro Srobar to choose these MPs. Although 82% of the population was Catholic and the largest party was for autonomy, he appointed 14 Czechs, 30 Protestant Slovaks, 6 anti-autonomy Catholic Slovaks and only 4 pro-autonomy Catholics. So only 4 out of 54 were committed to a Catholic Slovak national revival. It was this 54 strong 'Slovak' delegation that agreed to a centralised national constitution. In 1919 the hyphen was officially omitted from the word Czecho-Slovakia ((AXS 23)). In elections there were 22 parties ((JFNB)) so coalition governments had to be formed. The Social Democrats (marxists) were strong in the Czech areas but also drew support from those Germans, Hungarians and Slovaks who placed 'class' loyalty before their cultural heritage ((GLO 206 and EW 205)). The Communists had a similar distribution of support. The National Socialists, led by Masaryk and Benes, were sometimes referred to as being 'liberal' but although not marxists they took the lead during 1930 in 'demanding nationalisation and central control of industry as well as the planning of trade policy' ((VO 179)). So they could be considered as akin to the British Labour Party of those years. The first elections held in 1920 resulted in a left-wing victory, but in the 1925 elections the Agrarians (Conservatives) became the largest party. But they needed the co-operation of the parties representing the national minorities in order to form a non-socialist coalition government. This administration agreed to establish provincial assemblies ((DEM 54)), but this involved a revision to the Constitution. To amend the Constitution the agreement of the Socialist parties was required. By the time the proposals were passed into law the plan had been severely weakened. 30% of the membership of the Assemblies and their Presidents were to be non-elected appointees of the central government, while the Czech run Civil Service would maintain a tight control over local authorities ((GLO 211)). When the 1929 elections produced a swing back to the centralist 'left', the minorities became increasingly alienated from central government((GLO 221)). 3. THE EXTENT OF ALIENATION The British Minister in Prague reported during the early days of the new state: 'Hostility to the Roman Catholic Church is evinced by Czech soldiers and officials and includes the desecration and mutilation of crucifixes and holy images, interruption of marriages, and similar offences against the principles of culture and decency. The country had been flooded with Czech officials and the Slovaks dismissed, or, if employed, they receive from one-half to two-thirds less pay than the Czechs. Corruption exists in public offices and attempts are being made to substitute the Czech for the Slovak language.' ((FV 17-18 quoting DBFP 1919-39, First Series, Vol. VI, page 335)) In 1924 Seton-Watson, a Czech supporter, admitted that 'Slovakia cannot be expected to tolerate the present system, under which not only the vast majority of the best posts are held by Czechs, but preference still continues to be given to Czechs rather than Slovaks for many entirely subordinate positions, indeed in many cases it is not merely preference, but open favouritism'. ((GLO 201)). Czechs living in Slovakia increased from 7,500 to 121,000 between 1910 and 1930, with most being in government service ((GLO 200)). In central government during 1938 only 33 out of 1246 Foreign Office officials were Slovak ((MSDF 11)). Of 139 army generals, one was a Slovak. ((OB 25)). In defence of their record, the Czechs pointed to the money and personnel deployed to eradicate illiteracy in Slovakia, and expressed indignation at the 'ungrateful' response of the Slovaks. The Czechs were so confident in the superiority of their secular culture that it didn't occur to them that most Slovaks considered their own Christian culture to be the superior one. Novak summed up the situation in 1930: 'Educational Institutions in Slovakia are reeking with Pan-Czechism and are manned throughout by freethinking Czechs. The Slovak language is being swept under the carpet, while the Catholic religion is made an object of ridicule'. ((GLO 215)). The Ruthenians were being treated in a similar manner ((GLO 199)). Although the Ruthenian right to autonomy had been promised at Paris in 1918 and 1919, the Czechs refused to implement it. A Czech military government ruled for 20 years and tuition in the secondary schools was in Czech ((OB 2223)). As for the Hungarians: 'The grievances of the Hungarian minority were real . . . as a peasant population in the main, their problems contrasted sharply with those of the Sudeten Germans, but they were worse off with regard to language rights, and their press was more severely censored'. ((EW 253)). Hopes of the Germans accepting the new state were undermined because: 'in a thousand little ways the Czechs, in the early days of the Republic, set out to humiliate the Germans' ((EW 118)). 4. THE BEGINNING OF DISINTEGRATION Under Hitler, Germany regained its self-confidence and this spirit soon affected the Germans living in Czechoslovakia. In 1935 the party of Konrad Henlein, leader of the alienated Germans, received 62% of the vote in the German speaking Sudetenland ((EW 206)). Their loyalty to the state became extremely doubtful ((EW 277)). In the early days following the war, Czechs could claim that the number of literate Slovaks was not sufficient to fill administrative posts. But in later years, when this was no longer true, the favouritism became more obvious. As it was the new generation of educated young people who were suffering most, the demands for autonomy gained support amongst Slovak youth ((DEM 87)). In 1926, according to Czechoslovak police reports, 40-60% of Slovak students supported the Slovak Peoples Party and by 1936 it had increased its hold considerably ((FV 29)). The Czech centralists became worried and reversed their policies. They promised the Germans an end to discrimination, and permission for a German language radio station ((EW 246, 255 and xi)). The Ruthenians were promised autonomy, and the Hungarians permitted to use their language in their schools and on public buildings in their districts ((EW 253)). Talks were held with the Slovaks but broke down over the basic principle of Slovak nationhood. The Czechs demanded that the Slovak Peoples Party gave unconditional loyalty to the Czechoslovak Republic before the Czechs would decide how much autonomy they would permit, and from past experience the Slovaks feared that this would be extremely little. Although the Slovak Peoples Party supported the idea of Czecho-Slovakia, they maintained their right to proclaim independence if the Czechs refused to keep their promise regarding autonomy. But if the Czechs accepted this principle, the Slovaks would be placed in a very strong bargaining position. A compromise could not be found. On June 5th 1938 a Slovak rally of 100,000 commemorated the twentieth anniversary of the 'Pittsburgh Agreement' ((GLO 222)). Fr. Hlinka, who was still leader of the Slovak Peoples Party, said: "If possible we will remain with the Czechs. Otherwise, we will be forced to direct ourselves in another direction, for we have no intention of living in slavery". He went on "The Slovak people want to live freely, be it even at the cost of the Czecho-Slovak Republic" ((GLO 222-3)). Fr. Tiso said: "We want this Czecho-Slovak Republic to be able to stand up at any international forum knowing that domestically all is equal and proper". He warned that: "unless the Slovaks were satisfied, the Republic could not survive; but when the Slovak has achieved his rights and autonomy, he would defend the Republic" ((DEM 79)). It is necessary to note that while the fight for Slovak autonomy was closely identified with Catholic priests and active lay Catholics, autonomy was not itself a religious issue. Many saw autonomy as a means of ending anti-Catholic discrimination and enabling the promotion of Catholic inspired social reform. But good Catholics also supported other parties. The Agrarians favoured regionalism ((AXS 62)) with Provincial Assemblies and were not philosophically anti-religious. The Czechoslovak Peoples Party, led by Fr. Jan Sramek, was also fighting for Catholic rights and social principles, yet opposed Slovak autonomy ((AXS 54, 59 and 63)). This party elected a Representative from Slovakia in 1925 and again in 1929 ((GLO 209-210)). Protestant autonomists voted for the Slovak National Party led by a Protestant clergyman, Martin Razus ((FV 27)). At a Conference on October 16th 1932, Tiso made his famous statement: "In national politics a Slovak Protestant is closer to us than a Czech Catholic. ((AXS 55)). CHAPTER V Although the government's attitude to the Germans had noticeably improved ((EW 273)), the change had come too late. By 1938, 83% of German MPs were preparing the way for their areas to be united to Germany. On September 17th 1938 Lord Runciman, British mediator, reported to the British Premier 'Twenty years of Czech intolerance and discrimination had driven the Germans to resentment and revolt' ((GLO 233)). Two weeks later Britain, France, Germany and Italy signed the 'Munich agreement' which accepted the right of German speaking areas to join Germany. By October 10th the Sudetenland and other German speaking districts had been occupied by German troops to the cheers of the inhabitants. Poland and Hungary now demanded areas of Slovakia. As Britain, France and the U.S.S.R. were unwilling to intervene and the Czechoslovak government was now weak, many Slovaks hoped Germany would speak on her behalf ((MSDF 8)). Fr. Tiso had become leader of the Slovak Peoples Party after the death of Fr. Hlinka. A few hours after the signing of the 'Munich Agreement', Tiso called a meeting at Zilina of the leaders of eight parties ((AXS 87)). At this meeting, held on October 6th 1938, the parties proclaimed Slovak autonomy. Even the Czechoslovak National Socialists (the party of Masaryk and Benes) supported this move ((GLO 236; DEM 118)). There had been an increasing swing towards the concept of autonomy amongst these parties since the mid-1930s. This was particularly true of the large Agrarian party. ((UK 29)). President Benes had resigned the day previously and the new central government agreed to accept the situation in Slovakia. Fr. Tiso was confirmed by the central government as Prime Minister of Slovakia with full powers, except for foreign affairs, national finance and national defence ((GLO 237)). On October 19th the Czecho-Slovak Foreign Minister arranged a meeting between Slovak and German delegations to discuss the future of the area. Hitler urged the Czechs and Slovaks to co-operate with Germany. During this meeting some of the Slovaks indicated a preference for complete independence, but Tiso said that staying within Czecho-Slovakia was nearest to Slovak hearts ((MSDF 10)). An international conference, presided over by Germany and Italy, met at Vienna. This conference of November 2nd 1938 awarded small areas to Poland and a wide strip of southern Slovakia to Hungary ((JFNB 158)). German influence prevented even greater gains by Hungary ((MSDF 10)). See Map 1. On November 30th 1938 the Slovak Representatives took part in the election of Emil Hacha as President of Czecho-Slovakia and on December 1st the central parliament agreed to permit the President to rule by decree for two years ((KCA 3366)). All elected bodies and organisations were dissolved. In Czech areas democracy ceased and the President ruled absolutely ((JFNB 158)). Up until 1938 the Slovak Peoples Party had received about a third of the vote in Slovakia. As non-Slovaks constituted a third of the population it could be claimed that half the Slovaks were demanding autonomy. In addition, the Agrarians and the Traders Party wanted some form of regional independence ((DEM 87 and AXS 25)). The loss of Polish, Hungarian and German areas made Slovakia more homogeneously Slovak ((DEM 110)), the centralist policies of the left-wing governments had made the regionalist parties more militant and the fast moving events had caused an upsurge of national feeling. The eight parties which had declared autonomy ((FV 33)) now formed the National Unity Party as a means of resisting outside pressures. Although democracy had been suspended in Czecho-Slovakia, the Slovaks exercised their autonomy by asking the people to approve the policies of their political leaders. The National Unity Party alone put forward candidates, the people and press treating the voting as a plebiscite on the issue of autonomy ((LND 19-12-1938)). The Unity candidates received 98.5% of the vote, so some commentators have questioned as to whether 'it was a truly free vote. In judging this, several factors need to be borne in mind. The members of the eight former parties, ranging from fascist to National Socialist (the party of Benes), were urging a 'yes' vote. Although banned, the Communists also now supported autonomy ((YAJ 33)). The marxist Socialists and the Jewish Party, neither in the Unity Party, had drawn their main support from the area which had now been incorporated into Hungary ((AXS 26, YAJ 3, 4 and 20)), so had little support. As the remaining Hungarian minority was now to be permitted their own schools they would have voted 'yes'. The Unity Party nominated 100 candidates for 63 seats so voters had a choice and knew the traditional political views of the personalities standing. The election was conducted according to central government law. A Commission from Prague, which supervised the voting, found it was secret, without pressure, and legal ((LND 19-12-1938)). All the parties that had joined the Unity Party had candidates elected and the national minorities had representation. Although non-Slovak parties and the marxist Socialists were not permitted to contest the elections, the 200,000 Czechs and Jews were free to vote ((KCA 3371)). All the candidates supported autonomy and none advocated complete independence ((DEM 128)). A very significant indication of Tiso's desire for autonomy, not independence, was his statement made at the moment of this triumph of Slovak nationalism. He declared that the voting not only proved the support of the government by the popular vote, but also represented a. plebiscite in favour of the maintenance of Czecho-Slovak unity ((KCA 3371)). On January 18th 1939 the new Slovak Parliament opened in the presence of the central government's Prime Minister. The President of Czecho-Slovakia confirmed Tiso as Premier of Slovakia ((GLO 241)). At this time Ruthenia also gained its autonomy ((GLO 239 and DEM 119)) making Czecho-Slovakia a tripartite federation ((JFNB 158)). CHAPTER VI In early March 1939 discussions regarding finance between Slovakia and the Czech dominated central government reached deadlock. In 1938 the Czechs could do little to prevent Slovak and Ruthenian autonomy, but now they felt more confident and aimed to gain a firm financial grip again ((DEM 132 and See APPENDIX A)). Slovak extremists led by Vojtech Tuka openly called for a declaration of independence before Czech domination was re-imposed ((DEM 132)). In February Hitler decided that it would suit his plans if Slovakia became independent ((GLO 241)), so placed the Vienna radio station at Tuka's disposal ((GLO 241)). The Czechs became worried about Tuka's activities, so on March 10th President Hacha moved Czech troops into the Slovak towns and disarmed Slovak paramilitary Guardists ((AXS 73)). Tiso was dismissed, 200-300 politicians arrested ((MSDF 13)) and Charles Sidor appointed as Prime Minister ((GLO 242 and DEM 133)). The Czechs claimed that Tuka had been poised to seize power and proclaim independence under German protection. The Czech Foreign Minister did not accuse Tiso of having been involved in the plot, but feared that he would have been too weak to have prevented his own overthrow ((DEM 63, 133 and See APPENDIX B)). Sidor was a firm supporter of autonomy but the Czechs considered him to be a stronger personality. Some anti-Catholic publications have stated that when the Czechs deposed Tiso, he had to 'flee' to 'his friend Hitler' for protection and assistance. This assertion has not the slightest basis in fact. He moved to a local monastery before retiring to his parish of Banovce ((FV 39 and AXS 73)). Sir Neville Henderson the British Ambassador to Germany, found the Czech leaders: 'Unbelievably short-sighted and domineering in their treatment of the Slovaks', and he tried to persuade the Czech Minister in Berlin to urge his government to settle its dispute with the Slovaks, and withdraw their troops before it was too late. He warned that it: 'was playing Hitler's game for him and that its folly would end in disaster . . .' ((GLO 242)). Germany expected the Slovaks to offer armed resistance and call for German assistance, but both Tiso and Sidor rejected the offer of German aid. They then took part in talks to form a new government. A group of Germans visited Sidor and threatened in a brutal manner that the Hungarians would be permitted to take the country if independence was not proclaimed. But neither Tiso nor Sidor would take this step ((AXS 73-4)). Sidor was a popular moderate with views very similar to Tiso's, but most Slovaks saw the latter as their true figurehead. So Hitler invited Tiso to meet him in Berlin and threatened that if he refused to come, two divisions of German troops would march in and divide Slovakia between Germany and Hungary ((WS 441)). After gaining the approval of the party Presidium and Sidor's cabinet, Tiso arrived in Berlin on March 13th. Hitler informed him that Germany was about to occupy Czechia and that Hungary was preparing to occupy Slovakia. If however the Slovaks wished to be independent, he would guarantee them against Hungarian threats ((SEE APPENDICES C and D)). Although Hitler couched his demands in a friendly form of words, it was a brutal threat. A reply was required by the following day. Tiso telephoned Sidor asking him to arrange a meeting with President Hacha to summon the Slovak parliament. It assembled the next morning and Tiso explained the choice to the Representatives. The 57 present unanimously chose independence ((GLO 249 and AXS 75)). Before leaving Berlin Tiso had been handed an unsigned telegram addressed to Hitler. Following the vote for independence, Tiso had to sign this telegram and send it to Germany, as part of the price of averting a Hungarian and German invasion. The telegram was published by Germany throughout the world to show that the Slovaks wanted Hitler's assistance and friendship, ((KCA 3484)). This destroyed Tiso's character in the eyes of much of world opinion. But the wording and sentiments were not composed by Tiso ((WS 442)). At his 1947 trial Tiso stated: "If Hitler's pressure had not been there, the Slovak Parliament would never have voted for Slovak independence" ((MSDF 13)). In a public statement designed to explain the position to his people, without provoking Hitler, Tiso said: "In this tense political situation, in which states and peoples are changing their form, it is clear that we can maintain ourselves only by becoming an independent state". ((GLO 249)). On March 14th President Hacha went to see Hitler ((WS 444)). When he, and his foreign minister arrived in Berlin, he was met with full military honours ((KCA 3485)). They were put in the best hotel and Hitler sent Hacha's daughter a personal gift of chocolates ((WS 444)). But later that day in privacy Hitler threatened to bomb Prague unless the Czechs asked to become a 'protectorate' of Germany. Faced with this threat Hacha agreed to 'ask' German troops to occupy Czechia ((WS 447)). Hacha was forced to announce that he had: ' . . . confidently placed the fate of the Czech people and country in the hands of the Fuehrer and the German Reich'. ((WS 447)). Both Hacha and Tiso had acted under duress. The sentiments they had publicly expressed were not their own. British public opinion had been taught that the Czechs, as secular liberals and socialist, were firmly democratic and anti-Nazi, so Hacha's words must be seen as those of an unwilling man. But Tiso had been portrayed as a pro-German fascist, so his words were accepted at face value. In doing so, the myth of Tiso being a fascist was reinforced. Tiso was not pro-German or in any way fooled by them. In the autumn of 1939 he said: "Do not think that the Germans do anything whatsoever for us because of our blue eyes”. ((AXS 87)). CHAPTER VII i) HALF FREE The Constitution of the new state was ratified on July 21st 1939 and Tiso was the obvious choice for President, but he hesitated to accept the post. Pope Pius XII expressed the opinion that it might not be wise for a priest to hold such a high political position ((GLO 26 and AXS 834)), but left the decision to Tiso. It was many years after the war that the Church enacted a law prohibiting priests from holding political offices. Archbishop Kmetko encouraged him to accept, as it would place him in a position to be able to protect the Church and people from Nazism ((GLO 269)). So Tiso agreed to become President. The office was more symbolic than executive with his main power that of being in a position to restrain the government. The Germans claimed that it was necessary to station troops in the country in order to 'protect' it, but the Slovaks refused to sign a treaty legalising this. Although Hitler possessed overwhelming military strength, he was aiming to gain the friendship of other small countries in the area, and this gave the Slovaks some room to bargain ((NR 63)). On August 12th after vigorous arguments a treaty was signed and German troops had to withdraw to a thin strip along the western frontier. ((GLO 258)). No country protested at Slovak independence and she was recognised by nearly every European nation including Britain ((SEE APPENDIX E)), and the Soviet Union ((SEE APPENDIX F)), France, Germany, Italy, Yugoslavia, Rumania, Hungary, The Holy See, Bulgaria, Poland, Lithuania, Finland and Switzerland. China, Japan and countries in South America also established relations. The only major state which held back was the U.S.A. The League of Nations which at that time did not include Germany or Italy, refused to listen to the protests of the Czech exiles. Of the 28 countries affording recognition only ten eventually fought on Germany's side ((GLO 258-263)). Left-Wing commentators described the Slovak State as 'fascist', but this word was being used as a term of abuse rather than an objective statement of fact. For many years between the wars, Communists consistently called the Socialist parties 'social fascists' ((HSW 107)). Tiso, speaking on behalf of his party on August 15th 1937 had said: "Fascism is a centralist trick . . . we are against fascism and dictatorship". (GLO 79)). In 1938 when the Party of National Unity was formed, fascists formed a very small minority. The Slovak struggle for political and cultural rebirth occurred during the same period that Germany and Italy were aroused from despair, lethargy, weakness and lack of self respect. So it is not surprising that a Slovak political speaker such as Tiso might liken the revival of those countries to the similar struggle in Slovakia. But this does not mean that the ideology capturing the imagination and idealism of one country was the same as that inspiring another. In 1938 Winston Churchill issued a statement to the Press in reply to an attack by Hitler. He denied that he and other British politicians were warmongers and continued '. . . I have always said that if Great Britain were defeated in war, I hoped we should find a Hitler to lead us back to our rightful position among the nations, . . . ' ((TT 7 Nov 1938 page 12)). This statement does not prove that Churchill was pro-Nazi, nor do similar statements by Tiso indicate that he favoured Nazi ideology. The Slovak state was established with a full democratic Constitution. Parliament was to be elected by universal secret ballot for five years, with the responsibility of electing the President. Executive power was subject to an independent judiciary, the Constitution protected family life including the right to a family living wage and religious teaching in the schools. Private ownership was recognised but was to be limited by the interests of the common good ((GLO 268)). Tiso said "We intend that industry shall serve the good of the whole nation, not merely its own good. So, you may say that our economic aim is a special type of Socialism based on Christian principles. We know that capital must be allowed to earn a fair return. But we intend that the worker shall have a fair livelihood with security against unemployment and unmerited poverty. The government will interfere in industry only to correct, but not to direct". ((GLO 271)). Cultural liberty was ensured to non-Slovak minorities with rights to their own language, education and parliamentary representation in proportion to their numbers. Due to the exceptional situation all non-Marxist parties had freely united into one party, but the Constitution allowed for the formation of other parties. The various national minorities had representatives within the National Unity Party ((GLO 272)). A Lutheran was put in command of the Slovak army ((AXS 190)). Insurance against old age, sickness and unemployment was extended. At the same time co-operation between employers and employees was encouraged as a means of improving working conditions. It was this rejection of the marxist principle of 'class war' that was labelled as being 'fascist' by Communists and left-wing Socialists. How Slovakia would have developed in a time of peace and complete freedom it is not possible to guess. During most of its existence Slovakia was at the geographic centre of Hitler's empire and surrounded by German and pro-German forces on all sides ((See Map 2)). Within the country the pro-German minority exercised an influence out of all proportion to its size. Slovakia has been described as: ‘A Catholic oasis in a Nazi desert'. ((GLO 274)). Despite these problems, water-power was harnessed for the electrification of industry and the modernisation of agriculture. Large numbers of homes and schools were built, and there was a comfortable and rising standard of living ((GLO 2745)). University students increased from 2,034 in 1938 to 5,432 in 1942 ((GLO 277)). The Czechoslovak government publication: 'The Central European Observer' of June 27th 1949, by which time the Communists were in complete power, admitted that: 'during its six years of independence Slovak economic wealth was strengthened beyond all expectations and ... it is difficult to ask the broad masses to forget that from 1939 to 1944 Slovakia was prosperous in the midst of a warring world'. ((GLO 275)). ii) THE LION, THE FROG AND ERNEST BEVIN During his defence speech, on 17th and 18th March 1947, before the Court in Bratislava, Tiso explained how he had assessed this relationship: "The lion finds a frog somewhere. He looks at it from all sides, plays with it, and since the small creature pleases him, he keeps it . . . This is exactly what I think about the Germans. They hold us fast, they play with us, and it has the appearance as if we liked them. And what is now our task and duty? To behave as if we like them, so that they will play longer with us, that they will let us live. For just as the lion could devour the frog, so the Germans could devour us. It is enough for them to close their jaws and we are done for. And our most noble interest is that we should keep alive. Therefore they may continue to play with us. Our duty, from now on, is to keep them in a good mood." ((JT 40 as recorded in LGN 15)). Any judgement of Tiso's motives and policies must bear this assessment in mind. Mr. Ernest Bevin was the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in the British Labour Government formed at the end of the war. On 27th February 1947 he spoke in the House of Commons regarding the signing of peace treaties with Hungary, Bulgaria, Rumania, Finland and Italy. But his words could also have been applied to Slovakia. "As regards the German satellite states, their position from the time of the outbreak of war was a most unenviable one. Certainly the Balkan satellites were left little choice but to give way under German pressure". ((HPD, 5th Series, vol. 433, House of Commons, page 2290, HMSO 1947)). iii) TISO VERSUS TUKA Vojtech Tuka had spent nine years in prison for his political views, and by 1938 had become bitterly anti-Czech and pro-German. His extremism alienated most Slovaks from him and Tiso didn't trust him ((AXS 85)). He was included in the Unity Government in 1938 and again in early 1939, but was isolated by the rest of the Cabinet. Through German pressure he became Prime Minister on 27th October 1939, but still found himself outmanoeuvred by Tiso and the other Ministers. In early 1940 Tiso received a warning from the Germans that Foreign Minister Durcansky must stop expressing his anti-German attitude ((GLO 281)). Before 1939 Durcansky had worked with the Germans so as to put pressure on the Czechs, but he had no wish to substitute Czech rule with that of Germany ((AXS 85 and WS 437-438)). On June 30th 1940 Tiso, in a speech not pleasing to the Germans, said the Slovaks needed no foreign ideology to supplement their Catholicism ((AXS 85)). Tiso was already unpopular with the Germans because he would not persecute the Jews ((See this Chapter, Section v)), so Tuka took this opportunity to visit Hitler. He asked for Slovakia to be incorporated into Germany with himself to be made President in place of Tiso. Within a few weeks Hitler summoned Tiso and his Ministers to a meeting at Salzburg ((AXS 86)). Hitler intended to put an end to all anti-German attitudes in Slovakia and the Salzburg meeting was a major defeat for Tiso. In order to prevent direct day-to-day intervention in Slovak affairs, Tiso had to dismiss Durcansky and appoint Tuka as Foreign Minister as well as Prime Minister. Sano Mach, a colleague of Tuka, became Minister of the Interior. At the same time a new German representative was sent to Slovakia with the aim of fighting 'Political Catholicism, Jews, Freemasons, Pan-Slavs and the Durcansky clique' ((NR 63)). On his return home Tuka declared: "It doesn't matter to me whether 99% or 1% are with me, I will carry out my aim". Tuka wanted Nazi style National Socialism to be established ((GLO 283)), but had such little support in the country and amongst the rest of the Cabinet that he had no success ((GLO 283)). In early 1941 Tuka prepared to seize complete power, but Tiso rallied his supporters to prevent it ((GLO 283)). Hitler allowed Tiso to remain as President because he was popular with his people. His replacement by the much disliked Tuka would have led to civic unrest at a time when German troops were required elsewhere. At the same time Tiso knew that he would be deposed if he showed open criticism of Hitler. So he gave verbal tribute to Hitler, including expressing gratitude for his help in achieving Slovak independence, in order to eliminate or minimise German interference ((AXS 87)). Tiso's public praises of Hitler were tactical and not made out of any admiration for Hitler or Nazi ideology, which he disliked ((AXS 87)). He explained his policy in his own words: 'They [the Germans] were aware of their superiority and of certain success in case they decided to intervene, for they saw in us a small people and a small state. On the other hand, they considered it unnecessary to intervene in Slovak affairs before these became a serious danger from their point of view. My efforts were directed to confirm their belief for as long as possible, to facilitate the undisturbed and conscious development of Slovakia'. ((LGN 19-20)). Tiso hoped that Germany would not directly intervene in life of Slovakia if he: (1) treated the German minority with justice and granted it broad cultural freedom, (2) banned Communist and any other Marxist pro-Soviet activity and (3) limited Jewish power. By pursuing this policy he was successful in keeping the SS and racism out of Slovakia for six years. He prevented Nazi teachings entering the schools and most of the youth organisations. His policies shielded the nation so that Christian values could be promoted and the Slovaks saved from the deprivations suffered by other peoples. As a Slavonic race these deprivations could have developed into genocide. The price he had to pay was that of making subservient gestures towards Hitler and from time to time uttering words of praise for Germany. It is these words, torn from their historical context, that have been used by enemies of Slovakia and the Catholic Church to blacken Fr. Tiso's name. Tiso's policy was firmly supported by the Slovak Catholic bishops and clergy. Their aim was to protect and promote a Christian anti-Nazi and anti-Communist humane society. ((AXS 90-91)). After the war, Archbishop Kmetko said that he regarded Tiso's regime as a guarantee that Slovaks would not have to fear Nazism ((AXS 92)). iv) FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND THE WAR The Agreement of August 1939, signed when Slovakia 'asked' for German 'protection', included a clause stipulating that Slovak foreign policy must support that of Germany. So Slovakia was not independent in the full sense of the word, but had a degree of internal autonomy within the German Empire. But for Slovaks who had been ruled by the Hungarians for a thousand years and the Czechs for twenty years, this degree of internal independence was a great historic achievement. When Germany and the Soviet Union invaded Poland in 1939, Slovakia assisted the Germans and permanently occupied five small districts. As Poland had seized three of these in 1920 and the other two in March 1938, the Slovaks felt entitled to regain them. Hitler offered further land in the Tatra mountains but being a non-Slovak speaking area it was refused ((MSDF 20 and AXS 82)). In June 1941, at the time Germany invaded the USSR, Tiso was away from his capital city. Tuka, without consulting him, ordered two divisions of the regular army to join the invasion. Tiso declared that the war was not to the benefit of Slovakia, yet admitted that the country had to comply with the agreement signed with Germany ((LGN 20)). In December of the same year, Tuka declared war on Britain and America. But Tiso hurried to point out that no competent state organ had declared war, so officially Slovakia was still at peace with the Western Allies ((LGN 20)). Tiso's attitude to the war against the Soviet Union was more complicated. There were many politicians throughout Europe who supported Hitler when he was victorious but became silent as the tide of war changed. By the closing months of the war they often re-emerged as collaborators of Stalin. Tiso did not follow this path. During the first period he tried to minimise Slovakia's involvement in Hitler's aggressive war against Russia, and in the second period he encouraged his people to oppose the spread of Soviet power. Tiso declared that the Slovak participation in the war was only 'symbolic' ((AXS 117)). Only 20% of the troops mobilised during the First World War were sent to fight ((JMK/MSD)) and by 1943 Tiso had managed to bring them all home. ((JAM 131)). When Hitler demanded a greater contribution of Slovak troops, they were refused ((AXS 94)). Tiso's sadness, at seeing his country as an ally of Germany, was well known. In November 1941 he visited Slovak troops in the Ukraine to see how the people had lived under communism. While visiting the monastery of Pecerskaja Lavra in Kiev, the building was dynamited. Tiso's life was saved because he had left the building a few minutes earlier than planned. This attempt on his life was probably carried out by Himmler's secret police, who always had an inimical attitude to Tiso ((UGD/MSD)). Until 1943 Nazism was the greatest threat to Christian life in Slovakia, but as the Soviet armies advanced westwards, Communism became a greater threat. Also, the Czechoslovak exiles in London made it clear that they would neither consider the Slovaks having independence nor autonomy. For Tiso and the Slovak nationalists the future looked hopeless. So they grasped at straws. Their one hope was that the German generals would overthrow Hitler and ask for peace, If accepted, Soviet troops might halt at the frontiers of the USSR and the Germans return home. This would leave the peoples of Eastern Europe free to decide their own futures. So Tiso encouraged the Slovaks to provide economic assistance to the German defence of eastern Europe while secretly planning to break free from German control if the opportunity arrived. It is during this period that many pro-German and anti-Soviet (or anti-Communist or anti-Bolshevik) statements were made by Tiso. Many of these were directed against internal Communist revolutionaries rather than Stalin's armies. The assertion that such statements showed Tiso to have been a fascist is not based on calm historical analysis but on Communist propaganda. Tiso often assisted anti-fascists. American and French soldiers who had escaped from German prison camps were granted asylum despite German protests ((GLO 277)). Italian and Rumanian diplomats who had deserted their fascist governments were also granted protection in Slovakia ((GLO 277)). Part 2 |